Inside Out and Outside In

John Haberin New York City

Robert Smithson and Floating Island

Robert Smithson makes a discomforting subject for a museum retrospective. He worked most effectively outside museums, with the earth itself, and he reveled in the artist as outsider to fine-art tradition. Even when he appeared to create sculpture indoors, he was scattering remnants of the outdoors and marking off a "nonsite" with salt and mirrors. Most of all, a retrospective freezes a career in time, and no other artist so celebrated his surrender to the unfolding processes of art and nature.

Fortunately, one bit of his 2005 retrospective escapes the museum—and, in a sense, even the course of the artist's life. For two late September weekends, Floating Island, a work unrealized in Smithson's lifetime, circles Lower Manhattan. I shall argue that the project and indeed his career embody a surprising ambivalence toward the past. Where others associated with earthworks and Minimalism confront, enable, or depend crucially on the viewer's perceptions, Smithson retains a traditional sense of the artist as a commanding, transforming presence. And while he himself insisted on human acts as inseparable from the natural world, he returns to a Romantic opposition between nature's past and humanity's fallen presence.

Smithson rejects Modernism and returns to an older model, but with a twist. That twist arises from a shift not in the terms, but in their valuation: he embraces both geologic time and the fall. It takes a retrospective this unruly to follow the turns. Indoors one can see Smithson the systematizer, with Floating Island his relationship to the American landscape.

Looking backward

A museum retrospective surely gets off on a bad foot, but not because Smithson prefers the earth alone to art. Sadly, his idealism helped lead to installations that trash the gallery for a profit. Yet human acts and human creations, he believed, belong to nature, too, rather like Central Park itself. In a quirky paean to "Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape," Smithson quotes approvingly from the park's creator. Even subways, Olmsted felt, can "enlarge, not lessen, the opportunities of escape." A museum, however, is another matter.

In 1973, as Smithson wrote, the Met was tunneling further into the park, and protests were rising. The museum expansion had marred the park's edge with graffiti-covered gray walls and what he calls a "towering orange derrick." It made him think again of Olmsted's warning, that "the reservoirs and the museum are not a part of the Park proper: they are deductions from it." He might have despised for its sanctimony the ceremonial planting in Central Park of the trees of Floating Island. I could imagine him preferring to bury the assembled parks commissioners and museum officials in sludge, along with the entire aura of a restored ecosystem, with perhaps a moral for art and commerce decades before Hurricane Sandy.

As for a retrospective, it seems a refusal of everything that Smithson attempted. It collects material in one place, whereas Smithson dispersed it. It assumes the museum-goer as a privileged viewer. Smithson might have regretted that his most famous work, Spiral Jetty, quickly sank out of view into the Great Salt Lake, or he might have cared little. The jetty sinks, while the island floats, but he would have marveled at the process just the same.

Besides, a retrospective means literally a looking backward. It denies the arrow of time, what science quantifies as entropy and one of the artist's favorite words. He hated the elitism that he saw, rightly or wrongly, in modernist literature—its horror at the terrifying mess of real life. Still, perhaps he would have heeded James Joyce's update of the sirens, the barmaids in Ulysses: "he's killed looking back."

Then again, he might have treated his Whitney retrospective as one more displacement and one more contribution to the entropic city, like the "building cuts" of Gordon Matta-Clark that he clearly influenced. He might have reveled, too, in its coming to an appointed end. And on the Hudson River piers, as a small crowd sought out shade, strong coffee, and a first glimpse of Floating Island, past and present kept drifting in and out of view.

Could a work that Smithson never lived to see stand as his most representative creation? Could a moving object that never touches land best exemplify his earthworks? If not, what could? Certainly not the early religious paintings in his retrospective, at once half-baked and serving to place his artistic impulses on a pedestal. Perhaps not even Spiral Jetty, so uncharacteristically beautiful and a subject for painting by Eleanor Ray to this day. So what about a ninety-foot barge and the red tugboat easing it around Manhattan?

