Postwar Art in Ruins

John Haberin New York City

Sigmar Polke and Heidi Bucher

For nearly fifty years, Sigmar Polke painted a Europe in ruins, but the ruins of what? He himself seemed never to know for sure. His art shifts from medium to medium and allusion to allusion, often as not within a single painting or a single image. For Polke, it all blends together, as one tawdry spectacle that passes for history.

Seeing his MoMA retrospective is watching him throw one thing after another at the wall to see what would stick—and then delight all the more as each one comes crashing to the floor. All one can say for certain is that the ruins involve Germany, a Germany contaminated by both east and west—and a source of contamination from within. His work never coheres and hardly develops, right down to his death in 2010. At its best, though, it speaks to the creativity, incoherence, politics, and history in the art around him, as Modernism gave way to Postmodernism and the present. Its studious turn from Neo-Expressionism to irony also makes an illuminating contrast with Heidi Bucher in Switzerland. She felt European culture as a deeply personal experience, right down to her skin.

The living stink

When it came to ruins, Polke had ample choices. Would it be the ruins of German cities after Allied bombing or the ruins of Eastern Europe at the hands of Germany—of Eastern European art in the Cold War? Would it be the ruins of a nightmarish plan for the whole of Europe under the Nazis or the ruins of an older and wiser European culture with Germany at its center? Would it be a Germany divided by the Cold War or by the cultural turmoil of the 1960s? He had good reason to think of them all. In a retrospective called "Alibis," he can take them all as his life story, but he may still have trouble assigning or assuming responsibility.

Polke could be summing up that story with a 1983 painting, The Living Stink and the Dead Are Not Present. The acrylic on floral fabric centers on stacked rectangles, like the archived volumes in Goethe's Works from 1963. It has the decorative patterns of anything from folk art to flower children, much as a short film from around the same time spins off from a government-sponsored horticulture show. It has inscrutable hieroglyphics and maybe even an elephant or two. The dead may not be present, but they still outnumber the living. As for the stink, the flowers may be covering it or supplying it.

And the stink starts early, in a career that surely sets a record for swastikas in contemporary art. Early paintings and prints take up the artifacts of wartime rationing in soap, chocolate, a blanket, and cream-filled biscuits. Potatoes mark the nodes of a wooden hut, and "Mother," a watercolor helpfully explains, "is cooking socks." Barely decipherable bathers look more like a UFO sighting than a weekend at the beach, while a supposed UFO looks more like floating refugees out of Marc Chagall. Other paintings present a perpetual carnival of exotic dancers, from Japan in 1966 to New Guinea in 1980. Past or present, Polke's world is amusing itself to death—whether First World, Second, or Third.

Not that Polke exactly sympathizes with the carnival or the displaced. A hare out of Albrecht Dürer, stripped of all but its outlines in sausage links, reduces art and observation to the coarse appetites of a common culture. A blond tennis player and a family with children in lederhosen depict Germany's "master race" as vacuous and insipid. It just had the terrible misfortune of leaving its mark everywhere. In Polke's Europe, the potato house fits right in—except for one thing: he set to work in the 1960s, and he was only an infant at the end of the war.

Not that he is in denial of his adult years. He shows both the Soviet-style housing of Eastern Europe and a luxuriant weekend home, as a Graphic of Capitalist Realism. His frequent stippling derives from the screen prints of Andy Warhol, as does the vision of death in a portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald, and from the Ben-Day dots of Roy Lichtenstein, as does the crude rendering of a bathroom. He merely amplifies the cruelty, by forcing pigment through a metal grating of his own devising. He adapts happily enough, too, to the psychedelic era, with Chairman Mao and giant mushrooms in ghostly negative. Once again, though, he takes his time to confront what he has seen, this time until 1972.

He may not, in fact, believe in change. World War II lingers in a military chart, and it does not look all that different from a sky chart hanging nearby. Police kneeling behind a pig could belong to any number of crackdowns or totalitarian states. It took until the 1960s for the police to be "pigs," but then Europe needed pigs to root up all those potatoes before. Who is to say, too, whether Polke is complaining? He called abstractions from the early 1980s Disasters and Other Sheer Miracles, and for him the one true miracle is the spectacle.

All along the watchtower

Polke lays down a challenge to forget the disasters or the miracles, but also a challenge to remember. He belongs to a brief wartime generation unable fully to do either. Born in 1941 (the same year as Markus Lüpertz), he could neither have experienced Nazi rallies nor know them only as the past. Georg Baselitz and A. R. Penck, just a few years older, each developed a symbolic language for suffering—while Jörg Immendorff and Anselm Kiefer, just a few years younger, picture German culture as a total work of art without a final curtain. Gerhard Richter, born in 1932, and Isa Genzken, born in 1948, found their artistic and political traumas in the present, seen as an age of terrorism and illusion. Polke needed far more time to catch up.

His family escaped present-day Poland, first to East Germany and then to West Germany in 1953. He studied in Dusseldorf, when the Cold War raged in art as well as life. If early Modern movements, like the Bauhaus and Futurism, aimed to remake life, postwar art had to settle for making myths. Abstraction declared a new internationalism, one able to accommodate European refugees like Hans Hofmann.  So in its own way did Pop Art, and America had a head start on both. In Germany, Joseph Beuys, who volunteered for the Luftwaffe, was old enough to convert his personal history into its own myth. Other than some new painterly media, such as resins, nothing much changes from the moment he discovers them all.

