Straight in the Eye

John Haberin New York City

The Shape of Things: The Menschel Collection

The Poetics of Place and the 2017 AIPAD Photography Show

"Whoever looks you straight in the eye is mad." Roland Barthes was describing the power of photography to picture a life fully apart from our own.

For Geoff Dyer, though, the ultimate photograph captures someone who can never look you in the eye. It only seems that the person can, with the eerie stare of the blind. Would he care that an entire exhibition refuses to look back?  MoMA exhibits photos from a major donor, as "The Shape of Things," with the emphasis definitely on things. The Met brings the story up to date with its collection, as "The Poetics of Place." And if those histories of photography are not haphazard enough, there is always the 2017 AIPAD Photography Show.

MoMA exhibits photos from a major donor, as "The Shape of Things," with the emphasis definitely on things. The Met brings the story up to date with its collection, as "The Poetics of Place." And if those histories of photography are not haphazard enough, there is always the 2017 AIPAD Photography Show.

Things to come

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes confesses to his inability to approach photography that pictures anything but lives. For him, it is about the "enthusiastic commitment" to human society, or studium, as revealed in the punctum—a telling object, a passing glance, or a transient moment. It remembers "the people, the entertainments, the books, the clothes." Geoff Dyer might well agree, in The Ongoing Moment, but he finds its ultimate expression in a blind woman as seen by Paul Strand. Photographers keep returning to the blind, he argues, because they are always engaged in the encounter between the camera and its unwitting subject. Walker Evans hid his camera under his coat, because nothing else would allow his subjects to speak for themselves.

Neither Barthes nor Dyer has much patience for photography about anything other than people, as portraits or groups, although even Alfred Eisenstaedt allowed himself Central Park in the snow. Robert B. Menschel sure does, though, in the five hundred photos that he has donated to the Museum of Modern Art—well over a hundred in the last year alone. A selection as "The Shape of Things" has a fondness for photographers out to catalog things in themselves. It includes Jules Janssen, with his sky atlas spanning seventeen years, through 1894. It includes Charles Marville in the 1870s, out to document every design of street lamps in Paris, and Bernd and Hilla Becher with their obsession with water towers one hundred years later. It includes Charles Harry Jones around 1900, with onions too pristine ever to eat.

People are surprisingly hard to come by and never quite themselves. Dora Maar photographs a worker, but with his head lost in a manhole, and Weegee a man cross-dressing—not because he is transgender, but because he cares too much for performing to worry about his authentic self. John Coplans treats his own back as an obstacle or a blank palimpsest, his fists raised above. Robert Frank, like Jane Dickson decades later, turns to Times Square at night, but from a distance and in a blur. An-My Lê photographs the Mojave Desert as a site for combat exercises, with the emphasis on exercises rather the dangers of combat. David Leventhal goes the next step, to toy soldiers for his apparent scene of war.

They still testify to a sexual or cultural context, indirectly or not. Yet they largely avoid documentary or commercial photography, with the allure of politics, portraiture, and fashion. John Gossage sees the city from behind the support for a bridge, its lives cut off by a thick black cross. Hans Bellmer sees sex itself as akin to a mechanical ballet. Harry Callahan seems least at ease with his own wife. William Wegman may come closest to other genres, but with Wegman's dog—posing on a couch after Gustave Courbet or balancing a book on its head like an aspiring model.

The show falls in three sections, but their stated chronology quickly falls apart. "Truthful Representation" begins with William Fox Talbot in 1843, with a street as Pencil of Nature, and ostensibly ends in 1930. "Directorial Modes" turns to the recent past, with truth or representation now in scare quotes. In between come "Personal Expressions," but a photograph from any date can appear anywhere. The collection's heroes fall in the middle section—with decades of blank facades from Callahan, sidewalk smears from Aaron Siskind, and torn posters from Lee Friedlander. The curators, Quentin Bajac with Katerina Stathopoulou, do not hesitate to note the parallel shift in painting from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art.

