A Wreck Grows in Brooklyn

John Haberin New York City

Jonathan Schipper and the Boiler

Lisa Kirk and Sarah Baley at the Navy Yard

Wrecks are coming to Brooklyn—but so is growth. Sometimes it seems that every installation has to show more and more muscle power. Cars are crashing and cruising everywhere. Now Jonathan Schipper watches entropy increase with a head-on collision. It marks his second work in a new gallery space from Williamsburg's oldest gallery.

In a recession, any new gallery is cause for celebration, right? Actually, no, but do make an exception this once for Brooklyn. The first week in March, Pierogi opened that second space, Boiler, for the display of large work. Will it last? One piece in the opening show is lucky to have lasted as long as it did. Even a block of ice now has a history.

Brooklyn had better beware of its melting. Before global warming raises sea levels on the East River waterfront, Lisa Kirk wants you to get a piece of the action. For a limited time only, her Lower East Side installation has moved to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which Sarah Baley takes as haunting ground for an evocative community. Will they start gentrification of those half-abandoned buildings and an old American Airlines fuselage? Shares in Kirk's housing have gone fast. Better act now.

At Kirk's ribbon-cutting in the Navy Yard, a crane stood desolate, and a huge ship docked off-shore. It might have parked there in World War II and never moved. In fact, people appeared on deck later that evening, and it had arrived the night before. We shared territory belonging to a fish importer, which had been fined, ominously, for too much shark. So which will do art in first, gentrification or trashy installations? Either way, drive carefully in Brooklyn.

Ninety-nine bottles of beer . . .

If there is any escape from another lap at Nascar, short of a pile-up, the video might have to run backward—or in slow motion. Jonathan Schipper manages both. In the Williamsburg gallery's large new Boiler annex, two cars go head to head, at an inexorable but imperceptible pace. Over the course of the exhibition, shared tracks bring them closer and closer together. After a week, the front ends showed some damage, and one windshield had cracked. Photographs of previous installations document more serious mauling.

The existence of photographs already says something: we have all been here before. The exhibition title, "Irreversibility," says otherwise. In its other work, Schipper plays more overtly on the arrow of time. A Corona bottle "thrown" across the room "smashes" against the wall. An inscrutable contraption then tries lamely to bring the pieces together.

Textbooks love to introduce the second law of thermodynamics with a coffee cup. Glass shatters, but the fragments never spontaneously reassemble. Anyone watching a film knows instantly whether it is running backward. (Helpfully, the gallery attendant has a clip on her laptop.) In fancier language, the entropy of a closed system tends to increase. Life or art requires energy from its surroundings, as in the appropriation of used cars.

Thanks to Thomas Pynchon, entropy became a metaphor for the postmodern narrative, without closure or symmetry. Its very subject ultimately vanishes into the stream of life. Too often, art's trashy installations between architecture and a wrecking ball twist Pynchon's fiction from subversion into dogma, without his comedy, ingenuity, or sense of history. They distrust high culture, but they accept cultural uniformity. Hit the road and grab a Corona. Try not to confront the actual gentrification of Chelsea or Williamsburg, where one can find a decent microbrew.

Schipper illustrates the narrative, but with a sense of humor about it. For starters, he only pretends to fling a beer against the wall. The same machinery that brings the glass shards together also carries them across the room in the first place. The cars self-destruct, but too slowly for visceral impact. He calls them The Slow Inevitable Death of American Muscle. Yet it takes muscle to press the cars so decisively together—and restraint to keep the damage under control.

In his heavy machinery and their elaborate timing, he has a kind of nostalgia for older narratives. In the opening show at Boiler, he contributed another tribute to Pynchon's uncanny pairing of paranoia and entropy, plotting and unraveling—a theme in art for Ed Atkins and his digital art as well. A sphere of small monitors spied on visitors, but spread their images in all directions. And it, too, looked quaint and clunky. As perhaps the greatest tribute to entropy, the beer machinery broke down before each of my visits, and I had to watch it on video. Each time, too, the attendant promised that it had been working only a few minutes earlier.