From entropy to luxury

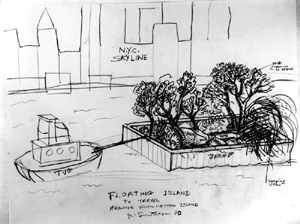

It certainly sounds unlikely. For one thing, Smithson left little more than a 1970 sketch and a few notes. He floated the idea, so to speak, just when Mierle Laderman Ukeles was working with garbage scows, but it went nowhere—ironically enough, not long before New York first rejected The Gates. Smithson would not have liked the incursion by Christo, Jeanne-Claude, and a few thousand tourists onto his cherished Central Park, but no one can know for certain whether he would have felt fully at home with Floating Island either. Would he have liked art that freezes an ideal for thirty-five years?

Floating Island never quite follows his conception anyway. Between the huge problems of navigating the rocky northern waters and the practical aim of pleasing a museum audience, the barge does not fully circle Manhattan. It shuffles around the southern tip, between Ward's Island and, for two Sundays, as far north as central Harlem. One has to track down a tentative schedule at unannounced points in Hudson River Park or online, from a seriously swamped URL. Having tried to catch it three more times since the press preview and having failed, I have come to think of it as subject to a kind of esthetic uncertainty principle: the work exists only when one is not looking.

Just as atypically for Smithson, after his death in 1973 it necessarily became a collaboration. It has survived this long mostly in the head of Nancy Holt, his wife, and its realization depends on her memories and Holt's own land art. No doubt Smithson always collaborated—with the heavy equipment that helped bury a woodshed at Kent State, with Holt, and naturally with entropy and time. Still, few artists have so dominated group efforts. In films of his earthworks, he and the work must count as costars. One remembers most his delight in following the turns of Spiral Jetty, his joy at transforming public spaces into a kind of private playground.

Then, too, Floating Island exists only thanks to a retrospective. An artist who started in Passaic, New Jersey, and died in Texas finally gets to make earth art in New York. It has production support from Minetta Brook, a nonprofit arts foundation that is also helping the High Line further transform the West Village and Chelsea into a serenely gentrified art world.

One could feel the incongruity as Holt introduced the work, on a pier off Charles Street. She recalled herself and Smithson as young artists, living nearby. I could remember myself and artist friends after college, walking West Street at night, on the mournful site of the former West Side Highway, in search of an image of liberty. Now I could watch Holt framed by the most elegant stretch of Hudson River Park, thanks in no small part to the wealthy West Village nearby. Behind us all loomed three Richard Meier luxury apartment towers, the most sought-after addresses in New York. I had read about the trendy restaurant at their base just the other day.

"My own experience," Smithson wrote, "is that the best sites for 'earth art' are sites that have been disrupted by industry, reckless urbanization, or nature's own devastation." What could he have made of piers so extravagantly rescued from decay, with hardly a wreck or a skyscraper in sight—unless one counts the dark slab of Mount Sinai Hospital, far uptown, by the meadow where the first of the trees from Floating Island will come to earth? When I arrived half an hour before, the Hudson looked calm, open, beautiful, and eerily free of art, with the promised work nowhere in sight. The first ship to pass was a luxury cruise liner.

Totality and system

As I tried to grasp what I could not yet see, I thought back to Smithson's retrospective indoors and to the system builder behind it all. When the great outdoors first entered the art gallery, as with Merrill Wagner in fencing and stone, he had already supplied the theoretical justification for an entire generation. Many of his fellow artists almost surely distrusted the compliment. Consider as a contrast another artist associated with earthworks, Walter de Maria and his New York Earth Room.

One could call them a study in opposites. The Californian, de Maria, landed in New York, started his own gallery, and exhibited in "Primary Structures," the legendary 1966 show that helped put both Frank Stella and Minimalism on the map—although Frank Stella had already had six years of stunning work and an appearance at MoMA. Smithson, from northern New Jersey, had his own primary structures, but he seemed to work everywhere and nowhere as well, a paradox dear to his own view of the landscape. He offered a guided tour of the swamps, while Holt trudged after him, recording on film the barely changing scenery and her own shadow. He buried that woodshed in twenty truckloads of earth, and he planned project after project, using dump trucks and steam shovels to deliver everything from mud flows to his most memorable achievement, Spiral Jetty. In contrast, de Maria has only scorn for easterners who fly out west for the week and tell America how to configure itself.

