Approaching Poetry

John Haberin New York City

Oil and Water: Painting, Calligraphy, and Poetry

Wang Jianwei and V. S. Gaitonde

A lovely thing about summer, even for those who miss art, is fewer exhibitions and more time to read. And a lovely thing about two summer group shows is how their contributors share the making of both pictures and words.

Can painting approach poetry? In traditional Chinese art, it had to, for they along with calligraphy were the "three perfections." And for the three Chinese and Chinese American artists in "Oil and Water," art once again crosses landscape and calligraphy. The notion of an artist's book seems like mere illustration by comparison.  Still, Western art and poetry have other resources, and so does contemporary Asian art. The five artists and five poets in "This Music Crept By Me upon the Waters" start with a line from Shakespeare, but then they encounter one another in the present—while Wang Jianwei and V. S. Gaitonde address the passage of art in time.

Still, Western art and poetry have other resources, and so does contemporary Asian art. The five artists and five poets in "This Music Crept By Me upon the Waters" start with a line from Shakespeare, but then they encounter one another in the present—while Wang Jianwei and V. S. Gaitonde address the passage of art in time.

A fluid tradition

Is Eastern art all about patience, in the enduring practices of copying and Chinese calligraphy, and Western art all about impatience with the past, in the avant-garde? If you think so, Zhang Hongtu might ask you to consider two visionaries, some three hundred years and two continents apart. His 2004 tribute in oil borrows its towering landscape from Shi Tao (a name that means, appropriately enough, "Stone Wave"), its impasto colors from Vincent van Gogh, and its turbulence from both—but with a zest all his own. Three years later, he had advanced as far as blue mountains out of Paul Cézanne. He will not, however, let go of Asia, and neither will "Oil and Water: Reinterpreting Ink." The Museum of Chinese in America brings Zhang together with Qiu Deshu and Wei Jia, three contemporary Chinese-American artists with a restless eye on Eastern and Western art.

For all three artists, media are not always what they appear. The exhibition sounds rooted in the fluid brush of centuries ago, until one notices that its title mentions three different liquids. For Zhang, an inscription or seal shares space with plain vertical bands and a stormy seascape in oil, out of Romanticism or Modernism. For Qiu, ink on paper may be just the first step in a process of folding and transfer to canvas. Wei Jia may look closest to all-over abstraction, where pink may mingle with yellow and a tan gray. Yet his ink and gouache takes its form from letters, up close as if under a microscope.

All three have been at it since well before an Asia Society Triennial—and well before Asian art found another cross-cultural influence, in comic books, and all have a complex personal relationship to China as well. Zhang, born in 1943 to a Muslim family, moved from Beijing to America in 1982, taking part in an Overseas Artists Association with Ai Weiwei in New York. Qiu, born in 1948, is still based in Shanghai, while struggling in and outside of the official arts organizations. Wei Jia, born in 1957, took his MFA in America but has since lived and taught in Beijing as well. The curator, Michelle Y. Loh, has also organized "Tales of Two Cities," meaning New York and Beijing, to multiply the correspondences between cultures, Wei Jia there paired with Joan Snyder. After his gorgeous single letter in shades of white alone, Robert Ryman or Robert Rauschenberg might have joined him as well.

Loh speaks of uniting the "three perfections" of calligraphy, poetry, and painting—long sought as revelations of an individual's spirit as well as tradition. And in fact Wei Jia first emulated calligraphy before studying western realism. In his return to a kind of poetry, in bold characters on fragments of fine Chinese paper, he abstracts firmly away from its sense as well as from traditional styles. For Qiu, too, paper and collage provide as much of the layering as color, in what he calls fissuring—in Chinese, a word with overtones of both splitting and change. With another nod to older philosophies, he titles a series from the early 1980s Objectivity, Instincts, Consciousness. He also considers an image a "self-portrait," while slipping in a thin body and a childlike head out of Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut.