North by northwest

Of course, most artists barely get by, even in the best of times, and rising rents have claimed more victims than entropy, car wrecks, or falling sales. And the real growth has come at the high end more often than in Brooklyn. Deitch Projects, Nicole Klagsbrun, Taxter & Spengemann, and 303 have all expanded. The first extended its bloated empire to Long Island City—starting with Vanessa Beecroft's amalgam of sculpture, dance, hall of mirrors, buried civilization, and sheer pretension. Her dusty white female bodies on the floor evoke Pompeii, she swears, and not corpses left behind by the economy. The second adopted a temporary project space for Adam McEwen's allusions to heavy industry and missile manufacturing, the third leapt across town for a year to the lavish former studio of Frank Stella, and the last added a larger space only a block away.

One can see all this activity as a sign of hope—or sheer determination. It could also confirm the worst. As buyers retreat to safe choices, will only the big fish prosper? Must installations keep getting bigger and bigger to get attention? As the 2009 art fairs proved, a wider public for art is here to stay even with Bushwick Open Studios, and so is its taste for public spectacle. For all that, though, Pierogi is bucking the trend to complacency, even if I am not yet declaring victory.

One can see all this activity as a sign of hope—or sheer determination. It could also confirm the worst. As buyers retreat to safe choices, will only the big fish prosper? Must installations keep getting bigger and bigger to get attention? As the 2009 art fairs proved, a wider public for art is here to stay even with Bushwick Open Studios, and so is its taste for public spectacle. For all that, though, Pierogi is bucking the trend to complacency, even if I am not yet declaring victory.

Williamsburg galleries may have scattered to the winds, but the neighborhood pioneer is digging in. It is defying gentrification in another way, too, in a northwest industrial fringe past the Brooklyn Brewery. Even on the short walk there, with a school and tennis courts always in sight, I felt the fear of those same empty streets not so many years ago. The single room does not look larger than Pierogi's old winding space, except for its high ceiling. Now, though, big work can get in the door. It will just have to cope with the boiler.

That boiler, still attached to the front wall, gives the space its name. One walks around it from either side to enter, and it towers over everyone and everything within. Paradoxically, the 2.5-ton block of ice in its opening show could have calved from it. A dark sphere nearly my height and a good deal fatter could have fallen off. A painting of more circular bands could represent it. Each also recalls the spore-like shapes of Terry Winters—between formal structures and natural growth.

Actually, the arctic ice in its glass cube may have calved off a glacier. Flags flutter on high poles to either side, and screens at the base state wind conditions in two points of origin—one for the ice, the other for the work. Tavares Strachan first displayed it in his native Bahamas, and dry ice kept it intact on its way here, where rooftop solar panels power the cooling. It has lost only a few inches, while its sharp edges and transparency of ice have given way to something whiter and sleeker. (Just as in a home freezer, ice evaporates or, technically, sublimates, and I could not see a trace of water on the floor.) Pierogi hesitates to say when the show will end, but it promises to last the month before becoming bar supplies.

Strachan calls his installation The Distance Between What We Have and What We Want. Yoon Lee's painting, JFK, has a more overt futurism, but its sci-fi landscape, too, seems scraped together from the outer boroughs. From a distance, Schipper's sphere of flashing lights could mask a single human presence. Up close, the small monitors and cameras add up to 215 Points of View. Instead of the enclosed threat of surveillance, though, the gallery disperses a viewer's space, for now, into possibilities.

The gallery as gated community

For Lisa Kirk at her Lower East Side gallery, the challenge was, literally, to get in on the ground floor. Her Maison des Cartes (House of Cards) packs snugly into its tunnel-like space, where the work took ten days to assemble. A beach chair rests by its door, for what passes as leisure. From there, watch the abandoned tires on the roof, bend your head, and duck inside. A real-estate agent, available weekends or by appointment, will be happy to assist you.

The real-estate office has space out back, displacing the gallery owners. Clearly art and housing share the same bubble. You might sneak a peek at the manual that Kirk has prepared for her three-person staff, anticipating your every need—or, more likely, objection. It will teach you not to say much, but no matter. Grab a business card, look out for your wallet, and take a tour. On opening night, the diminutive but formidable head agent, Susan London, took charge, nonstop.

