Miniature Worlds: Art as Model

John Haberin New York City

Gallery-Going: Art and Craft in 2003

Amid the storm called postmodern criticism, Yve-Alain Bois titled a book Painting as Model. He meant a model as in hard science, as an inquiry into reality. An older generation had sought painting for its visual truth or physical presence. Bois looked largely at modernists, such as Piet Mondrian and Barnett Newman, but he place them in a world driven by theory. "What," he asked (quoting, appropriately enough, still another critic), "does it mean for a painter to think?"

Plenty of shows since then have taken model more literally, like the product of an excruciatingly hard modeling kit. What, they might be asking instead, does it mean for a painter to create? It can get awfully finicky, but like a model airplane, it can also take wings.

Once fine art stood in opposition to craft and commercial arts. These days, it can seem, every artist is emulating that eccentric uncle still trying to finish his house of toothpicks. More and more, artists have turned to craft media or painstaking models. Consider "Art Under the Bridge," Betty Woodman, Danny Goodwin, David Opdyke, Anita Glesta, and James Casebere, to name but a few.

They require a fresh look at some hot and heavy arguments over art versus craft. Note: as a follow-up, I have updated the take on Opdyke and Casebere, thanks to their spring 2007 exhibitions.

Bagging fine art

Every fall, Dumbo holds "Art Under the Bridge"—a cross between open studios, a block party, and a walk in the park. It helps make the unforgiving task of selling oneself as an artist a little less formidable. As for the task of actually discovering new artists, one can always give up and join the party. The food has its limits. Still, as with summer sculpture "Between the Bridges," the view of Manhattan is hard to beat.

In 2002, the weekend had a centerpiece—a thirty-foot-high pillar of bananas. Talk about art as like slipping on a banana peel. This year, toward the fringes, an artist assembled a thousand Twinkies. Talk about art as commercialism. Meanwhile, in the Brooklyn neighborhood's oldest gallery, an artist covered the ceiling with a thousand empty trash bags, all gently waving in the breeze.

On the last day in 2002, the crowd had a feeding frenzy. This year, they must instead have witnessed a meltdown. At least they had trash bags to help to clean up after the mess. Either way, art is getting obsessive. As with those bags, one does not need a weatherman to tell which way the wind blows.

One can cite plenty of precedents—from the workshop tradition to the extraordinary craft of painting in oil. Jan van Eyck, a great historian famously said, was able to "confront us with a reconstruction rather than a mere representation of the visible world." Before Arshile Gorky used paints thinned with turpentine for Abstract Expressionism's most fluid creations, he boasted of his thick surfaces. He dared other artists even to lift his early canvases. Even forty years later, Jay deFeo worked so long on her thickly incrusted oils that it took heavy machinery to extract The Rose, now at the Whitney, from her San Francisco studio.

One can cite plenty of precedents—from the workshop tradition to the extraordinary craft of painting in oil. Jan van Eyck, a great historian famously said, was able to "confront us with a reconstruction rather than a mere representation of the visible world." Before Arshile Gorky used paints thinned with turpentine for Abstract Expressionism's most fluid creations, he boasted of his thick surfaces. He dared other artists even to lift his early canvases. Even forty years later, Jay deFeo worked so long on her thickly incrusted oils that it took heavy machinery to extract The Rose, now at the Whitney, from her San Francisco studio.

However, a turn to craft means more than an extension of tradition. It amounts to a sharp critique of art itself. It serves as a way to fool the eye, as tricky as a house of cards. It serves as a reminder of art's place in market economies. It demands attention for others, including women and non-Western peoples, whose craft never got its due.

Somehow this spring, for instance, I was unable to find a place to mention a lovely show by Betty Woodman. Her large, colored ceramics lie halfway between jars, muses, and figures in a dance. She sometimes sets them along a wall or on a long, narrow platform, with a nod to both displays of pottery and to the friezes of Classical art. Her gallery acknowledges the ambiguity. Protech happily sells them either piece by piece or as installations.

Safety in numbers

Do artists such as Woodman or Arlene Shechet eradicate the distinctions between art and craft, like a photographer working from Barbies, or do they create a whole new fairgrounds for both? Does beauty all fit together now, or is art still jarring? Even those ceramics can easily look too cute and sedate. Let me run by some tinier models this fall, before resuming the dialogue.

It can get tedious very fast. This year alone, I have seen miniature villages of one-inch tall yellow people, a little like rebuilding Iraq with marshmallow peeps. I have seen sculpture carved out of dozens of book, a page at a time. I have seen canvases built up from pinpricks of color. I have also, however, seen some serious provocations.