He also approaches earthworks as a totalizer, like Michelle Stuart and unlike Bill Bollinger with his own carpeting of dirt. The Earth Room recalls the ideal garden city of Le Corbusier, only stripped of its greenery. Smithson instead plays the systematizer, and his system has no room for totalities, much as Jannis Kounellis allows cactus to grow in a gallery. His career itself remains forever fragmentary. He died in a plane crash in 1973, at age 35, while working on his Amarillo Ramp. After a career of bringing art to earth, he ended it with that final image of a slope reaching incompletely toward the sky.

Smithson favors any polarity that breaks up the totality. He offers reflections, his pluralizing twist on art as the mirror of nature. If that metaphor once helped to ratify single-point perspective as natural, Smithson pairs triangular mirrored boxes, so that the illusion of endless corridors diverges to either side. One calls these boxes Enantiomorphic Chambers, after molecular and crystal structures that differ only as mirror images of one another. No doubt he found something meaningful in the chemist's vocabulary for these, optical isomers, as purely or impurely visual as art. Another article sought "the crystal land," and his most visually compelling museum installation places mirrors at regular intervals across a field of dirt and rock salt.

As with his chambers, crystals, and earth, he equates natural and unnatural structures. In the same breath, he cites geological eras and moments of discovery, continents and construction sites, as equally brief histories of time. Where early Modernism sees a city in its subways and tenements, his writing delights in the caverns of Sixth Avenue skyscrapers. Where Modernism or the Earth Room reaches back to a pristine landscape, Smithson takes his childhood home in Passaic as a paradigm. He would have appreciated the plot of Being John Malkovich—from breaking the modernist grid with floor 7½ to getting dumped in the New Jersey Meadowlands.

One word, of course, sums up his preoccupation with repetition, degradation, and the arrow of time: entropy. Where Smithson calls in the heavy machinery, de Maria gets his hands dirty, and his art takes pride in that. However, he also has every sign of change pruned from his Earth Room and every visitor chased away from his desert cities, at gunpoint if need be. When Smithson floods a hill with mud or buries a woodshed—"partially," of course—he sees it as accelerating entropy.

Monuments, new and old

Smithson loved schema, sketches, diagrams, and graph paper, and his retrospective is full of them. One "provisional theory," which appeared the same year as de Maria's first roomful of dirt, makes indoor earthworks the missing piece in a simple puzzle. Artists make sculpture and encounter nature. They may alter the site with outdoor monuments, a kind of "non-sculpture." Now, as the missing pole in art's compass, they can displace the gallery with a nonsite.

Again de Maria must consider any resemblance purely, even fiendishly coincidental. He floods the gallery knee-deep with dirt and sensations, to an extent that displaces even the viewer. Smithson instead promised the interior as simultaneously a trace and negation of the site, an absence—what one article called "void thoughts on museums." Conversely, de Maria provides a timeless stand-in for the entire planet. Smithson's nonsites point to specific moments in a cultural and geologic history of the American landscape.

Again de Maria must consider any resemblance purely, even fiendishly coincidental. He floods the gallery knee-deep with dirt and sensations, to an extent that displaces even the viewer. Smithson instead promised the interior as simultaneously a trace and negation of the site, an absence—what one article called "void thoughts on museums." Conversely, de Maria provides a timeless stand-in for the entire planet. Smithson's nonsites point to specific moments in a cultural and geologic history of the American landscape.

For a typical nonsite, he fashions a series of low, metal containers, more faceless and industrial than anything that David Smith, Donald Judd, or even Andrea Zittel today could ever have suggested. He might arrange them to form a triangle on the gallery floor, like a pointer redirecting the surrounding void. Then he fills them with stones from New Jersey and elsewhere, favoring sites that human development is already reducing to scars and rubble. Finally, like David Smith himself, he names the work after the actual place.