Qiu and Zhang share a fascination with landscape, but not a land untouched by urbanization. For Qiu, clouds float on a black sea or sky, like icebergs. Elsewhere, he takes what looks like a geologic rift from his observation of cracks in the ground while walking in the city, and a similar patterning on four sheets is continuous across the breaks. In Zhang's most recent work, from 2013, faceless high-rises hover over cliffs, mists, and dead trees disturbingly like the cones of a nuclear reactor. If they both see mostly tall peaks and dark oceans, the very term for landscape, shan shui, means mountain water. Zhang also calls his most western landscape, from 2008, Remake of Ma Yuan's Water Album (780 Years Later).

Art since Modernism has had a spiky relationship to the past. (Appropriation anyone?) The very idea of contemporary Chinese art as "reinterpreting" its ancestors in Asian art (what a later show calls its "Mirror Image") is hardly new, as with a recent exhibition at the Met, and Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook in Thailand has even set Jeff Koons inside a temple. This is also a small show, even with an accordion book by Qiu and documentary video. Yet it does its job, because the slipperiness between places and generations has a mirror in the fluid pairings between artists. It allows them to function together while retaining their dual identity.

Full fathom five

"This Music Crept By Me upon the Waters" does not simply look backward, for its poetry unfolds entirely in New York. Five artists get to choose their poet, with the goal of collaboration rather than illustration. They work in prints often close to carvings, to collage, or to brushed pigment. They move freely between nature, popular culture, and personal memories. They also extend one's expectations for both poetry and an artist's book. Yet they, too, begin with writing from the past.

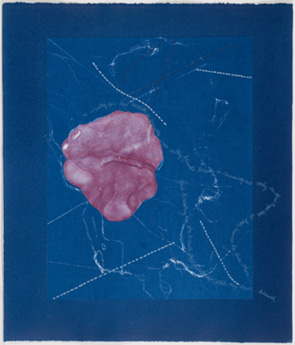

With art sounding the depths (plus Ming Fay's stark figurative sculpture out front), one might think of Shakespeare's "Full Fathom Five," and the show takes its title from The Tempest, where Ariel's song of a father's death recalls King Ferdinand to life. T. S. Eliot quotes those same words in "The Waste Land." In each case, the otherworldly spirit is lying, for life goes on. Nene Humphrey, for one, has grappled with loss by casting her spell upon the waters.  She recorded her husband's breathing before his death in 2006, and in response Tom Sleigh wrote "Recording." Her central shapes, in violet against blue, and her white tracery swell outward like jellyfish with the currents and the air.

She recorded her husband's breathing before his death in 2006, and in response Tom Sleigh wrote "Recording." Her central shapes, in violet against blue, and her white tracery swell outward like jellyfish with the currents and the air.

Words here bubble up beneath the surface. Jane South has has a decided bluntness, in wood and laser-cut museum board. Yet her tabs spin out like master keys to a mystery. Show through —, one reads, and Miles Champion's words often show right through. New owners can rearrange them to their liking, relishing the tactile sensation. The poem is "Providence," and who is to say whether meanings arise by fate or by chance?

Looking for sentence structure or resolution? For most people, living poets are an acquired taste, and Campbell McGrath is terser still. His poem is also somewhere between cultural background noise and signage, as part his "American Noise" collection. And then Stephen Powers reduces it further, to Ice Cold to Go, with a six-pack at their center. His frosted letters do not add all that much to the familiarity of Pop Art, but then they do not try for more. One can almost taste them.

Ken Buhler sticks closest to an artist's book. For him and Cecily Parks, it is also a natural history. They choose upbeat bird names, like Resplendent Quetzel and Superb Lyrebird, and then they start riffing. The pages allow separate areas for images and words, but also ample white space that sets off their density. Where Humphrey settles into blue depths, Buhler pumps up the colors of a pond's or garden's surface. One might be seeing the birds or their habitat.