Danny Goodwin models the supposed private residences of the Bush administration. He trains a camera on each from above, like a spy satellite from an unknown enemy. He projects the images on small monitors and blows them up as hazy photographs, seemingly lost in a suburban summer heat wave. I admire the reference to global intelligence. I like, too, the deception—for one must enter the back room to discover the models and to decipher the images. Still, I hope that Wolfowitz and his cohorts reconstruct something more memorable in the Middle East.

David Opdyke, too, associates intricate models with geopolitical networks. Aboard the carrier U.S.S. Mall, stores serve as towers, and miniature cars rather than fighter planes take up the parking spots. They crossed aircraft carriers with miniature shopping plazas, like the ultimate military industrial complex. More weaponry spins delicately upward into an unlikely roller coaster, untold white tubes make up a map of America as power grid, and a tableau of tiny power lines spins into an airy wire abstraction.

Opdyke is back with scale models in 2007. In fact, he alludes to one of the hoariest kinds, the ship in a bottle. This time he trades a critique of capitalism for the age of Romanticism that gave it birth. His foam and plastic ships, now painted in dark hues and displayed in low light, founder like arctic shipwrecks. Opdyke's display looks a bit too beautiful, but also harder now to dismiss as a joke.

To return to 2003, a warhead plated with corporate logos errs on the side of earnestness. A spinning video, shot through a grid with no particular reference, errs on the side of eye candy. Opdyke still works best when he keeps his sense of humor, so as to maintain the balance between anger and beauty.

After the flood

Anita Glesta apparently has the time to rebuild the Pyramids and then disassemble them for good measure. Pedazos turns a Brooklyn backyard into the remains of a civilization, much as nearby galleries are displacing the Polish and Hispanic communities. Perhaps the reference to Mayan and other lost civilizations leaves displaced residents with a touch more dignity and flair. One walks across the stones, each piece separately cast, toward a broken-down pyramid. At the rear of the site, it brings symmetry and focus to the whole.

I liked the accessibility and interaction with the viewer, more like early Minimalism than the temples of late Modernism now. I thought of Rachel Whiteread and her "negative spaces" cast from familiar objects. Ironically, Glesta takes even art's longing for lost civilizations off its pedestal, just when Whiteread is aspiring to monuments.

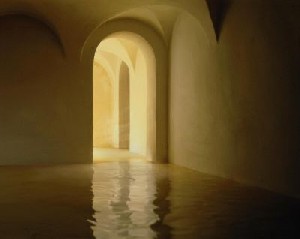

For a greater trick still, James Casebere hides his models entirely. As in an upcoming 2010 Whitney Biennial, his gleaming photos of vacant rooms seem at first simply to make fun of the gallery's white cube. Not a bad start, in fact. Coming closer, one sees signs of ruin. Shadows cascade through darkened abbeys. Rubble courses through a warehouse in Japan, seemingly breaking down a wall. Floods appear to have emptied glorious Italian and Spanish villas of life.

The photographs seem to connect Chelsea at once to contemporary human tragedy and to art history, quite apart from Hurricane Sandy. In reality, they link arts and crafts. Casebere shot not actual rooms but scale models. Ordinary dirt served him for rubble, resin for layers of water. The photographer never left home.

In another 2007 follow-up, Casebere models distant cities, in what his exhibition calls "The Levant." By implication, too, he is modeling all those who look on other cultures with Western eyes. He again photographs cavernous interiors. Palaces, mosques, and amphitheaters gain in drama by their emptiness. Now he adds entire residential neighborhoods, their cheap modern building blocks seen from above at night.

That the old name for the East derives from the rising sun. It adds to the irony along with the mystery that Casebere never looks directly on natural outdoor light.

From allegory to illusion

As before, Casebere plays the illusionist as well as the allegorist. He starts with small models of his own construction, but one would never know it from his photographs' scale and atmosphere. This time I found myself a trifle embarrassed by my own sense of awe. Do I simply know the trick now, or do his plainer cityscapes make it all seem too easy? Last time, too, he imagined halls half submerged in water and other ruins, and perhaps intact structures try harder for majesty. Either way, however, Casebere is smart enough to take myths as his subject while creating his own.

Paradoxically, Casebere's absence of humanity attests to the controlling presence of the modeler. It also serves as a critique of another presence, the gallery as site and as institution, as austere and forbidding as when Marina Abramovic fasted in Casebere's very gallery. Each hint of disaster adds light and texture to the depicted floors. Yet the disaster lives only as image and as model.

What happens, then, to art itself after the flood? When the image fights with the model for power over the imagination, has craft drawn equal to art? Or has craft itself proved one more burdensome illusion? Can there still be an art of the small, where "this one is smaller than this one"?

When, as here, I rediscover old acquaintances and see through their magic, have the artists changed—or have I? Revisiting old ideas is what scientists call modeling. Do artists do exactly that when they find their roots in craft, or do they insist on something less "patriarchal."

