Facing His Limits

John Haberin New York City

"I love you," "I rejoice," "I suffer" have been said been said and felt many billions of times, and never twice the same.

— Thornton Wilder

Mel Bochner and Andy Freeberg

"The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." Could Mel Bochner be feeling his limits, in a moving retrospective at the Jewish Museum, or has he broadened his world? As a postscript, Andy Freeberg uses text paintings to probe the limits of the art world—or at least its fairs. Yet once again Bochner has the last word.

The limits of my language

The quote is from Ludwig Wittgenstein, in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. One can almost think of its enigmatic prose not as philosophy, but as word painting. Bochner simply adds the paint. Back in the late 1960s, at a time when he was also exploring conceptual art and Minimalism, the artist wrote his columns of words on graph paper, although never all that neatly. He did not use stencils, and his text did not all but vanish like conceptual art, but it proved only the beginning.

He has always, though, been pushing at the limits. In 1970, Bochner created Theory of Boundaries, a wall painting for the Jewish Museum consisting of just four red squares—growing messier from left to right before dissolving into a fiery outline. An accompanying text spoke of "the reciprocity of enclosure and enclosed . . . (disclosed)," as rigorous and as elusive as philosophy. At the same museum now, words have taken on a lot less reticence. Right at the lobby admissions desk, Blah Blah Blah wraps around two walls, its presence heightened by a ground of deep black and blue. The curators, Norman L. Kleeblatt with Stephen Brown, call a retrospective of his text art alone "Strong Language."

At the time of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein still privileged a language of facts and logic, rather than the slippery language of everyday use, with all its questions and imperatives. Yet he already felt an almost Zen-like imperative not to analyze things to death, but rather to make peace with existence. For him, the business of philosophy was not to solve problems, but rather to dissolve them. As he ended the book, "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Bochner could be quoting him with a column of words from 2002, as always in block capitals, beginning with unnamable and unsayable. But then the synonyms descend to unpredictable, unfinishable, and unendurable.

This artist does not have much patience with silence, and he does not expect a casual release from brute or brutal experience. Even language can be like butting one's head against a wall. As he put it in 1970, with paint dripping down from a black square, Language Is Not Transparent. A Theory of Photography draws its theories from all over the map, from Marcel Proust to Marcel Duchamp and from Wittgenstein to Chairman Mao, and it opens with a single word, misunderstandings. Forty years and the Internet have not exactly furthered understanding. His anger at online anti-Semitism prompted a 2008 painting of synonyms for Jew, few of them neutral or pleasant, and then a compilation of terms from The Joys of Yiddish.

This side of Bochner's art might seem too much of a piece, and the seventy works do go by rather quickly. At most, one might think, he has grown better at challenging the eye. The quotes about photography return in 2011, but now seemingly pinned to the wall as trompe l'oeil in soft grays and softer colors. Blah Blah Blah has run through an impressive range of textures and colors, slipping away into the ground while getting truly in your face. Still, Bochner can claim at least one breakthrough, with his discovery of Roget's Thesaurus. With his usual reticence about his boldest gestures, he treats the book as a "readymade," like Duchamp's bicycle wheel but with words as its vehicle.

And it did embolden him, in 2001, with a lively series that riffs on (among other things) nothing, crazy, and useless. He is talking about you, kid—or is he? No question but his art is confrontational, while his strategy of appropriation keeps him at a certain remove. One could say the same about the very first readymades, in the years of bitter disillusionment in and around World War I. It would be a mistake, though, to accuse his art of being above it all. It all comes down to his limits.

The limits of my world

For one thing, Bochner is not just hectoring—not when a series from 2011 includes amazing along with no, liar, and obsolete. Language for him is tempting, chastening, and exhilarating, much like the philosopher's aphorisms. If he has started worrying more about paint on canvas, that comes with the temptations. At his most dour, in 2011, he turns his experience with the Web into the nastiness of :( and $#!+. Yet even here he tempers black on white with the illusion of cast shadows that one would never see on-screen. For him, there are always other voices behind the icons or the words.

For another thing, he came of age in a decade of limits. Born in 1940, Bochner contributed a catalog essay to the Jewish Museum's "Primary Structures," its defining show of Minimalism, as well as an essay on Dan Flavin, "Less Is Less" in 1966. He wrote of the "artist as critic," a phrase that could apply to his text art as well. He also used synonyms well before his supposed encounter with Roget, for portraits of fellow artists that same year, and they are loving portraits. They apply silent to Ad Reinhardt, secrete to Eva Hesse, repetition to Robert Smithson, objectivity to Donald Judd, closure to Sol Lewitt, and wave/particle duality to Flavin. When drawings use circles and arrows, perhaps on their way to a composition, they recall Reinhardt's cartoons of the art world—and anticipate William Powhida today.

Most of all, kid, this is not just about you. Bochner directs his skepticism first and foremost at himself. How can Blah Blah Blah tumbling into blarney and bunk not be about him, after so many years dedicated to words? He has a two-column Self-Portrait as early as 1966, that self sliding into ego and that portrait into caricature. When he paints Silence!, Be Quiet!, and Shut Up! with all their exclamation points, he is again wondering at how much and how little he has said. When he chooses an inky blue for his monochromes, he is surely wondering, too, how much his newfound freedom has outgrown those first words on paper after all.