Kirk has constructed the monstrous shanty from found parts, including everything but playing cards. Rather, the title refers, among other things, to the unit's fifty-two shares. Former construction barriers form the living-room table. Orange plastic netting serves as a hammock—no, excuse me, bedroom furniture—able to accommodate a six-foot resident. And she has photographs to prove it. Besides, now that the Madison Square Tree Huts have come down, those displaced by Lower East Side art may not have many choices.

Eventually, shareholders will each carry away a fragment as a "unique artwork," assuming it and they survive that long. (Which piece? Co-op boards are facing more and more disputes these days.) First, though, the private residence has already migrated to the Brooklyn Navy Yard—a gated community, of course.

While the artist had planned to make the time share ready for occupancy after the show's closing, she landed a site in Brooklyn almost at the last minute. Bettina WitteVeen has since returned the Navy Yard briefly to life, but those going into real estate had better think quickly and be ready to deal with homelessness.

Kirk has a history of art about capitalism, seen as a system for branding is own decay as luxury goods. Only shareholders get a peek at an additional installation—below the floorboards but not, I hope, underwater. It recreates, she lets on, a combination terrorist cell and shop for "custom-made" perfume, previously at P.S. 1. There the elaborate messages swamped the work and something of her sense of humor. This time the work's bulk and conceptual layers could swamp almost anything, except its comic timing. She needed capitalism to catch up with her.

Blade runners

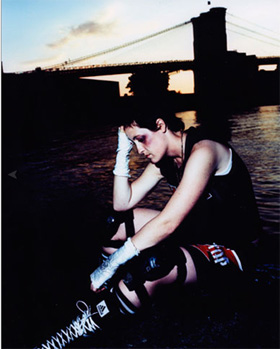

Sarah Baley's stylish photos of a seriously unstylish community have appeared in The New York Times Style magazine. And that raises more nasty questions, but stylish they are just the same. A young woman, head bowed, stands before the Brooklyn Bridge and a panorama of Lower Manhattan. Darkness drowns all of another woman but her face and the feathers around her neck. They share the vulnerability and glamour of the spotlight. They share, too, the warm red glow of the city at night.

Could those feathers belong to a live bird? Cindy Sherman might appreciate the echoes of Hitchcock in two blurred, wheeling swarms of them. Like a young couple clinging to each other for comfort, they punctuate the mostly color photographs with black and white. As with Cindy Sherman, too, the pageant has a running character hard not to mistake for the artist. She greets one by the door, in the same short blond hair and hunting cap as by the bridge, but clean, collected, and in a well-ordered interior. This, she seems to say, is the real me.

That frankness also serves as a warning. Before I go looking too hard for old stories, I should pay attention to a single new one. The same woman rests again against a night sky, but with a black eye and no one to explain it. Even the skyline forces one to fill in the blanks, in the present tense. Vans stop at a gas station and pack a parking lot. This is not On the Waterfront, but the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

It is also a community. Baley calls it "Bois." From the dark, treeless forests of Brooklyn, I want to pronounce it like the Bois de Boulogne. From the hints of the "Pictures" generation, I want to think of Yve-Alain Bois, the editor at October. A saner head, I bet, would pronounce it boys. This community goes for the hydrogenous look.

Like the waterfront, it also lives on the edge. Catherine Opie would understand its codes. The heroine wears nothing like a shirt or bra beneath her Rollerblades, hunting cap, and flak jacket. She has little though, of Opie's deadpan defiance. That couple clings beneath the scrawled word Peace, as if afraid to believe it. The blader has a black eye.

Can a community like this last? Does it even exist, outside the photographer's imagination? It makes a good antidote to the trust in youth of "The Generational," at the New Museum. Still, like New York, it has all the advantages of a young imagination. Churn out portraits of a neighborhood, and no one might recognize them. Recycle images from the movies, and one may finally see Brooklyn.

Jonathan Schipper ran at Boiler@Pierogi through June 28, 2009, Lisa Kirk at Invisible-Exports through March 29, and Sarah Baley at Collette Blanchard through June 17. Pierogi opened its Boiler space on March 4, with the three-person show of Schipper, Yoon Lee, and Tavares Strachan that ran through the month. Kirk's "House of Cards" had its ribbon cutting at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on May 27, and Susan London was actually Elisa London, a talented performer. A related review picks up Lisa Kirk in 2013.