The status of the fine arts has become increasingly controversial, and the controversy has proved increasingly valuable. Critics have called the distinction between art and craft without meaning or foundation. They have pointed to values that come with the labels. They have asked who gets to choose both the values and the labels. Fine art may not go away any time soon, but it has much more on its tail.

I can hardly settle the issue. Suppose I eavesdrop, however, on an argument in progress. I, of course, get to claim both sides for myself.

A dialogue of self and soul

— One must not imagine fine art as something to pure to spoil with kitsch, especially now that formalism has passed into history. Art as much as craft always has a social role. Historians today analyze even Renaissance altarpieces for their place within a church and a community.

— That does not make all purposes the same, though. Painting itself has had different functions over centuries. A single work may reflect multiple, even conflicting values. One must distinguish them with care and tease out the conflicts, or else one risks losing sight of the work, its time, and oneself. One can better appreciate then, too, the religious and personal motives that art has been privileged to allow.

— Oh, come on. One must not think of craft alone as subservient to need, while art goes off into the lofty space of the personal and the spiritual. Sane gallery-goers get more and more depressed each day about the art world and the marketplace.

— Think museums are tacky, galleries mind-numbing, and studio visits boring? Try yet another crafts fair. One can still enjoy galleries and hate shopping for Christmas. At least one does not feel pressured to replace paintings every year the way some feel they have to buy a new wardrobe. The gallery media machine pales by comparison to capitalism in high gear. This Web site itself beats some major museum sites hands down, if I do say so myself.

— Maybe one should try another crafts fair. Artists have learned to appreciate the beauty of technique and media, including labor and objects long taken for granted. Think of Woodman, for one.

— Sure, art can appropriate traditional media. In the process, however, changes how the media work, in one's mind as in one's life. Woodman does not offer simply pottery, any more than appropriation art equates to garbage (well, at least not always).

Modes of historicity

— Very clever. Still, does this really amount to celebrating art as impure while denigrating craft for the very same thing? The denigration of craft has a function, too. It belittles whole cultures outside the museum's walls, especially "women's work." No wonder so many women artists have incorporated fabric into art in the last decades, starting perhaps with Sheila Hicks. No wonder the Whitney, hardly known for displays of design, this year showed quilts by Southern black women, while the Brooklyn Museum turns to a Southern black woman in Nellie Mae Rowe.

— Why not remember another side of sexism, too? Otherwise, one risks equating feminism with a celebration of past oppression. As Virginia Woolf said, what if women had always had a room of their own?

— Clever again, but it just goes to show: the whole idea of art has a history. Historians can pin down when artists outgrew the serving class. One can point to when artists turned for inspiration from the Bible to "nature" and then from "nature" to "the inner self." One can see each of these terms as a human construct, not a transcendent reality.

— Fine, but one can make the same point another way: art and craft alike create a ritual quite as much as they expressed one. Those first cave paintings already show expression turning into an act of self-creation. They show a need to do something less utilitarian than make dinner.

A dialogue like this is so difficult to resolve because it places art in a broader, functional context, even when younger artists such as Phoebe Washburn are using model building to parody both nature and function. The Museum of Arts and Design, with a new home, removes craft from its name and mission at its peril. Yet this, in turn, forces one to draw rather than simply abandon distinctions.

Seemingly descriptive terms, like art and craft, keep changing significance—and not only because practices change. The terms also come laden with values and biases that themselves change. That does not necessarily make the terms useless. Rather, it obliges one to note carefully their limits. As a payoff, one can better grasp their possibilities as well.

Cultures can build walls, but the very ground shifts, walls always crumble, and flowers grow out from under them. Critics can tear down walls, but one must still attend to the objects between the walls and not just the Wal-Mart. Terms change unexpectedly, but artists as well as critics (and craftspeople) have the power to drive change—by choosing their past as well as their future. Maybe Bois anticipated craft along with high theory after all. "What the strategic model takes account of," he concludes, "is its mode of historicity."

This year's "Art Under the Bridge" ran from October 19 to 21, 2003. Betty Woodman ran at Max Protech through April 26, 2003, Danny Goodwin at Jack the Pelican through December 22, 2003, David Opdyke at Roebling Hall through December 22, 2003, and with the follow-up through May 26, 2007, Anita Glesta at Black & White through February 2, 2004, and James Casebere at Sean Kelly through December 6, 2003, and with the follow-up through June 23, 2007. The Whitney of American Art offered a small exhibition centered around Jay deFeo's hefty flower through February 29, 2004. Painting as Model, by Yve-Alain Bois, is published by MIT Press (An OCTOBER Book, 1990).