They Call It Motion Pictures

John Haberin New York City

William Klein and Ray Johnson

Muhammad Ali had not yet begun to fight. Getting set for the title match against Sonny Liston, he could barely restrain his anticipation, and he saw little need to try.

One can see it from his signature dance as he spars with the air. One can see it only moments before, still seated. He must have felt his heart beat as the trainers applied a stethoscope to clear him for combat, and they must have barely heard it above the noise of the crowd. Soon enough he is back on his feet and the scene shifts again to marchers for civil rights. Is it still the same movie? It is just one step in a world in motion, in photography and film by William Klein.

Start anywhere you like at the International Center of Photography, which devotes both floors on Essex Street to the exhibition, a first. How else could it keep up with Klein, who managed twenty-seven documentaries, three feature films, and TV commercials on top of his stills? It seems only fitting, though, to start at the top and work down against the tide, for an artist who always went his own way. That lands you in a makeshift theater, with no telling where a film begins or ends. It may come as a mere footnote to day jobs in fashion and celebrity photography, with street photography in abundance on the side. But Klein's photographs, too, are motion.

At his death in 1995, a suicide, Ray Johnson had dedicated himself to photography for just three years. It was enough to run through nearly two hundred disposable cameras. Did he see his work as disposable as well? The Morgan Library hopes to rescue him from the trash, as "Please Send to Real Life," composed of gifts from the artist's estate. He kept just a step away from fame, much like Klein, another hyperactive photographer of the very same age. Yet he had a far less certain idea of real life.

From photograms to photography

Art for William Klein began with motion, although he himself began as a painter, with a story that sounds deceptively familiar. Born in 1928, a white on the edge of Harlem, he moved with his wife to Paris, like Stuart Davis and others before him and for much the same reason—to be where the action is. Barely twenty, he worked with as modern an artist as Fernand Léger, but with an instinct for boldness, in thick crossings of black, white, and red. It caught the attention of an architect, who asked him to translate his design sense into something firmer still, panels for a home. But then his wife took them for a literal spin, and he knew that he needed to capture the changes. He made thousands of photograms in short order, by cutting circles and diamonds out of paper, moving them across photosensitive paper, and exposing them to the light.

Photograms most often mean placing a solid object on paper, as for May Ray. Yet here nothing is solid and everything is in motion. The image itself may pulse like an EEG or blossom outward like flowers. The panels alone look in motion at ICP, tilting into the space of the gallery. Before one writes off Modernism, though, as old school, Léger himself told Klein to give up painting for photography—just as he told Louise Bourgeois to give up painting for sculpture. Klein did not have much of a track record, but Alexander Liberman at Vogue spotted him as well land lured him back home to New York.

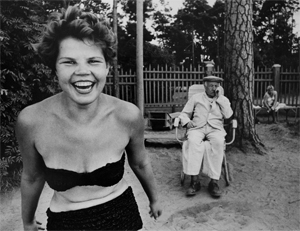

He still lived in Paris until his death, the very weekend that the show prepared to close, but the sophisticated European reclaimed his roots as a street smart New Yorker. His eye went everywhere, and what he saw was moving, too. Blacks dressed for the jazz age take their Moves and Pepsi. A man in the shadows of an elevated train steps toward the light. If Klein and his subjects share a Pop Art sensibility before its time, he also shoots a tabloid headline, Gun Gun Gun. Photography here emerges out of the barrel of a gun.

It had to, for his politics alone cannot leave him at rest in the present—or any one place in the world. He photographs black marchers for justice, a gay pride parade, a dance festival in Tokyo or Brazil, and a pan-African celebration of West African independence. Once in Algiers he met Eldridge Cleaver, the exiled "minister of information" for the Black Panthers and, in no time, immersed himself in Cleaver's life for three days and nights on his way to another movie. He had met Malcolm X as a seatmate on the plane, who took to him easily and introduced him to Ali, then Cassius Clay, for Cassius the Great. Another film became Mister Freedom, including a poignant shot of Mister Freedom dying. For Klein, freedom is always dying and coming again to life.

How does he deal with his day job? He takes his models with him to the streets. One juggles, creating broad traces of light right out of his photograms. Others pose outside a barbershop, as if mannequins for Gordon Parks had stepped out of a store window and into the light of day. Where other museums make the case for magazine photography and the "new woman," here genres themselves go out the window. Think of Lee Friedlander touring "America by Car" or Robert Frank and The Americans, but for mass transit and a multicultural America.

With motion comes multiples. Another film takes off from Klein's work in fashion, with the unlikely career of a fashionista played by one of his favorite models for Condé Nast, Dorothy McGowan. But then, as the film's title has it, Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? A dozen versions of her sit stand by side, while two dozen others sit on two-tiered shelves. When he shot Pelé, Pelé, Pelé, the three versions of a soccer star became at least seven actors—and, when Little Richard disappeared from the set of a movie about him, Klein simply put out an open call for look-alikes. Hey, I can almost hear him say, that is why they call it motion pictures.

