New Media as Festival

John Haberin New York City

New York Electronic Arts Festival and Daniel Canogar

Mika Rottenberg, Jennifer Steinkamp, and Pipilotti Rist

For a moment I could have stumbled onto a wedding—or at the very least a performance. In the stone chapel on Governors Island, a narrow aisle was lined with lights. At the end a young woman faced the altar, her head veiled in white. The light spread beneath her like a gown. But no, the white on her head was more like a ski cap, its loose knit connected to a sausage-like blimp above. And her trail was just lights from the platform below.

New media had become larger than life, and the New York Electronic Arts Festival was not alone. From the name alone, it sounds like an awkward hybrid between art, music, and performance. It was also soothing noises, fluttering lights, the illusion of tactile sensations, and fun.  That formula has caught on. For Daniel Canogar and Mika Rottenberg, it comes with obsessions, surveillance, and danger. With Jennifer Steinkamp and Pipilotti Rist, the Flying Spaghetti Monster took over Chelsea, and with luck more modest and edgy performances are waiting to take it back.

That formula has caught on. For Daniel Canogar and Mika Rottenberg, it comes with obsessions, surveillance, and danger. With Jennifer Steinkamp and Pipilotti Rist, the Flying Spaghetti Monster took over Chelsea, and with luck more modest and edgy performances are waiting to take it back.

Sound as performance

I too sat in white at the island chapel and, when the artist objected, stood. The light and sound of Blue Morph go on only when someone does, and the ghosts above the altar amount a projection through the woolen knit. Still other white fabric presences hang from the ceiling, like witnesses. I could quote you J. L. Austin on performatives, words like "I do" that look like statements but act like acts. Austin did not have much to say about art, but he has definite lessons for performance. With the Victoria Vesner directing, the line between interactive art, ritual, a certain shared silliness, and a summer weekend in a public park was getting less clear all the time.

Vesner names Blue Morph for a "nanophotonic" butterfly. The species, that is, gets its pigmentation not from chemistry but from diffraction, like most feathers—or, for that matter, a proper contributor to electronic arts. These days, big-ticket installations recycle everything from plastic cups and coffee machines to past lives. Show after routine show recycles formulas in painting and photography, to the point that one medium quotes another, even in sound art. Now the Harvestworks New York Electronic Arts Festival recycles reel-to-reel tape, museum wall labels, folk rock, and old film. The interest, though, lies less in strict recycling than in inexact translation—between performance, memory, images, and sound.

Speaking of recycling, Governors Island is a fine place to go green. One can take in the view, grab a bicycle, or climb over the outdoor sculpture, like this summer's display of Mark di Suvero. Buildings are run down, abandoned, or historic, but one rarely huddles inside to make out ambient sounds. One thinks, too, of electronics as rough and aggressive, beginning with feedback and tape loops. Yet the sounds here lean mostly to barking, growling, chimes, or just plain static. One weekend, punk bands threatened to drown out them all.

Water, water everywhere. Rainforest in Fort Jay recreates a work of David Tudor, who made his name in collaboration with John Cage by nurturing randomness and silence. John Driscoll, Phil Edelstein, and Matt Rogalsky respect his interactivity of spare parts and spare noises, both like friendly space aliens and now in iteration V. Waterwall, by John Morton and Jacqueline Shatz, lines another old passageway with water falling on colanders—like a domesticated version of the bells by Stephen Vitiello on the High Line. Louisa Armbrust's Blue Swimmers approach a two-dimensional bar code and then return to life up close in black and white, like something out of a forgotten Olympic archive. For a moment, they disturb the soothing ambience of the present.

For all that, these are translations. Back on land, LoVid and Douglas Repetto take their title from Joni Mitchell's The Circle Game. The seasons they go round and round, but their painted disks are not going up and down—or indeed much of anywhere. Brendan Fernandes reduces museum labels for African art to a kind of sans serif code, as presumably an assault on impersonality and appropriation. Alex Chechile's Data Decay lets an audiotape produce pulsating colored strips, like a biological specimen under the microscope. It may not be much but, hey, only inches on the reel to reel. The greenest and most challenging, though, has no sound at all apart from voice-over memories.

