Ditties of No Tone

John Haberin New York City

Soundings: A Contemporary Score

The String and the Mirror and Sound Art

"Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter." John Keats did not know about sound art.

"Soundings: A Contemporary Score" does not have Keats in mind either. Its reference points are almost the antithesis of Romanticism, in avant-garde classical music, science and technology, a subway station, and MoMA's permanent collection. Not a Grecian urn in sight. Where Keats all but stands for the western canon, it has a determinedly global cast. Even the two artists most familiar to New York galleries, Susan Philipsz and Luke Fowler, are Scottish. The handful of Americans have strikingly varied ancestries, with the last names to prove it.

Yet the Museum of Modern Art, like "The String and the Mirror" downtown, could well be quoting him. Did Keats intend irony, in praising unheard melodies in poetry, not long after "Ode to a Nightingale" at that? Or did he intend a new model for poetry, one that exists only on the page and in one's head? With a poet this dense, probably both at once. Regardless, "Soundings" is far more Romantic and nostalgic than it lets on. Often as not, its sound art pipes in ditties of no tone.

Composed by listening

"Soundings" starts so quietly that one could walk right past its first work. An ordinary bench from a subway station could easily belong to the museum's design collection or hallway fixtures, except that it badly needs a paint job. It is also the single work that one can touch. Sergei Tcherepnin has lined it with transducers, the same devices that convert sound into electrical impulses for a microphone. Here, though, they deliver not only near-silent audio transmission, a more than half-hour composition that elaborates on its environment, but an unnerving jolt to anyone looking for a seat. In Keats's terms, they play on, not to the sensual ear, but to the buttocks.

Motor-Matter Bench sets the tone for "Soundings," right down to its blocky wood surface—which could stand equally for that challenging response to the listener and for the show's limits despite so much art like this worth remembering. Too often, for all the artists' care, MoMA's idea of sound art skimps on more than sound. It is also way too short on subtlety, history, and brains. Anyone expecting a survey of sound art will wonder at how much is missing. At its best, though, it listens to a wider sonic spectrum and, like Tcherepnin, gives a serious jolt to ambient music. It also brings an unfamiliar sound to some familiar shapes.

In real life, not all of sound is audible, and not everyone can hear. Other artists convert the sounds of the museum and its visitors into water waves, the breeze from a fan into the motion of piano strings, and inaudible frequencies into something like nature's own music. Christine Sun Kim, who was born deaf, draws on musical notation and American Sign Language to riff on "thirty-two years of silence." As Tcherepnin says about himself, these artists are concerned for the "materiality and variation of sound." They are out for something visceral. As Carsten Nicolai says about the waves in his glorified fish tank, "our body is sound"—and if there were ever an "absolute silence" of empty spaces, "our human presences negate it."

As Nicolai suggests, unseen presences are not all that distinct from absences, much as for any sound recording. A spoken voice, which Jacob Kirkegaard has rerecorded to the point that it becomes unintelligible, repeats a single message alongside images of a devastated Chernobyl: "I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now." Absence itself becomes visceral for Susan Philipsz, with a wall of eight speakers in an otherwise empty room—each with a black circle beneath crossed by the speaker's shadow. Philipsz, who before has given her delicate soprano to the haunted in the Benjamin Britten opera The Turn of the Screw, here plays an orchestral work first staged by the doomed in a concentration camp. She also omits two of its voices.

The hauntings extend to another running theme, the uncertain place between humanity and nature. That fan touches a billowing fabric screen, which in turn sets off the nearly inaudible drone of piano strings. On one side, Luke Fowler and Toshiya Tsunoda project human settings that reach for the outside world, like a patio or a studio. On the other, slides convey blown leaves, as if the wind had entered the museum. As for nature's music, Jana Winderen captures ultrasound from fish and bats. Their dull roar in a dark gray room could stand for disturbance, their steady chirps for peace, or (depending on one's fears of zombies and bats) vice versa.

