Painting Made Easy

John Haberin New York City

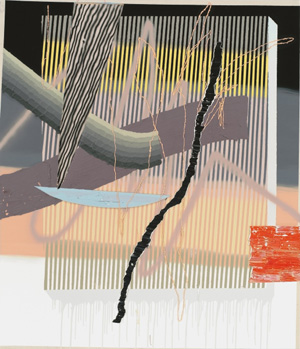

Post-Analog Painting and Clare Grill

Kes Zapkus and Iman Raad

Is painting getting easier? Maybe it is just spring, after a long and bitter winter, when people can hardly resist letting loose. Or maybe artists just cannot hold back any longer, after that still longer winter when painting was declared dead.

A spring gallery tour offers a good antidote to an awful winter, but mixed messages about painting. Several artists let loose without breaking a sweat, in a style one might call "business casual"—or what a gallery calls "Post-Analog Painting." They hint at a history of women in art.  Meanwhile Clare Grill and Kes Zapkus take sensation seriously, while Iman Raad refuses the still in still life. He treads lightly between Pattern and Decoration and war in the Middle East. Taken together, they suggest painting caught in both the risks and potential of its renewed success.

Meanwhile Clare Grill and Kes Zapkus take sensation seriously, while Iman Raad refuses the still in still life. He treads lightly between Pattern and Decoration and war in the Middle East. Taken together, they suggest painting caught in both the risks and potential of its renewed success.

Making a splash

A splash here, a spray of paint there, a squiggle or two on top—half a dozen shows could almost have come from a single artist. They value bright colors and open textures, for a glimpse of canvas or the sea, with sincerity or irony almost beside the point. It could, depending on one's mood, have one reveling in paint for its own sake or begging for more commitment and more paint. Just this past winter, many shows celebrated painting's potential, with such artists as Michael Goldberg. Could that celebration lead instead to slapdash solutions? I am not sure myself.

It is a fool's game to look for trends. The avant-garde is dead, and a sucker is born every minute, along with another fashion. In just the last few years, painting has kept returning to hybrids, between abstraction and representation, between analog and digital, or between media. It has had room for obsessing over geometry and gesture, expression and excess. It can get downright conceptual or, at the other extreme, derivative. In different ways, they all speak to a felt need to go over the top, not unlike market prices.

Could that same need have artists paring back? For Jack Davidson, a blot of color like toothpaste right out of the tube settles into craquelure with room to breathe. Lines for Tatiana Berg hint at faces, while the dabs of background color for Jason Stopa broaden into sky or sea, beneath marks like glints of light on a freshly cleaned window. For Shara Hughes, also an abstract painter, a studio interior facing an open window looks downright lush by comparison. Yet she, too, is becoming sparer, while moving her scenes outdoors. The four differ in overt subject matter, but not so obviously in their true subject.

Other painters were taking the easy way before them, to striking effect. Mary Heilmann still shows how to take the pattern out of "pattern and decoration." Jonathan Lasker recalls the dream of making paint look as good as it does fresh out of the tube. Nicole Eisenman allows her squiggles to cohere into schematic faces, much like Berg's. For the entirety of "The Forever Now," recently at MoMA, impulse aspires to a language of art. Trudy Benson riffs on that language as well as anyone. She sprays and brushes oil, enamel, and acrylic as if to exhaust the possibilities.

Lasker and Benson appear in "Post-Analog Painting," a near compendium of layered but open styles. Matthew Stone heads for Benson territory, with casual marks gathering in density while leaving plenty untouched. Mariah Dekkenga and Nathan Ritterpusch navigate between Paul Klee and spaghetti. If this seems a cartoon version of abstraction, sure enough Rachel Lord incorporates Angry Birds, while Josh Reames throws in a banana or two as well. Mark Flood tosses off a Jasper Johns flag as inkjet print, while Jeanette Hayes introduces Manga to Willem de Kooning. Never mind that Johns and de Kooning blew abstraction and pop culture out of the water long ago.

Is painting reclaiming ground late in the game, or is it losing ground to impulse and irony? Do artists have too much access to pop culture and art history alike, thanks to the Web? Does it matter that virtually none of "Post-Analog Painting" looks in the least digital, although Trudy Benson alludes to just that? One virtue of paintings like these is to keep arguments going. Besides, one can always lean back and enjoy it. Now if only it did not look so easy.

Beyond excess

Sometimes a lot of work leads to sensory overload. Op Art went for it, and so in a very different way did Pattern and Decoration. So, too, do some fine younger artists who keep one's eye moving across the surface, as with delightfully large and splashy paintings by C. Michael Norton on the Lower East Side.  They are not so much calling attention to themselves as keeping one off balance. Sometimes, though, a lot of work can calm things down. Take just two painters more than a generation apart, Clare Grill and Kes Zapkus.

They are not so much calling attention to themselves as keeping one off balance. Sometimes, though, a lot of work can calm things down. Take just two painters more than a generation apart, Clare Grill and Kes Zapkus.

Grill approaches monochrome, while Zapkus approaches a grid. Her surfaces, even at their brightest, come off as subdued. She might almost have rubbed them down until nothing remained but the weave of the canvas and their luster. His rely on short strokes and incomplete cells that function as gathering places for color. Splashes of paint never quite fill their cells but often exceed them. They allow one to appreciate the excess without taking leave of one's senses.