Of course, this is all about something else as well—about language and its limits. Oddly enough, that distinguishes Bochner from others better known for text art. Unlike for Lawrence Weiner, his near contemporary, text does not just open possibilities for work yet to be made but enumerates them, and it does not describe itself but is itself. Unlike for Robert Indiana or Barbara Bloom, it comes not out of high or low culture, but out of the artist's head or a reference book. Unlike for Barbara Kruger or Jenny Holzer and Holzer's crawl screens, it does not editorialize. Unlike for Richard Prince or Christopher Wool, it does not treat itself or you as a bad joke.

Text here points in two directions, toward an idea and toward a visual sensation. As in a recent group show, "Drawing Time," it moves between the dimension of time, in speech, and of space, in the art object. Yet it also abstracts away from the context of successive words in speech to the context of alternatives, in a thesaurus. And that points to the tricky notion of synonymy. Surely words that mean the same are indistinguishable, but surely then again they are not, which adds depth and nuance to Bochner's portraits. Those two dimensions also correspond to the dimensions of late Modernism, of painterly detail and of bare quotation, as with pretend Brillo boxes.

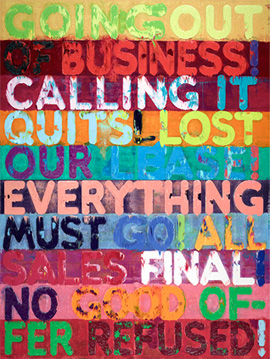

Between nuance and synonymy, he navigates the twin demands to look and to think. Still, can words be exhausted? For a Jew who also knows the joys of Yiddish, is the English language itself an act of self-creation, self-disclosure, or self-negation? Is there a personal meaning in the crusty textures of Going Out of Business? What is left after so much Blah Blah Blah? Perhaps an artist in his seventies is feeling the limits of his world.

Fair to meddling

These are not mere everyday art fans, and this is not an everyday encounter with a work of art. Two men, seen from behind, lean toward each other and a painting, their bowed heads neatly framed by its black square. Their dark suits have further echoes in taller paintings to either side. Where does one find art like this, and where is art such serious business? At the art fairs, of course, that bane of art's existence where a late painting by Ad Reinhardt goes for a lot more than a dime a dozen, even when not curated by James Turrell. Andy Freeberg makes it his business, too.

Freeberg may not capture the color latent in Reinhardt's black paintings, but art fairs do get people thinking in black and white. And his photographs do convey the aura of fine art in upscale surroundings, from the shadows and symmetry of the Reinhardts to the bare walls on which they rest and the hard-wood floors below. It becomes literal in the lights of a booth at Miami Basel—empty but for a table, chairs, and packages not yet unwrapped. Freeberg cares more, though, about the people. He serves up loaded parallels between them and the art, from Miami and the Armory Show in 2010 and 2011. Now that an art fair seems always about to open somewhere around the globe, this may be the new everyday after all, and he is out to bring it down to size.

Freeberg may not capture the color latent in Reinhardt's black paintings, but art fairs do get people thinking in black and white. And his photographs do convey the aura of fine art in upscale surroundings, from the shadows and symmetry of the Reinhardts to the bare walls on which they rest and the hard-wood floors below. It becomes literal in the lights of a booth at Miami Basel—empty but for a table, chairs, and packages not yet unwrapped. Freeberg cares more, though, about the people. He serves up loaded parallels between them and the art, from Miami and the Armory Show in 2010 and 2011. Now that an art fair seems always about to open somewhere around the globe, this may be the new everyday after all, and he is out to bring it down to size.

Staffers hanging pictures extend their bodies to the point of helplessness, while a brash enamel by Joyce Pensato glowers up. They set to work as archly and intently as Zachari Logan's bearded nudes. A man buries his head in his hands beneath the ghetto cool of Kehinde Wiley and Wiley's public sculpture, but then art is a sad affair. (Freeberg's titles identify the dealers, in case one wishes to assign blame.) Mostly, though, people here ignore art and you the usual way, by turning instead to laptops, tablets, and cell phones. Apparently the art notices, and it is not pleased.

Art can exemplify their rapture, like the radiating colors of Piotr Ulanski, or put it to shame. A young man might have ripped his blankness right out of Yayoi Kusama—and his pink shirt out of a canvas by Mark Grotjahn. Warm swirls by Wolfgang Tillmans accompany a woman on a fancy sofa who manages two devices at once. Another woman keeps her composure better than Cindy Sherman, while dressing up almost as carefully. A third borrows her royal and expressive bearing from Elizabeth Peyton to one side, but a text painting by Mel Bochner to the other spells out her instant message: Blah, Blah, Blah.

Get it? Surely you do, for these are clever one-liners, but still one-liners. The whole idea of those under a certain age too wrapped up in texting is a cliché. You can flatter yourself that you would staff a booth for long hours by giving every spare minute to deeper contemplation, but probably you, too, have a life. Besides, these guys are working. Art fairs are way too costly to treat them as private education, and art is way too important to treat it as a lesson in good taste. If you want a real takeaway or two from market pressures and perpetual fairs, start there.

Could Freeberg be complicit in the business more than he knows? One-liners move fast, much like fair-goers. Who knows which aspires more to "slow art"? These are, though, classy one-liners—too classy, in fact, for their purported politics. The work at hand looks great, in large, glossy color prints. Just do not be surprised if you see them at the next fair. And blah, blah, blah.

Mel Bochner ran at the Jewish Museum through September 21, 2014, Andy Freeberg at Andrea Meislin through August 8.