A scientist is unlikely to recognize entropy, a concept that involves random variation and the inefficiency of turning energy into work, in the chilly uniformity of Sixth Avenue—or at least no more than anywhere else. Marxism or Postmodernism is unlikely to recognize real history and actual human needs in all the paeans to suburbia. Smithson never gets over a starry Romanticism of his own. He studies at the Art Students League, where William Merritt Chase once held sway, and starts with religious art on such themes as John the Baptist in the wilderness. He makes floor and wall pieces that one passes like old-fashioned sculpture after all, and he praises Judd's "new monuments." In fact, while Minimalism is quickly decaying into the official language of grieving, Judd, Carl Andre, and others, even de Maria, were making far from monumental art—art that stays close to the ground, encompasses the viewer, and reshapes one's environment, mentally and physically.

Smithson's quirky vocabulary, deliberately clumsy sculpture, short life, and uncompleted plans definitely dare a retrospective to keep up, and they often elude even the Whitney. They also make his short life and far-reaching influence imposing for someone like me, who discovered Soho and Artforum in the late 1970s. I remember the connection between system and absence, mark and erasure, in other thinkers of his time, such as Jacques Derrida. I remember Thomas Pynchon's own mantra of entropy. I sense how projects have gained in resonance over time, from the buried woodshed now inseparable from the student deaths at Kent State to the unpredictable rise and fall into invisibility of Spiral Jetty. I want to admire the offhand sketches and drab wall boxes more, I thought again down by the piers, than I ever can—and then, suddenly, there was the alternative to the museum, a real earthwork floating into view.

Just before Holt spoke, the barge of Floating Island puttered toward us, right on cue. I tried to associate the sight with what I knew—its fifty tons of grass and soil, its three three-ton rocks, and its eighteen tons of hay chosen as filler light enough not to sink the project before it began. As it turned briefly toward land, I imagined its ramming the pier and vanishing entirely, entropy triumphing over Smithson's own retrospective. Maybe history could repeat itself, as Marx put it, the second time as farce, and maybe art prefers it that way. The Whitney quotes the artist as identifying the fourth dimension with laughter. Who needs even entropy when one can displace time as well as space?

Remote viewing

As I nurtured the incongruity, I could think of the ways in which Floating Island truly does stand for Smithson's career. The official ways, the ones that he could have articulated, are the easy part. Things grow more difficult and more interesting as one tries to square them with the present. Perhaps an island oriented to an island is itself destabilizing—what Derrida called the "logic of the supplement," the addition that dissolves an apparently closed, unified whole. Consider, then, how this island alters the landscape of Smithson's retrospective.

Smithson valued the picturesque, I shall argue, especially what Cyprien Gaillard deems its post-industrial version, but with a marked indifference to a work's appearance. He created iconic images, but he left them largely inaccessible. He wanted each work to displace an actual landscape, but each creates and preserves an idealized past. He insists on humanity as part of nature's processes, but his images of human intervention identify civilization with the fallen, quite as much as his early religious paintings. Like Ed Atkins in and out of digital art, he asks art to accept entropy, but he leaves his personal imprint on every detail. These paradoxes, it will turn out, make him less the fabled spokesperson for his generation, but more relevant again now, in art's sticky, entropic, cynical present.

Start with the picturesque. In his essay on Olmsted, he revives that Romantic conception, as equal parts beauty and terror. He opposes the picturesque and the sublime to Modernism's preference for the ordinary, the lyrical, and the abstract. He might well also be opposing European formalism to America's mythic self-image, a people as vast and dynamic as the unconquerable land. Smithson's nostalgia seems remote from the Jackson Pollock and Abstract Expressionist more down-to-earth sublime, constructed by hand on the floor of Pollock's shed. It seems more remote still from the chill mappings of landscape and loss in art and science today.

Yet he hardly dwells on appearances. His retrospective consists of innumerable false starts, and art critics—such as Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker—have slammed it for containing exactly one compelling artifact, the film of Spiral Jetty. Smithson is not making hypothetical art or puzzles about indiscernible objects, mind you, nothing like the works that so intrigue Arthur C. Danto. Rather, he accepts gross visual differences and treats them with casual disdain. Floating Island could pass for an afterthought to traffic on the revived Hudson River and the late-summer lushness of Hudson River Park. One can count its ten trees on one's fingers, but they look even more modest in profile out on the water, and one may never notice the grass.