So in its own way did Pop Art, and America had a head start on both. In Germany, Joseph Beuys, who volunteered for the Luftwaffe, was old enough to convert his personal history into its own myth. Other than some new painterly media, such as resins, nothing much changes from the moment he discovers them all.

Polke starts making fun of Abstract Expressionism in scrawling insults on canvas that influenced Albert Oehlen, the movement's agonies translated into text. He is still acting out his ambivalence in Color Experiments years later. He also had his Rorschach paintings, much like Warhol, not to mention those screen prints and stipples. Again, though, his ambivalence extends just as much to slick surfaces and commercial culture as to fine art. When he places multiple copies of Superman in the supermarket, neither, he makes clear, is all that super. He finally reaches America and the Bowery in person in the 1970s, when he lingers too long over the gutters and invites collaboration from Captain Beefheart, the blues musician with the Magic Band.

He differs from his influences in slipping casually from subject to subject and method to method. The retrospective runs more or less chronologically, after a kind of greatest hits in the atrium. And then things seem to die almost as soon as they begin. The curators, Kathy Halbreich with Lanka Tattersall and the Tate Modern's Mark Godfrey, omit wall labels in favor of tedious gallery maps as handouts. Even if one can match the dates and titles to the works, which is unlikely, one will still be scratching one's head. Who can say what to make of half the images, from herons to nineteenth-century illusionists, other than Polke's abundant ego?

Yet he differs, too, in his dislike of myths, even his own. Where another artist would represent the space age or drug culture, he has Polke as Astronaut and Polke as Drug, irony definitely intended. If he came late to abstraction's or Pop Art's party, he also came early to their revival. From his text insults before Christopher Wool and Richard Prince to irony as an end in itself, he anticipated much of painting today. He called another painting Seeing Things as They Are, with those words painted in German on the reverse. More like the "Pictures generation" than Pop Art, he was out to see through things while reading them backward.

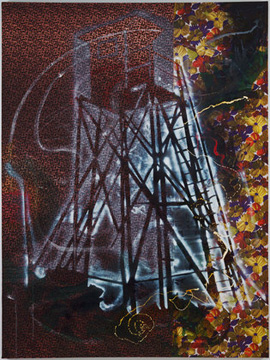

Polke comes off best when no single disaster has the final world. In painting on fabric from the 1980s, looming watchtowers could belong to concentration camps or the Berlin Wall. Their towering skeletons even recall Monument to the Third International, when Russian revolutionary art still seemed a miracle. The look of raw film footage belongs to Postmodernism, and then to its right one hundred flowers bloom. One could dismiss the whole show as scattershot self-indulgence, and mostly I do, but one could say the same about art after him. Yet he left behind a living history.

Skin in the game

Talk about having skin in the game. Heidi Bucher's late paintings have the look of animal hides or of soiled and stained human flesh, and she called them Skinnings. Think back to Jackson Pollock, with every drip the expression of thought, vision, and physical sensation in action. One can see that expression as liberating or painful, especially in the spare black contours of his last years. One can see him as putting his body on the line, in his work as in life—and ultimately losing it. For Bucher, too, art is a real and present danger, but she also locates its origins in European history.

A formalist might prefer to think of Pollock's work as the expression of its materials and the room, and Bucher's brown surfaces carry the scars of architecture as well. The Swiss artist laid fabric or rubber against doors, walls, and floors. Then she layered them with latex and, at times, mother-of-pearl before peeling them away. Villa Bleuler from 1991 preserves the tiling of a nineteenth-century estate, a fine mosaic in which the circles themselves spiral outward and peel away. Others from 1980 until her death in 1993 have the outlines of brickwork or the broad wood frames of old windows. By far the largest lies flat on a low pedestal, its edges curling only slightly further off the floor.

The palpable damage is clear, from arbitrary cuts into the rectangle to a mark close to a branding, and Bucher takes things personally. Fabric can evoke worn clothing and the mother-of-pearl nail polish. Yet she takes little pride in textiles as the materials of craft or outsider art. She also takes things artistically, from the patterns to the broad frames, marking paintings as both abstract and a window onto a world. Peelings from the floor hang on the wall, upending their origins. Paintings linger over the edges of the grid, much as for Jasper Johns in encaustic, and they look even thicker than they are.

Jason Clay Lewis would love you to look out for your flesh. He calls his show "Imminent Danger," and he wants you to feel every brushstroke as a cut. He speaks of hanging knives from the ceiling, although I did not see them. He speaks, too, of producing each painting with a knife blade. He could well have painted over a white ground, then incised into the black to reveal the radiating lines and the danger. The gallery swears that he actually painted in white on black, based on experiments with a knife, and I am glad I was not the subject of the experiments.

In effect, he sketches with a knife and paints to make the sensation last. And the sensation is less of a threat than of sheer welcoming energy, in radiating patterns like magnetic fields. The black can seem to pool itself near a painting's center, while the white cuts away irregularly with a momentum of its own. They might have taken shape all at once the moment before. Where Bucher starts with architecture in order to produce the skin of a painting, Lewis starts with a knife in order to produce the dynamism of abstraction. His could be the present moment to her deep past.

Bucher remembers, because she lived through too much to forget. Her work is a kind of urban archaeology, matching the practice of historians who press paper to carvings to record them for posterity. The process also insists on its deliberation. The raised floor piece has the scale and luxury of a Persian carpet. Unlike Pollock, Bucher made it well into her sixties. Viewers, too, will take their time.

Sigmar Polke ran at The Museum of Modern Art through August 3, 2014, Heidi Bucher at Alexander Gray through May 18, and Jason Clay Lewis at R. Jampol Project(s) through May 11.