Cracks in the Garden

John Haberin New York City

Mary Simpson and Sarah Sze

Yoko Ono and Andy Goldsworthy

Mary Simpson says that she conceives her paintings and video as separate works. Maybe, but do not even try to view them as anything but a single meditation on the economy of nature. They describe an economy without austerity, enriched by culture and by chance.

The entirety of her Off Hours seems to take place when no one is looking, but it encourages contemplation by holding onto the ephemeral. Her paintings amount to wisps of color spreading across canvas as if on its own. The entrance hall unfolds in real time, in what looks like a two-channel projection, although it, too, consists of separate videos.  They turn out to be a collaboration between nature and performance, much like an entire show focusing on Minimalism and dance. They also parallel an imagined garden from artist materials by Sarah Sze, showing its cracks. And then Andy Goldsworthy and Yoko Ono are back, crawling through the leaves and a riverbed—and just maybe into the light.

They turn out to be a collaboration between nature and performance, much like an entire show focusing on Minimalism and dance. They also parallel an imagined garden from artist materials by Sarah Sze, showing its cracks. And then Andy Goldsworthy and Yoko Ono are back, crawling through the leaves and a riverbed—and just maybe into the light.

If and when

The video on the left from Mary Simpson might take place in a garden or the wild. Bees go about their work, flowers accept them and sunlight, and water ripples in the light. The one on the right looks like a performance on an avant-garde instrument, as hands move across a sounding board and strings. Yet the first, A Feeling of If, required more than one artist, for Jasper Johns has cultivated the property. And the second, 10,000 Things, is only preliminary to the act. Those hands are preparing for a dance by Merce Cunningham and a piano work by John Cage.

Their titles embrace the abundant and the immediate, a world of feelings and of thousands, but also the elusive and the trivial. So, too, do the videos, which linger on the now. Artful cuts enhance the sensation. Simpson's paintings do much the same by their arbitrary designs and dimensions, in one case resting on a table of its own weight. A red wisp spreads across white, and white shapes or lines dart across muted yellow or gray. They resemble Mary Heilmann or Karl Haendel in their Minimalism without fixed geometries or industrial materials, like another preliminary to a dance.

The 1960s and 1970s brought together artists and performers as neighbors, studio mates, and kindred spirits. Donald Judd, for one, collaborated with Tricia Brown and Sol LeWitt with Lucinda Childs and Philip Glass. They are all provocative answers to the title of a provocative exhibition, "Where Sculpture and Dance Meet." Yet the greatest joy and surprise comes from an artist who one might forget has anything to do with high art or formalism. Andy Warhol made his Silver Clouds, or foil balloons, for Cunningham's 1968 Rainforest—as (the gallery notes) "objects in a set that was never fixed." And what could be closer to a definition of improvisation or Minimalism?

Sarah Sze opens with a few sticks and, upstairs, a handful of dust. Of course, the dust is pigment, in an intense blue embedded in chalk, and the wood could be leftovers from a stretcher or a work of art. She calls the result her "Fragment Series," including Remnant Studio, and she is dismantling her studio practice before one's eyes. As with all her work, it carries overtones of excess as well as incompletion, because art has a way of exceeding tidy stories. After all, a remnant is what remains. In her case, the remnants include a pendulum, perhaps to stabilize the art or to orient the viewer, and who is to say where a fragment begins and ends?

Who is to say, too, what is under construction and why? Sze's own cracks appear in Deteriorating Garden, all the more lavish and allusive for rudely deteriorating. It holds a hammock of open threads, a mirror touched by pigment as if by soil and light, and a black cube burst apart as if by bullet fire. They make it difficult to picture the garden that once offered an escape. They are at most fragments of a vision of a world beyond—starting in the gallery and the studio. Then again, that pretty much sums up her art and dance.

Each of these artists works between nature and culture, like Simryn Gill with Floating, Three Accounts. Autumn leaves cut into squares form the basis of wall grids. A table holds shattered stones from upstate New York. The third account leaves the "print" of potatoes in ink on paper, like a natural history of taxonomy and starvation. As with Simpson, nature flirts with Minimalism, with assistance from the artist, before going its own way. Art here is a matter of if and when.

Nature's magic

Who is that up in the branches or lurking in the leaves? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it is Andy Goldsworthy, and he is already off to another of those natural wonders that might almost lie in someone's backyard. He has been crawling through the countryside for forty years now, like a single extended ego trip. He has become slyer about it, though, and more intent on nature's magic.

Goldsworthy takes pride in working with his hands and with things as they are—things that he cannot or must not alter. Yet he sure gets his hands dirty. In one early work he emerges on all fours, covered from head to toe in mud, like a figure from a primitive race that ought to have vanished long ago. A room to the side holds a photographic record of work from the 1970s and 1980s, looking all the starker in black and white. Now he comes clean, but his feats have multiplied. The rest of the gallery has still more videos and photos in time sequence, all from the last few years.

Goldsworthy takes pride in working with his hands and with things as they are—things that he cannot or must not alter. Yet he sure gets his hands dirty. In one early work he emerges on all fours, covered from head to toe in mud, like a figure from a primitive race that ought to have vanished long ago. A room to the side holds a photographic record of work from the 1970s and 1980s, looking all the starker in black and white. Now he comes clean, but his feats have multiplied. The rest of the gallery has still more videos and photos in time sequence, all from the last few years.