Lisa Kirk is a natural for the island, as Kirk's performance art has dismantled claims to both Lower East Side and Brooklyn real estate. Backyard Adversaries seems out of place in a festival of sound, but perhaps something was lost in translation. Children occupy an unnamed Hudson Valley retreat (and one heck of a backyard)—a commanding tree-lined lake, a stone house, and purple wildflowers as tall as they. Indoors they play with what look like oversized marbles and skin lotion, and outdoors they make unlikely guerrillas or terrorists, with silvery toy automatic weapons. "It just seemed strange to me," a boy remembers, and "it was kind of confusing." It sure was.

Streaming video

Daniel Canogar projects his obsessions onto others. The projections only start with light and color, but that is an impressive beginning. Canogar's LEDs criss-cross half the darkened gallery, most often as strips of light. A projector above the door turns them now and again into speckled bands, with bright colors that periodically leap out toward the viewer and onto the floor. Another projector lights up at random the silvery face of DVDs, tilted at various angles like the tiled electronic portraits by Daniel Rozin. Their reflections, in turn, tile the opposite wall with ghostly faces.

There is of course a precedent for projecting light from above across the room, in the movies. The ripples recall the cells of a film strip, only the tape itself is from a VHS. The second beam functions as an actual theater projector, only it projects onto the DVDs their own contents.  At least three generations of technology overlap in just two works. The Spanish artist must enjoy how VHS beat out Betamax and is already obsolete, while the Web threatens to make DVDs history. Given the streams of color, he must appreciate, too, that the latest advance is called streaming.

At least three generations of technology overlap in just two works. The Spanish artist must enjoy how VHS beat out Betamax and is already obsolete, while the Web threatens to make DVDs history. Given the streams of color, he must appreciate, too, that the latest advance is called streaming.

The lens behind one's back recalls yet another generation of technology as well—surveillance cameras in public places. Who are those slippery faces anyway? I guessed at first that they were gallery-goers, myself included. But no, the DVDs hold Hitchcock's 1953 Dial M for Murder. Appropriately enough, the plot involves blackmail and murder, and the main action takes place in a single room, mostly through dialogue and faces. Appropriately, too, the movie immediately preceded Rear Window, about a photographer as eye-witness, which feminism has taken as emblematic of the male gaze.

When it comes to media, Hitchcock himself was looking both backward and forward. He was adapting a stage play, and he seemed to accept criticism of the film as stage-bound. In the wonderful book-length interview with François Truffaut, he almost cuts off Truffaut when they come to it. "There isn't very much one can say about that one, is there?" Yet he was also experimenting with low-angle shots to project objects in depth. Film fashion has only just caught up.

Canogar is into 3D, too. The tilted reflections distort faces as in yet another virtuoso illusion, anamorphic projects. For that matter, I have no idea how the colors make it off the tape and onto the floor—or how they stick to the tape in the first place. I shall take the gallery's word for it that a single projector simultaneously colors all the tape while leaving the wall behind them blank, and another single projector supplies and confines all the faces. I kept looking for another source, to help explain Canogar's intricate narrative of murder, mystery, surveillance, and exhilaration, but no. He calls the show "Trace," and he has done a good job of hiding his traces.

When it comes to video, Mika Rottenberg brings all her obsessions, with a bit less of the mystery. Not that one can always follow the rapid cuts and changing camera angles, though the narratives do run chronologically—through lettuce and rubber harvesting and processing, intercut with an obscenely obese black woman in a cramped interior. But one has no trouble at all sensing the pounding, shredding, and dehumanization. And some of the ritual is haunting and strange, like the row of holes through which five Third World workers must thrust their arms for washing. In her last show, Rottenberg cleaned up her act to the point of a fashion shoot, but now she sticks to her obsessions with women, body image, and forced labor. Now if only those obsessions did not seem to make their victimization come at the hands of the artist or the women themselves.