Hong-Kai Wang aims for an explicit sociology of sound. Her two-channel video travels from fields of sugarcane to the interior of a refinery. It also unites its own making with that of the agricultural product. Retired workers and their spouses wander about with a hand-held microphone, recording the slow action. Wang hopes "to paint a world composed by listening." The whole exhibition turns on whether these artists can.

Unheard melodies

The silences of "Soundings" extend to much of sound art (although a film series fills some gaps). The curator, MMA's Barbara London, does not intend a survey, and her "contemporary score" includes less than a score. She sticks to sixteen artists, all but one with a single installation. No one is over fifty, so this is not about the past, and no one is under thirty, so it is also not exactly the future. Almost all the work is from the last two or three years, so firmly in the present. For all its global reach and its insistent art, that leaves more than its share of unheard melodies.

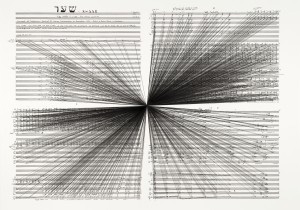

The catalog cites a broad cultural and artistic history. It notes the origins of sound art in crossovers between classical music and performance art, with Iannis Xenakis and John Cage, and between new media and performance, in the collaborations of Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman. It mentions computer music, rock, and punk. And yet none of that appears, beyond perhaps Music for Airports, although Marco Fusinato connects the dots in a score by Xenakis as his Mass Black Implosion. The oldest work, from 2006, pays tribute to Alvin Lucier, who used rerecordings as far back as 1969. Kirkegaard calls it AION (after Lucier), or infinity, as if the present moment has always existed and will never end.

New York has had more than enough other models of sound art. A retrospective of Christian Marclay provided quite a few all by itself, in the space between the visual arts and music (and my reviews of him run through many others as well). "Blue Smoke" at the Whitney looked for common ground in free jazz and Afrofuturism. Perhaps jazz for Herman Leonard, the found harmonies of Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, the "gamelatron" of Aaron Taylor Kuffner, or the surround sound of Janet Cardiff would here have sounded too musical. Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet, after Thomas Tallis, in fact returns to the Cloisters in September—soon after Philipsz brings "Taps" to an old fortification, with a permanent installation on Governors Island. "Soundings" may lean toward no tone, but it is also not terribly atonal.

New York has had more than enough other models of sound art. A retrospective of Christian Marclay provided quite a few all by itself, in the space between the visual arts and music (and my reviews of him run through many others as well). "Blue Smoke" at the Whitney looked for common ground in free jazz and Afrofuturism. Perhaps jazz for Herman Leonard, the found harmonies of Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, the "gamelatron" of Aaron Taylor Kuffner, or the surround sound of Janet Cardiff would here have sounded too musical. Cardiff's Forty-Part Motet, after Thomas Tallis, in fact returns to the Cloisters in September—soon after Philipsz brings "Taps" to an old fortification, with a permanent installation on Governors Island. "Soundings" may lean toward no tone, but it is also not terribly atonal.

For all the absence of the past, though, the exhibition shares a weakness of much sound art, its nostalgia for what it cannot hear. It leans to dated technology akin to that in photographs by Everett Kane, like the film and slide projector for Fowler and Tsunoda, and past art, like an installation by Haroon Mirza of a pulsing bicycle lamp, a classy Danish side table, and a composition by Piet Mondrian. Richard Garet stacks old speakers, an amp, and a turntable, whose upside-down platter fails to carry forward a marble. (He thinks of its futility as the myth of Sisyphus.) For Camille Norment, light through an old microphone casts flickering shadows, like a mask or a cage. Billie Holiday's generation would have used a mike and stand like this one, but they are long gone.

Even Kirkegaard's water tank bisected by a diagonal mirror looks to the past, in Minimalism, if a rather fussy one. So does a dense grid on the way in, by Tristan Perich. The fifteen hundred speakers in Microtonal Wall add up to a blur, but up close, and I mean close, each emits a single frequency. Out in the garden, Stephen Vitiello could make one nostalgic for all of New York. As on the High Line in 2011, each minute chimes with the bells of a site in Manhattan, and all play together on the hour. I caught a childhood favorite, the Delacorte clock at the Central Park zoo.