They supply a history of photography, photography's claim to truth, and photography's last century for all that, although almost without color. Even a still life by Jan Groover appears in black and white, while a glass of water from Neil Winokur is downright shocking in its blue. They also tell a human story after all, but one of the passage of time—like buildings new to Paris in the 1890s, but now as picturesque as can be, or the George Washington Bridge for Berenice Abbott in 1936, when it was still the shock of the new. The show's title derives from paired photos by Carrie Mae Weems of African forts. One has its gate facing front, promising an entry or a haven in the present, while the other stands as mud pillars, like totems from an ancient civilization. Ultimately, the title derives from The Shape of Things to Come, by H. G. Wells, but without its last two words. In a photograph, what was to come is already the past.

Neither poetry nor place

Late in life, Walker Evans returned to Hale County, Alabama, but the sharecroppers had gone. So, after all, had the Great Depression, decades ago at that, and so had the professional camera that captured its most stubborn survivors. This time Evans brought an emblem of a different kind of transience, that of consumer culture—a Polaroid camera. The results even look disposable, and they show temporary housing with no trace of the lives within. In the past, he had also collected penny photos and postcards, but now he saw no need to defer to studio professionals of any sort. To pile on the ironies, the medium to which he turned is obsolete in today's stubbornly digital age as well.

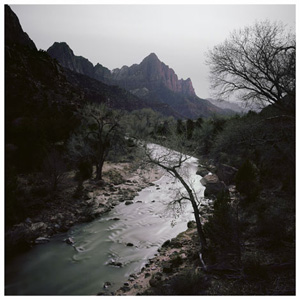

"The Poetics of Place" has precious little poetry and almost as little sense of place. Even when Carrie Mae Weems travels to Mali and An-My Lê to Vietnam, like Evans in search of origins, their destination seems out of reach. For Weems it reduces to a mud dwelling in soft focus and for Lê to the far side of a dense riverbank, and both could just as well be left over from prehistory or the day before. And even when Wolfgang Staehle sticks to the specificity of a single day along the Hudson, his slidecshow of eight thousand images seems oddly detached. In place of the Hudson River School and the American sublime, he has the banality of real time. He also has an artery along which nothing and no one seems to move.

The Met samples recent photos from its collection, but it takes its theme from the 1970s. Minimalism and earthworks had discovered repetition, waste, and entropy, as with Robert Smithson or coal mines for Bernd and Hilla Becher. Photographers still traveled America, like Robert Adams or Dan Graham, but to trailer parks and the cheap housing of Staten Island and New Jersey. They linger on railroad crossings, like Laura Burns and Lother Baumgarten. They track the damage due to industrialization and natural disasters, like California after a flash flood for Joel Sternfeld. Strong colors for William Eggleston and Eggleston's "Los Alamos" only bring out the awkwardness.

The Met samples recent photos from its collection, but it takes its theme from the 1970s. Minimalism and earthworks had discovered repetition, waste, and entropy, as with Robert Smithson or coal mines for Bernd and Hilla Becher. Photographers still traveled America, like Robert Adams or Dan Graham, but to trailer parks and the cheap housing of Staten Island and New Jersey. They linger on railroad crossings, like Laura Burns and Lother Baumgarten. They track the damage due to industrialization and natural disasters, like California after a flash flood for Joel Sternfeld. Strong colors for William Eggleston and Eggleston's "Los Alamos" only bring out the awkwardness.

The Met describes its subjects as landscapes and built environments, leaving open where one ends and the other begins. It notes the role of the New Topographics, in Adams and Lewis Baltz. It invokes, too, the slippery border between amateur and art photography, as with "slow snapshots" for Jean-Marc Bustamante. You may not have known Donald Judd as a photographer. Yet he traveled south of the border to document ancient ruins. They would do his Minimalism proud. They also have eerie affinities with Mexico City sidewalks that, for Damián Ortega, look like tombs.

The show can feel like a throwaway. Most of its fewer than thirty artists have only a work apiece. Some, too, have the unexpected, like Judd. Sally Mann appears not for family portraits but for Virginia in the mists. Jan Groover, known for still lifes in gleaming color, also photographed the "semantics of the highway." Suffice it to say that cars go in irreconcilable directions.

They are not above beauty, like Darren Almond, with his "fifteen-minute moon." They are not above remembering as well, like James Welling, who sees the present through film noir, or Matthew Brandt, who prints the ruins of Madison Square Garden with his darkroom medium its own dust. They may even try to locate a sense of place, like a coffee plantation for Jan Henle—although it looks more like the surface of Mars. Sarah Anne Johnson follows the Arctic Circle, where she photographs herself at her tripod. You may wonder if someone else is behind the camera. You may wonder, too, if she will ever break closer to the pole.