More than ever, Goldsworthy puts the emphasis on process, while blurring the distinction between natural processes and art. Works like these identify him with nature while making nature his own. He has always worked between earthworks and performance, but he is becoming more openly a performer. When he throws sticks into the sky, he could be returning them to their place in the landscape and to the wind—or he could be in the middle of a juggling act. When thistles form an imperfect sphere in front of his face, he could be inhaling them or exhaling them, as part of a magic act.

The sequence of still photos is ambiguous, but I would put my money on exhaling. He wants to breathe life into nature itself. No, he was never really taking things as they are, much as he trashed this very gallery in 2007 in order to identify it with the great outdoors. With his wall at Storm King Art Center or in walks across the United Kingdom, he is the one assigning a local habitation and a name. In the show's title work, Leaning into the Wind, his silhouette assumes an improbable angle over four frames without evident change, but do not count on their outcome. In context, even that early mud-man looks like a character in a comic book, and I do not mean Superman.

Goldsworthy was always pretentious, like any male presenting himself as primitive man. When Robert Smithson ran along his Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake and Agnes Denes planted a wheat field in Manhattan, they took delight in what they had made, but also in its growing or vanishing beneath their feet. Some part of their energy was necessarily lost to time. Goldsworthy wants control for all his protestations otherwise, although his latest comes closer to accepting entropy. The universe runs in only one direction, like the sticks destined to return to earth only after they have flown apart and away.

The new work displays more obvious physical virtuosity than before, from an artist who turns sixty in 2016, but also more of a sense of humor. Maybe he is inhaling the thistles after all, and maybe he will choke. The videos also invite the viewer into the game, like a treasure hunt. One learns in no time to focus on that pile of fallen leaves, where he is sure to pop up—and then those leaves will no longer be as they were. One accepts the need for patience with his high jinks in order to discover him at work. He may move only slightly, up in a tree or beneath a waterfall, but he wants you to see him coming into the light.

Three easy pieces

The rough circle of stones was almost perfect—and the bare outline of a stone circle all the more so, in a second gallery two blocks away. I wanted to feel their texture and their firmness. I wanted to count the speckles in their mottled gray. And then I read the words to accompany Stone Piece, and I drew away. They serve Yoko Ono as a subtitle, a command, an invitation, and a part of the work: "choose a stone and hold it until all your anger and sadness have been let go." I don't have that long, and neither if she truly knew me does she.

But I wanted to, and despite myself I left just a little less angry and a little less sad. Ono's work is like that—a little silly, a little sentimental, and way too easy, but also playful and open-ended. Line Piece has its own absurd command and invitation: "take me to the farthest place in our planet by extending the line." Yet people do their best, doodling in the sketchbooks laid out neatly on small white tables. They also borrow the black cushions intended for doodlers, turning an entire gallery into a yoga studio without a discipline or a dogma.

The stones are one of three works in "The Riverbed," and Ono speaks of the river as the border or passage between life and death. Well, O.K., but the stones do derive their polish from an actual river, and their placement by the wall recasts an actual room. So does an elastic string, running almost invisibly from wall to wall. One has to duck under or lift it to get from one work to the next. I hesitated, but then I had to enjoy breaking the rule not to step past a line or to touch the art. What starts as the dry abstraction of conceptual art becomes in time more visual, visceral, and communal.

It might be too much to call it subtle, especially with the same three works in either gallery. Ono can seem caught in a time warp, in spirit as well as practice, much of her retrospective a few months before. Almost everything at MoMA dated back a good forty years, to a decade of dissent, and her third work in Chelsea recreates, not for the first time, an installation from 1966. Mend Piece shifts the action to the next room, for broken cups and saucers on a shared table. Yet it has a disarming way of translating postmodern assaults on the "originality of the avant-garde" into collective action. The installations also differ from gallery to gallery, along with the walls, inviting one to look more closely at small differences.

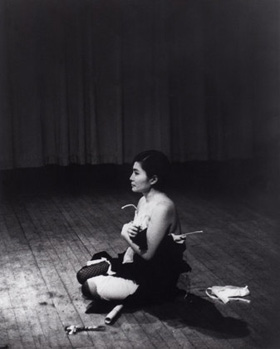

Ono's performance art was always site specific and ephemeral. When she invited people to snip away at her black dress, for Cut Piece in 1964, she took fewer risks than Chris Burden, who suffered actual cuts in crawling on broken glass. It left her progressively naked but as impassive as ever. Yet she dispensed with Burden's macho gesture, in favor of ordinary human vulnerability. She also shared the performance with the cutters. In Chelsea, she yields the stage entirely.

Not that it has become any less crowded. Strangers come together noisily for Mend Piece, like a kindergarten class for collectors, choosing their fragments and their mending aids from Elmer's glue to Scotch tape. Wall shelves fill quickly with the awkward results. One can take secret pleasure in knowing a Japanese tradition of skilled menders, who felt obliged to leave the cracks showing. One can smile at the contrast between the comedy and Ono's instructions to "mend with wisdom" and "mend with love." One can just as well set aside whether "it will mend the earth at the same time."

Mary Simpson ran at Rachel Uffner through December 20, 2015, "Where Sculpture and Dance Meet" at Loretta Howard through November 7, Sarah Sze at Tanya Bonakdar through October 17, and Andy Goldsworthy at Galerie Lelong through December 5. Simryn Gill ran at Tracy Williams, Ltd., through January 10, 2016, Yoko Ono at Andrea Rosen through January 23 and at Galerie Lelong through January 29. Related reviews look at earlier work by Andy Goldsworthy and a retrospective of Yoko Ono.