Bringing Older Art to Light

John Haberin New York City

John Opper and Raymond Hendler

Claire Falkenstein and Milton Resnick

Just how good are they? With so many claims for major rediscoveries, some quite valid, it may seem defensive to wonder. Still, the question keeps nagging at me every time I delight in a discovery myself.

Galleries are discovering older as well as emerging artists, while museums are discovering women and the world. And while the textbooks may not be changing, some hope to rewrite a story central to Modernism—art after World War II in America. Two examples, John Opper and Raymond Hendler, point to the dynamics of recovery and the difficulty of judging. So does Claire Falkenstein, who sat out critical years in Europe. Meanwhile an artist who never altogether disappeared, Milton Resnick, is gaining attention nonetheless, but not just for what one might expect. Galleries are taking up his dark abstractions, but also his late turn to figurative painting and the light.

How good are they?

I hate to ask how good they are for another reason as well: I favor criticism that illuminates rather than judges. I want to give others the grounds to decide for themselves. I have to admit, though, that I am as subject to the excitement of discovery as anyone else—and as subject to doubts. At least two shows have had my moods swinging wildly. Maybe that is because they concern a favorite subject of mine, postwar abstraction.

While artists hoping for success fear a bias toward the tried and true, they live in a time of upheaval. Museums are looking beyond white male Americans, while galleries are rediscovering older artists, even as they tout the new. Often as not, too, these trends come together. They do with renewed attention to South American women in the twentieth century, from Tarsila do Amaral to Lygia Pape. At least one Chelsea gallery, though, prefers New York's hidden history. Take its last two shows, John Opper and Raymond Hendler.

Both started early, just past the peak of Abstract Expressionism, and both took time to settle down. Opper seemed at last to have absorbed his friends and influences, and his show covered just a few years around 1970. He began to distill his gestures down to strong verticals. Oil soaks into the canvas and depends on that for its sense of stasis. The lozenges play the role of rectangles for Mark Rothko and share his early yellows and reds, before Rothko's turn almost to black. As the edges soften, the shapes swell outward and become more luminous.

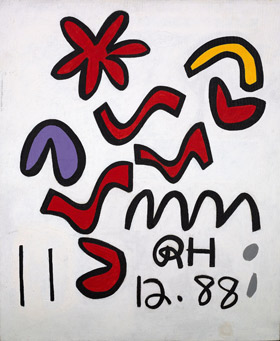

Where Opper was settling down, Hendler was shaking things up. His show covers fifty years, up to his death in 1998. The early painting, though, comes almost as an afterthought, with good reason. A few small works in the back room look dark and clotted. He actually grew more gestural in the 1970s, like Stanley Boxer with his ribbon paintings, just when art was moving the other way thanks to Minimalism. Yet Hendler, too, was boiling his gestures down—only to thick black squiggles and a few blasts of cartoon color against mostly white. Where Opper moved toward color-field painting, he skipped right past it on the way to finding his signature.

He did so literally at that. He signed and dated his paintings as an equal part of the work. The month and year look as bold as the more abstract squiggles. Where Philip Guston abandoned Abstract Expressionism for a comic-strip flair akin to Pop Art, Hendler found a way to merge the two. If Opper had me both loving and hating that I had seen what he did before, Hendler has me smiling at something long overdue. It also connects him to more contemporary work, from text art and dated panels to graffiti.

And then the doubts keep creeping back. Neither artist gets over the arbitrary placement of gesture and color, and no one can be the next Rothko or Guston. Maybe the first trend, toward gender and multiculturalism, stems from politics and the second, for older artists, from markets looking for something big. And we know how crass markets are—and how easily manipulated. Is that altogether bad, despite postmodern critiques of cultural dominance? Maybe it is a good thing that I am having trouble judging.

A Tangled Web

Claire Falkenstein all but went out of her way to avoid fame and fortune. She studied and taught in the Bay Area, like Clyfford Still, but before the West Coast art of Deborah Remington, Jay DeFeo, Bruce Conner, and Mary Corse. She left for Paris in 1950, just as the scene was shifting to New York. Even there, she moved among such Californians as Sam Francis and Mark Tobey as often as Alberto Giacometti and Jean Arp.  She incorporated colored glass into her wrought copper and steel, when critics might have written it off as feminine or craft. Even now, one cannot say for sure whether she was ahead of her time or clinging to the past.

She incorporated colored glass into her wrought copper and steel, when critics might have written it off as feminine or craft. Even now, one cannot say for sure whether she was ahead of her time or clinging to the past.

Why not both? They add up to a singularly informed Modernism, in a gallery retrospective. At its very start, a bulging pillar of wire from 1963 recalls a younger San Franciscan, Ruth Asawa, but without Minimalism's self-control. And the tangled web she weaves extends from her sculpture to her history. Born in 1908, Falkenstein learned from László Moholy-Nagy, who knew at first hand both the Bauhaus and Dada, and she took that confluence of geometry and rebellion to heart. She learned, too, from Alexander Archipenko in her merger of Cubism and abstract art.