Like Vitiello, much here takes seeking out. It takes some hunting to find the "Bauhaus stairs" off the photography galleries, with three speakers and three pixilated color photos from Florian Hecker, one on each level. He means to create a dislocation, in contrast to the spatial illusion of twin stereo speakers, although I heard much the same bouncy beat in three clear and distinct locations, like a cross between white noise and the Strokes. The hunt extends to meaning, too, since most of the work very much needs its wall text. And, taken on its own terms, almost all of it works. For now, rather than sounding the depths of sound art, one will just have to settle for ye soft pipes of noise.

Sound awake

Is "Soundings" too close to easy listening? Does its white noise remind you of what you use to fall sound asleep? Maybe so, but you had better be awake and alert for "The String and the Mirror." This sound art is almost devoid of sound, not to mention established artists. It does not, however, lack for ideas. As curators, Lawrence Kumpf and Justin Luke see art as directions, not so much for performance as for making and remaking thought.

If that sounds less than intelligible, start with some simpler words. Now, words can easily spill into song, as for Anri Sala, but C. Spencer Yeh sticks strictly to vinyl lettering, more or less at eye level throughout the gallery. By their placement alone, the four texts leak into adjacent work. Their Bad Ideas for a Sound Mind also sound like performances you will be reluctant to carry out. One encourages you to hunt for money buried under a ceramic tile floor, but with dentist drills amplified through headphones. Another lets you off easy, to create a time capsule of yourself screaming, assuming you may wish to be remembered that way in one hundred years.

Another pretty much rejects the idea of sound as sense, with speakers mouthing "marble mouth" with a mouth of marbles. But then the whole late late summer group show sees sound as a kind of silent comedy. It permeates the gallery, like Stefan Tcherepnin's Concrete Mandalas of hard and soft materials that responds to vibrations, including curtains and beer, in tribute to The Tonic, the nightclub that was the site's former tenant. (I presume that he is the older brother of Sergei at the Modern, and both have left their own past compositions behind.) It might register on Alan Licht's decibel meters—or not, like Rolf Julius's Two Stones Singing or Marina Rosenfeld's "sublimated" music in 3D prints herself performing. Like Akio Suzuki's Bamboo Harp of only bamboo, it might have suffered from human intervention or badly need more.

Like much sound art, the show lingers over obsolete media, but without the reverence. James Hoff writes Hey Hey in cursive, with audio cable—as a plea for attention, rhythm and blues, or just plain derision. Christof Migone all but shouts "Back to vinyl," but as circles of opaque dust on the floor. Seth Bluett slices cassette tape into worm-like strips, with their outlines in charcoal as 100 Circles for the Mind. The only whirr comes from Matthieu Saladin's spinning Euro coin, at the end of a table that seems to have run out of the wherewithal to make music or political economy. And the sole audio is ultrasound, from Dave Dyment's pest-control devices, as if sound art had emptied the gallery of life.

This can get as knotty as it sounds. Like Mattin's Negative Press Release or Ultra-red's School of Echoes, it can involve opaque texts on the point of becoming sound—or words left over when the sound has died away. Essex Olivares (really Eve Essex and Juan Antonio Olivares) convert the back room into a semi-private office, with a corporate system for you to create sound in a conference that may never end. Melissa Dubbin and Aaron S. Davidson make jewelry out of the materials used in recording. Lawrence Abu Hamdan's "voice maps" look like colorful circuit boards, but apply existing algorithms to pleas for asylum. In each case, a political context inters sound as image. Whether convention shapes the very nature of sound is harder to say.

Can conceptual art become material? Could it even be audible? Like "Soundings," this show explores the "physicality and materiality of the aural." Sound can be disorienting, it insists, but not just to the human body. Rather, sound and ideas alike have a way of penetrating their surroundings, and that makes them difficult to contain. Before you know it, you and they together will have slipped away.

"Soundings: A Contemporary Score" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through November 3, 2013, Janet Cardiff's "Forty-Part Motet" at the Cloisters through December 8, and "The String and the Mirror" at Lisa Cooley through August 28.