Once the artificial island's trees rest in every New Yorker's backyard, anyone can go see them, but few will notice them. Yet in his own lifetime Smithson left objects that stick in the mind, while he does not make them easy to see. Spiral Jetty may have emerged again at last in 2002, but only when it feels up to the occasion, and the Great Salt Lake has not grown more accessible either. Danto reports making the pilgrimage twice without ever catching the work. Similarly, Floating Island passes offshore, but one must fight hard for so much as a glance, and boarding remains out of the question. As part of its landscaping, the island contains a pedestrian path, but one that no viewer can tread.

Smithson's displacements point toward a larger landscape, but they also idealize it—perhaps because he pictures it in geologic time. His essay on Olmsted starts by imagining New York a million years before, covered in ice. That glacier's slow motion scarred the nine tons of Manhattan schist incorporated in Floating Island. Taking the long view, the barge omits the most common tree in Central Park now. Not long before Smithson wrote, Robert Moses introduced plane trees as cost effective, and the invasive species colonized everything in its path, like a reflection of Moses's urban empire. To make things worse, Smithson asked that the barge contain local species, but the only tree he specifies by name is not native to the region.

Nature, culture, and then some

Conversely, when Smithson opposes the lyrical or the abstract, he decries a landscape too pure for humankind or a vision of art too pure for nature. He argues that "the farmer's, miner's, or artist's treatment of the land depends on how aware he is of himself as nature; after all, sex isn't all a series of rapes." Still, he cannot help seeing human activity as industrial degradation and that "reckless urbanization." He offers his wry odes to the "monuments of Passaic" and to Sixth Avenue, and Floating Island similarly preserves the symbolic opposition between nature's growth and a fallen culture. Again, however, Smithson presents a striking revaluation of these terms, in that he praises both halves of the bargain, the emergent and the fallen. The barge's all-natural contents contrast strikingly with its uniformly rusted exterior—or the cheery red tugboat that may or may not count as part of the work—but Smithson has room for both.

Finally, Smithson takes entropy as his watchword, but also as his personal myth. No wonder he often identifies it more with a faceless, late-modern architecture than with chance patterns, more with New Jersey's endlessly proliferating highways than with the sky above or the land they tore away. With Floating Island, he actually fails to accommodate change. He invents a landscape on which the trees can never take root. That leaves the challenge of ensuring adequate support for the vegetation in high winds and sufficient drainage to withstand even two weekends. Should I ever manage another viewing, after failing on a Saturday from my rooftop and twice on a Sunday from Stuyvesant Cove along the East River, I shall let you know if the team succeeded.

Smithson attained a great influence in a short life. That has to do partly with his art, partly with his essays, and partly with his prescience in articulating a generational shift. Critics have described Minimalism and its time as the culmination of Modernism or as its breakdown. One can see, on the one hand, as deductive logic and monumentalism or, on the other, the introduction of theater in place of formalism and dispersal of attention in place of the privileged art work. Smithson stands closer to the postmodern view, even if the artists whom he praised might not fully agree. However, he does so, in no small part, by looking back to a premodern ideal of the American landscape, the kind that anti-urbanists such as Rebecca Solnit evoke to this day.

He may serve as the last peculiarly American artist, before Postmodernism's international art fair. Floating Island may or may not fulfill his intentions, but at least it preserves his spirited contradictions. A mammoth institutional collaboration, it still drifts in and out of view despite one's best intentions, and it holds onto his systematic opposition between nature and culture, while showing his admiration for the connections and disconnections between both. In no other work did he bridge his two streams of earthwork and nonsite. The barge exists outdoors, but not in a real landscape. It has displaced Manhattan's earth and vegetation into the river, and it will end with the planting of its ten trees in Central Park the week of October 3, starting with the ceremonial planting of a beech tree in the park's East Meadow. A Monday morning ritual makes a natural conclusion to two weekends of island leisure.