Both highlight what goes into their art's making or unmaking. They accept repetition, but also accident and self-effacement. They relate art to finding one's way in the world as well. Grill's compositions look like paving stones worn away by time. Zapkus finds inspiration in mappings and symbols, from Paris streets to sheet music. One diptych sets the standard projection of a world map against its abstract counterpart.

If one does not make the associations on one's own, fine, for he is also challenging the fixity of codes and the world. He has been at it a long time, too, starting with Soho gallery pioneers like Paula Cooper and John Weber in the 1970s. One can take him for granted or for business as usual, but he is still very much in business. Although he had a show of large paintings at O. K. Harris a few years back, one may also not appreciate just how much his incremental processes works on a large scale. One early work on paper presents a row of parallelograms, progressively leveling off as they march from left to right. Larger color fields help give shape and rhythm to new and larger paintings in much the same way.

Today's fondness for overload extends to well-meaning but outsize group shows, like "The Painter of Modern Life" and "Twenty by Sixteen," both in Chelsea. The latter refers to the uniform size of its paired canvases, but it could equally be called two by forty for the number of its artists. For all their solid choices, mostly abstract, they all but dare one to pause for long, to indulge in fresh discovery, or to remember half one's favorites. They rebel against those who mistake big money and big press for a new canon. Yet they also risk replicating the experience of the art fairs, and who am I to tell you where to begin? My job is to get you to look and to think—and so, I like to believe, is an artist's.

This is not about "slow art." Sure, one has to slow down now and then, but that tag can amount to a smug dismissal of art since Andy Warhol—or of simply whatever art one happens not to like. Pop Art, Minimalism, conceptual art, and Dada long before them all have their share of one-liners, but one-liners that come back to haunt one long after. The immediacy of a drip painting once felt like a betrayal, too, and even The Last Supper for Leonardo or Leonardo's Saint Jerome presents a moment in time as an explosion. No, this is about dealing with the quiet after the explosion is over and the moment has gone. And then one can honestly start looking and talking.

The still in still life

Most decent artists are in constant dialogue with their art. An exhibition of Iman Raad even has a message for him on the way in. The Hero stands more or less life size and more or less proud, a pennant raised above its bright orange face. It is a literal stick figure, in scrap wood with a makeshift easel for its chest and legs—and the easel bears a work in progress of its own. The portrait looks suspiciously like a stand-in for the artist, its studious face divided and overlaid with text: your body-of-work is a battleground.

The battle rages. Birds pack into and candles burn in paintings that refuse to accept the still in still life. Fruit spills out from white bowls painted with more fruit. The panels rest on patterned shelves, because color just cannot stop at their edges. Raad decorates the sticks of the stick figure as well, and the bright blue sticking up from either side of its comically round face reminds me of nothing so much as the pointy haired boss in Dilbert. The gallery's very office becomes a wall painting.

It also becomes the one obvious battleground. At its center, a grisly Middle Eastern face glares out from a warplane with buttocks for a cockpit and phalluses for jet engines. Fires with their own grim faces burn on all sides,  leaving figures of woe packed into the corners. Still, this is a Lower East Side gallery office, and Raad straddles East and West, with a hint that he has left the worst behind. He looks at once to Islamic art, Henri Matisse, and the modern still life—and no wonder. He is an Iranian and a graduate student in his late thirties at Yale.

leaving figures of woe packed into the corners. Still, this is a Lower East Side gallery office, and Raad straddles East and West, with a hint that he has left the worst behind. He looks at once to Islamic art, Henri Matisse, and the modern still life—and no wonder. He is an Iranian and a graduate student in his late thirties at Yale.

Plainly politics is on his mind, but he seems eager to leave that behind, too, for a more hopeful future. The likely self-portrait quotes Barbara Kruger both visually, with block text on black and white, and with its words. Yet it converts Kruger's alarming red bands into a more playful purple, and it lightens her feminist message: your body is a battleground. Notwithstanding the show's title, "Tongue Tied," sheer exuberance has the last word. The appropriation of the "Pictures generation" becomes one more excuse for excess.

He comes closer still to Pattern and Decoration. (He follows the most colorful show yet of Robert Kushner, with a similar emphasis on still life, scale, and overlays.) Raad approaches Rococo period rooms as well, such as Jean Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher at the Frick. Panels serve as paintings, furniture, and wallpaper. That points to his stylishness and ambition, but also lightness of tone. One need not take his battles too seriously.

Still, there are signs of melancholy, only starting with the portrait divided between black and white. The hero has a painful smile, candle flames reverberate in the fiery field of battle, and one candle lies broken in half while still aflame. A second and larger easel stands at the back of the gallery, as Unnameable, with the painting of a single flower. This time, though, the sticks flail out in every direction and threaten to bury the raw canvas. Raad still comes down on the side of pleasure, but he has received a warning. The decisive battle is yet to come.

Jack Davidson ran at Theodore:Art through April 9, 2015, Tatiana Berg at Thierry Goldberg through April 19, Jason Stopa at Hionas through April 25, Shara Hughes at American Contemporary through April 26, Trudy Benson at Lisa Cooley through May 3, "Post-Analog Painting" at The Hole through May 24, C. Michael Norton at Brian Morris through June 6, Clare Grill at Zieher Smith & Horton through April 25, Kes Zapkus at William Holman through May 22, "The Painter of Modern Life" at Anton Kern through April 11, and "Twenty by Sixteen" at Morgan Lehman through May 2. Iman Raad ran at Sargent's Daughters through April 23, 2017, Robert Kushner at D. C. Moore through March 11.