Sculpture in wood from 1942 closely resembles Archipenko's twisted bodies, but confined to the plane. Even earlier, her paintings bring Cubism to America. One looks much like a figure from Pablo Picasso set in a remote but spacious interior. And then her ceramics from 1939 and 1940 might have stepped right out of the picture. Their colored glaze also anticipates her later materials. Come to think of it, one work in wood incorporates shells, just as paintings from 1948 reside on cut and incised aluminum. Glass shards are not so very far away.

A denser tangle enters as well. It also draws her ever closer to Surrealism. Its fears appear in titles from 1947, The Plunge Overboard. She may have felt at sea after the horrors of war or on the cusp of Abstract Expressionism. Still, an early metal sculpture would like right at home with David Smith. Her later hanging wire drifts with air currents much like a Calder mobile. The gallery indeed titles the show "Matter in Motion."

Like Calder, Falkenstein never does put early Modernism behind her. Metal scraps from 1958 have a parallel in John Chamberlain, but without a hint of crushed autos and popular culture. Still, she is starting to run wild, with her signature wire over an armature of twisted metal cords. Paintings overlay tear-shaped white on fields of color, in squares or diamonds four feet to an edge. Throw in the deliberate sensuality and eyesore of broken glass, from around 1970, and she has found her art.

By then, she had returned to the United States, settling in 1963 in Southern California, where she remained until her death in 1997. She has the Long Beach Museum café named for her, but she had more acclaim than one might think all along, if mostly in Europe. Solo shows celebrated both sculpture and jewelry, and Peggy Guggenheim in Venice commissioned her largest work in metal and glass, The New Gates of Paradise. The reference to The Gates of Paradise, the bronze reliefs by Lorenzo Ghiberti, is typical of her attitude to the past, but then so is her refusal of Renaissance imagery. A painting from 1944 approaches Deux Enfants Menacés par un Rossignol (or "two children menaced by a nightingale"), by Max Ernst, in its collaged wood and disturbing perspective—and she never will free herself from old-world bad dreams. Yet its utility pole and the open road belong, for all her travels, firmly to America.

The not so great outdoors

Late in life, Milton Resnick could finally confront his demons. In 1986, nearing seventy, he began to work small while mixing his own paints—two solutions to an outsize need for control and a shortage of recognition and cash. It might have come as a disappointment or a relief, after so many big paintings as the scene of equally titanic struggles.  For nearly twenty years, they had approached monochrome or sheer black, but with thick brushwork that refuses any restriction to surfaces and uniformity. In a heated argument back in 1961, Ad Reinhardt had warned him against "work that's too available, too loose, too open, too poetic." Resnick might have been taking that advice to heart or arguing back.

For nearly twenty years, they had approached monochrome or sheer black, but with thick brushwork that refuses any restriction to surfaces and uniformity. In a heated argument back in 1961, Ad Reinhardt had warned him against "work that's too available, too loose, too open, too poetic." Resnick might have been taking that advice to heart or arguing back.

Besides working small, he was also indulging in color. Maybe color was at the heart of his work all along, even when it added up to mud. Now, though, he allowed different colors to appear side by side. They also opened the door to imagery. Work from the early nineties has bits of still life now and then, but mostly figures in a landscape. Whatever are they doing there?

A stickler for "pure painting" would have had to ask. So do over fifty works on paper, as "Apparitions, Reapparitions." Everything about them is as murky as Resnick's earlier impasto. The figures appear as sharp flesh tones and color against mostly green and an earthy red, but this is not the great outdoors. They may be male or female, resting or fighting, naked or clothed. By his death in 2004, he had added another motif, roughly an X, as if crossing them all out.

Resnick, the gallery notes, had his studio just across the street on the Lower East Side, and it is hard to keep his biography out of the picture. Born in 1917 in what was then, for a few more weeks, the Russian empire (but now Ukraine, where Lesia Khomenko in art assesses hopes for freeom), he escaped Bolshevism, anti-Semitism, and civil war with his family in 1922. He was at the core of Abstract Expressionist New York and exhibited with his older peers. I caught Resnick in 2001 at the gallery that also represented Lee Krasner—and he is still on the roster of a leading Chelsea gallery, with paintings from the early 1980s on board. Yet he had on again, off again solo shows and, like Sonia Gechtoff, had to live down the label "second-generation Abstract Expressionist." One can read entire books on the movement without catching his name.

He may have found in the 1970s a way to reconcile Minimalism and gesture. Yet he still came off as out of fashion or out of touch. He was plainly expressive, but as clotted as cream. Could the late work offer a fresh point of entry? It maintains his competing brushwork, but more clearly. It also adds, in the angels or demons, a metaphor for his difficulty.

The landscapes can be sunlit or fiery, if not exactly welcoming. Figures stick to the foreground, set horizontally, refusing a greater depth. In one, a naked man and woman stand off to the side, as if uncertain where to go. If this is Eden, they might be glad to leave it behind. The show has two earlier works, closer to the entrance. They look all the more ambitious once one knows that Resnick put them, too, behind him.

John Opper ran at Berry Campbell through March 10, 2018, Raymond Hendler through April 14. Claire Falkenstein ran at Michael Rosenfeld through July 20, Milton Resnick at Miguel Abreu through April 25 and at Cheim & Read through March 31. A related review sticks to the issues surrounding older artists and exclusions.