By weaving in so many media, including video of his earthworks and a brand new one, the Whitney makes the best possible case. Above all, the film of Spiral Jetty still grips me with its thirty-minute progression from brutality to beauty. It travels from impressive close-ups of heavy machinery depositing earth and stone to sunlight playing off the water, as natural as William Lamson or Izima Kaoru capturing the passage of the sun. Like a retrospective in miniature, it leaves one with the iconic figure of the artist himself, following the jetty, delighting in its emergent geometry. And then there is Floating Island, the ultimate non-Earth Room.

The backdrop of its launch, against a wall of gentrification, may make it his most up-to-date work of all. An artist who yearned for a more perfect intermingling of people and nature finally makes art in a societal context. There is nature and culture, and then there is New York. I can imagine a version of Floating Island that really does circle Manhattan, visible to all ethnic and economic conclaves. In my version, a luxury high rise will appear in the time it takes to complete a circuit, with the grass, trees, and rocks its private garden. That may sound like an impossible schedule, but I know this entropic city can pull it off.

A postscript: floating and boating

When it comes to art torn from visions of Central Park, competition this year has truly been fierce. Yes, coming out of the gate, or maybe The Gates, Christo and Jeanne-Claude took an early lead. But wait: Floating Island leads, as you can now see, by a nose.

As a critic, I could offer to call the race, but I do not even know the finish line. My thanks to Ian Adelman, the Brooklyn design consultant who kindly supplied the photos of an actual incursion on art. The Times confirms the stunt in an interview with Bob Henry, captain of the tugboat, but the two-man gated community has not come forward to claim credit—a sure sign that neither is an artist.

The Whitney takes considerable pride in calling Floating Island the "anti-Gates," as if its sheer visual clumsiness equates to populism. Both works began as proposals decades ago, both still belong to the great age of earth art, both reflect an artist's abiding love of Central Park, and both came to realization only this year. Yet The Gates had a costliness, scale and duration, show-business flair, and artist star quality that may seem more at home in today's gallery scene than Smithson's casual bravura. One could even consider his caviler attitude to finishing the work as truer simultaneously to a genuine avant-garde and grass-roots hopes for art's future, like a musician working on home computer in a garage.

As I discovered in writing about each, that opposition simplifies the impulses behind both. One should not put down Christo's effacement of the boundary's between spectacle and collaboration, including the participation of a team of volunteers and of the viewer as well. Conversely, Smithson's Postmodernism has room for a Romantic view of nature and of himself as the artist at center stage. When I read that hundreds rather than Christo's tens of thousands came to the water's edge, I do not know whom to consider the winner.  Perhaps one should learn, in different ways, from both works that art can have less to do with competition than another day in Chelsea implies.

Perhaps one should learn, in different ways, from both works that art can have less to do with competition than another day in Chelsea implies.

As for the mystery duo behind the floating gate, they seem equally contemptuous of both. "All public art is dumb," said one to Adelman. "The Gates were dumb," the island is "less dumb," and presumably his own version is less dumberer. In fact, I almost want to agree. I want to accept that public art violates everything I expect for a definition of fine art—and a good thing, too. Notice that, while both artists might boast of the work's intimate relationship to Manhattan, you get a view of the Brooklyn waterfront, where the real action is.

Now if only the Whitney could return the island's earth and trees to northern New Jersey, in true homage to Robert Smithson's origins and to entropy. The ceremonial tree planting instead made me think of Earth Day, whereas his environmental ideal and environmental art had more to do with salt, rock, the human imprint, and decay than with an ecosystem's organic growth and sense of repose. Perhaps it could donate the retrospective's mirrors to the fashion industry and the salt to Banks Violette.

"Floating Island" makes eight partial circuits of Manhattan on September 17, 18, 24, and 25, 2005, as part of the Robert Smithson retrospective at The Whitney Museum of American Art through October 23. The James Cohan gallery represents the Smithson estate. My postscript and newspaper coverage of the stunt appeared on the project's second and final weekend.