The challenge of photography

You know the challenge of pier 94. You know it from the March art fairs, where the pace is blistering and even the VIP lounge is a madhouse. Big, bright images from instantly recognizable artists assault you from every side, all of it for sale and spilling out onto the adjacent piers as well. And then, after that long journey west of the theater district, competing fairs demand your attention all over town. Well, guess what? If you have any energy left four weeks later, the challenge of the AIPAD Photography Show is that none of this is true.

Photography is bound to be a challenge for a big fair, given a medium that does not often reward a distant view. With its move from the Park Avenue Armory to the Hudson, this fair has expanded to well over a hundred exhibitors, far beyond what will be the 2022 Photography Show, every one of them asking you to get up close, to take your time, and to look around. They include more than two dozen nonmembers of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers, many of them smaller galleries in rows of smaller booths, as "Discoveries." They also include Lucien Samaha, who makes his booth his studio, where those with appointments can sit for portraits with (he swears) the world's first digital camera. They do not pack the pier anywhere near as densely as the Armory Show—all the better to suck you in. They share the pier with a spacious area for publishers and three private collections as well.

For all that, they are notably traditional. They reach back to Gustave Le Gray and the 1850s with Hans P. Kraus and to what another dealer dares to call a history of printing. They include such well-deserved staples as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy with Robert Koch, Man Ray and André Kertész with Contemporary Works/Vintage Works, Margaret Bourke-White with Howard Greenberg, and Robert Frank or Richard Misrach more than once. Contemporary photographers, too, reach back to the Bauhaus or Surrealism—like abstract landscapes with von Lintel, the view down a spiral staircase by Luciano Romano with Sabina Raffaghello, and an interior overlaid with UTOPIA by George Rousse with Sous les Etoiles. Steven Kasher boasts of twenty-one photographers but just one straight white male. That sounds ever so millennial, but it spans the years from Diane Arbus to Mickalene Thomas.

In short, this is photography as art. It includes several dealers that do not specialize in photography (and omits at least two in New York that do), but new media are rare apart from cascading blue pixels by Clifford Ross with Ryan Lee and a projection on the pier's glass entryway outside by Colleen Plumb. So are abstraction and other crossings of genre and media, apart from Niko Luoma with Bryce Wolkowitz. So is anything resembling photojournalism, apart from classics of street photography on film in a "screening room." So, too, is fashion or even portraiture—apart from Samaha and the Walther collection, with photographers who examine people as types, or "Structures of Identity." That surely flatters August Sander, but maybe not Richard Avedon, and both look the better for it.

In their scale alone, many of the photos call attention to themselves as art objects. Ahmet Ertug's library interiors with Ellipsis Projects and Christian Voigt's museum galleries with Unix adopt the large format, sharp focus, and subject of Andreas Gursky and Candida Höfer. Jefferson Hayman with Michael Shapiro goes to the opposite extreme, with small photographs in thick frames like forgotten family treasures. Strictly conceptual art hardly appears, as do overlays of text. I might have glimpsed both in a booth empty but for text high on the wall, but no: its statement that an Iranian dealer had withdrawn in the face of Donald J. Trump's travel ban is all too true.

Elsewhere politics stands at a distinct remove. The Madeleine P. Plonsker collection captures "The Light in Cuban Eyes," but with an eye more to the light than to the regime. The third private collection, from Martin Z. Margulies, presents international artists—but the brute facts of concentration camps, Mideast photography, and the refugee crisis get along peaceably with the allure of the exotic. A fair with few solo shows obliges you to pick your own favorites. They might include towering industrial landscapes by Edward Burtynsky with Koch and, among Discoveries, garage interiors wide open to the light by Mark Lyon or walls as visual collage by Andy Mattern, both with Elizabeth Houston. The challenge comes in slowing down long enough to take them in.

"The Shape of Things" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through May 7, 2017, "The Poetics of Place" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 28, and the AIPAD Photography Show March 30–April 2. Related reviews look at the 2018 Photography Show and the 2022 Photography Show.