Where Buhler treats a book as fine art, Dianne Kornberg prefers the graphic novel to the illuminated manuscript. Yet her lettering is as artful as her pearly blackness, flesh tones, flame-like thighs, and upturned legs crossed by stars. It also gives particular attention to Celia Bland's words, in speech balloons and a bottom border. "The sap dripping along his thigh slow as the unconscious delineation of justice and error. A fine dust collects." Whoever "she" is, it is a good bet that The Education of the Virgin will not leave her a virgin.

Eastern standard time

When Wang Jianwei speaks of his work at the Guggenheim as a "Time Temple," it sounds terribly profound. It begs for the timelessness of religious truth and the mystery of being in time, as two aspects of eternity. But what exactly does it mean? Wang speaks only of the "predicament of time," much as Louise Despont appeals to the East for "pure potential," but what predicament? Is it the loss of its passage in the present or the uncertainty of the present moment? Along with V. S. Gaitonde and Danh Vo after Vietnam, he suggests art desperate to step outside of time.

Wang's work alone might have come from three different artists—or three stages of a career. The bulk of it is sculpture, seemingly of sharply hewn wood, although the artist works with more malleable materials. Some of its angled planes add up pedestals or tables, like furniture custom-made by Ursula von Rydingsvard. Others line a tunnel that none may enter, like that of Monika Sosnowska in steel but closer to craft traditions. An orange and yellow abstraction might offer a clue—or not. And then a larger painting stops time once and for all.

It seems to show a ruling party meeting, but with uncertainties of its own. Who is speaking, and who is seated apart, his head bowed at right? One can count twenty-four men around the long table, but no: the several panels repeat Wang's actors at the edges. Its bloodless style, the grays touched by parallel streaks of sunlight, might derive from Minimalism or party propaganda. The show, though, like "Tales of Our Time" to come, was commissioned by the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, under the eye of Thomas J. Berghuis.

At the risk of trusting to time, let me note that Wang was born in 1958 and is based in Beijing. He studied painting but earned his reputation in moving images—first a documentary of rural and urban society, then pageantry and performance with a nod to Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps Godard's Brechtian displacement unites his painting and sculpture, their elements staggered in time and space. Perhaps, too, though, they attest to the difficulty in China of speaking out in the present. One cannot comment directly, but only look for recourse to Modernism and Socialist Realism. One can only hope for a momentary escape from time.

Both tower galleries showcase Asian artists, and both make an accomplished but tepid impression. "Painting as Process, Painting as Life" promises another approach to art and time, and it claims mastery of Asian and western traditions for Gaitonde. Born in 1924, the Indian artist was in debt to Paul Klee as late as the 1950s, much as Mrinalini Mukherjee confronted Modernism with Indian tradition. He was cautious, too, in showcasing Klee's figurative side above his affinities for architecture and abstraction. Gaitonde did turn next to abstraction, though, again both cautiously and beautifully. Black traces break the horizon, against smoky fields of almost bare canvas.

In his last decade before his death in 2001, Gaitonde became more process oriented, like an another Indian artist, Nasreen Mohamedi, or Indian photography in the hands of Raghubir Singh and Gauri Gill. He worked over newsprint and peeled it away, leaving variations on a single rich color. The act leaves behind an image, but also its absence. It often evokes a Buddha—and the curators, Sandhini Poddar with Amara Antilla, note Gaitonde's interest in Zen. Both small shows achieve quiet, scale, and mastery. And both may leave you wondering whether you have seen all this before, with greater challenges to art and the imagination.

"Oil and Water: Reinterpreting Ink" ran at the Museum of Chinese in America through September 14, 2014, "Tales of Two Cities" at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut through August 31, and "This Music Crept By Me upon the Waters" at Lesley Heller through July 12. Wang Jianwei ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through February 16, 2015, V. S. Gaitonde through February 11. A related article looks at Chinese art since 1989.