Flying Spaghetti Monsters

Who knew that the Flying Spaghetti Monster was coming to Chelsea? Do not even count Arlene Shechet's curls of fired clay. They are not getting off their pedestals any time soon. Do not count Adam Fuss's black snakes on an empty bed or the snaky blackness of his photograms on newsprint. A bare mattress alone, in another silvery daguerreotype, is that much more weighty and yet evanescent—not to mention unburdened of associations with Mercury, Tiresias, the Caduceus, vaginas, Victorian childhoods, and the British variant on the game of Chutes and Ladders. Today's kids would much rather have video games, and both Jennifer Steinkamp and Pipilotti Rist oblige.

Pipilotti Rist always delights in promises of guilty pleasures, although more often sexual than dietary, with sins of temptation always lurking beneath the innocence. An odd little altar of apples and video by the gallery entrance surely alludes to both. So may the projection onto underwear "collected from the artist and her friends and family," destined to become a buyer's tackiest and costliest chandelier. In a larger work, Layers Mama Layers, fabric both creates and dissolves walls, and strands of light spin across them. Herds of sheep wander there, too, making this practically a balanced meal. They press closely, carrying one into a blissful landscape to the tune of The Internationale, and who knows who will become dinner?

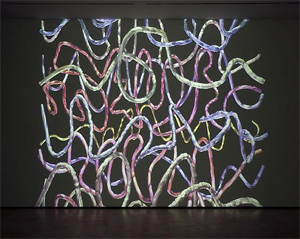

The strands take on a life of their own in Steinkamp's four projections. They, too, resemble snakes, especially when spots of light create bands of color. And their dense weave, too, evokes landscape, although not the grassy hills of Rist's native Switzerland. A fifth video in fact repeats Steinkamp's past motif—of autumn leaves and twisting branches. The fall season truly has begun. Most of all, though, they offer a new-media translation of Jackson Pollock, with their spontaneous weave, mural scale, and visual immersion.

Oh, yes, and spaghetti monsters. These artists aim large, but they are kids at heart. One set of strands descends, another twists, and the largest evolves even more mysteriously against its sweeping black background. The colors seem to respond to one another and to grow denser, but the space between them remains. They stick to a bright, familiar palette, again in deference to formalism. They depend, though, on fantasies of motion and flight. The wind-borne leaves make a video's asymmetry that much more obvious.

Rist is still over the top, although she has lost for now her daring when it comes to a woman's flesh and blood. Steinkamp is pretty much running in place after six years. Perhaps they are just holding onto a child's sense of wonder, a sense of beauty, and a sense of humor, and they do. Or perhaps they are caught in Chelsea's eagerness to entertain. I felt that in a low-tech disco floor by Zilvinas Kempinas, a Lithuanian artist. I definitely felt it with a French artist, Laurent Grasso.

Grasso could well have produced a Hollywood trailer, with a smart update of Alfred Hitchcock for digital production values. The camera moves at an improbable pace, penetrating further and further along a forest trail. Every few seconds a black swarm flies into the woods, and its sound comes out of half a dozen or so bulky old speakers. Grasso's nostalgia extends to two duller sculptures, allegedly devices for trapping dispersing sound, and to painting in oil that mimics tempera—like the predella panels at the base of an early fourteenth-century altarpiece. A man on horseback looks on as another geometrically studded orb hovers over a Tuscan landscape. An awful lot of artists in upscale galleries are looking at video with dreams and fears of flying.

The New York Electronic Arts Festival ran on Governors Island through September 25, 2011. Daniel Canogar ran at Bitforms through December 18, 2010, Mika Rottenberg at Mary Boone through December 18, Arlene Shechet at Jack Shainman through October 9, 2010, Adam Fuss at Cheim & Read through October 23, Pipilotti Rist at Luhring Augustine through October 23, Jennifer Steinkamp at Lehmann Maupin through October 23, Zilvinas Kempinas at Yvon Lambert through October 16, and Laurent Grasso at Sean Kelly through October 23.