Change as a state of mind

And yet not everything moves fast. Clay's supporters are everywhere, but off camera. The marchers hold their signs to the camera, which barely moves. (Orson Welles admired Klein's work, but not to emulate it.) The world is in motion, but only because lives are in motion, and one's story leads to the next. Cities, too, are in motion, but the real change comes within.

His breakthrough film, from 1958, dares comparison to Empire by Andy Warhol seven years later, with a single extended shot of New York. Yet Broadway by Night looks to Times Square, compressing its neon night into just over ten minutes, where Warhol took the Empire State Building as a model in real time because of its stasis. This could be the city that never sleeps, although its inhabitants may, since none is visible in the blackness. Instead, bright lights come in and out of view until black gives way to the blue of dawn. And then the camera closes in as if unable to let go of the dark. A changing city or a changing image is first and foremost a state of mind.

That sense of an inner life sets him apart from a younger denizen of Times Square, Diane Arbus. Klein is not a child of the 1960s, its disenchantments, and the creeps. Wherever he travels, he looks for hope. It can reduce the world to a perpetual dance party. Still, he sees in Rome a male world and its disenchantments, After the Parade. In Moscow, monuments and stolen moments alike labor under constraints. Then, too, a uniform vision is just another name for a style.

That style has its resonance for photography today. The focus on black America and the spirit of the streets appears, too, in Jamel Shabazz in the Bronx. If it is a trifle upbeat, it still began as a rebellion. Klein hated how photographers look at Paris and see only a "gray city"—"romantic, foggy, sentimental, and above all monoethnic." But then he never could accept Henri Cartier-Bresson and the "decisive moment." No one moment is decisive, before it moves on to the next.

ICP works hard to keep up. It has three hundred works, arranged roughly chronologically and in series, but it goes quickly, like the work. It has some of the original magazine covers and photo shoots that became books. Many more prints are larger now, in staggered arrangements like miniature cities on the walls. As curator, David Campany deserves credit, but many if not all the prints came this way from Klein's studio. As a foretaste, an early abstract print appears directly on the wall.

The show ends by circling back to the beginning, after the makeshift theater. Klein returns to photography and the streets of Brooklyn in 2013. He might never have left. He also takes up the brush again after all, in enamel, for his "painted contacts" in red, yellow, and blue. They recall the black borders of portraits by Richard Avedon, but they cannot stick to the borders or to black. They, too, are a state of mind.

Disposing of photography

Photos for Ray Johnson do seem disposable, like so many of his subjects and, ultimately, his life. He collaged movie stars, on cardboard roughly a meter high and on the smaller sheets he called his moticos, as motile and irregular as rubble. He photographed a manhole cover, tar oozing onto a parking lot, and a palm front left lifeless on sand—fragments of fragments, as fragments of an irregular vision. After his single-use cameras, he loved nothing more than a photo booth, the source of what most people throw immediately away, along with their memories of a shopping mall or Times Square. He burned every one of his abstract paintings from Black Mountain Collage, retaining nothing of his teacher but his advice. Josef Albers told students to destroy early work when they were ready to move on.

At his death at age sixty-seven, Johnson left behind more than five thousand color photographs, stashed in boxes with no obvious order or priorities—but then hoarders are always close to trash collectors. Still, he had an ambivalent relationship to art every step of the way. Black Mountain was always on cutting edge, and he knew it. He reconnected with a classmate, Suzi Gablick, now a critic deeply skeptical of Modernism, and he photographed the shadow of an Upper East Side dealer, Sandra Gering, on a Walker Evans photograph in 1992. She could only have been flattered. Yet he left for the suburbs in 1948 and never looked back.

At his death at age sixty-seven, Johnson left behind more than five thousand color photographs, stashed in boxes with no obvious order or priorities—but then hoarders are always close to trash collectors. Still, he had an ambivalent relationship to art every step of the way. Black Mountain was always on cutting edge, and he knew it. He reconnected with a classmate, Suzi Gablick, now a critic deeply skeptical of Modernism, and he photographed the shadow of an Upper East Side dealer, Sandra Gering, on a Walker Evans photograph in 1992. She could only have been flattered. Yet he left for the suburbs in 1948 and never looked back.

It was not just escapism. He still kept up with such artists as Félix González-Torres, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Christo—and they became his subjects, too, along with Albers with his cat. Johnson took a photo by the first of an unmade bed, nestling bunny ears on its pillow. He used the bunny as a signature and an alter ego. Nestling in bed, it placed him in the very midst of the avant-garde. Yet he had to wonder whether New York was still in touch with real life.

Evans and Jared Bark felt drawn to photo booths for their portrait of America, and Johnson must have felt the same. He may have preferred a cheap camera because it relieved him of the burden of contact prints and making choices. Yet it was also the camera of choice for most Americans. Did he favor movie stars to documentary photography? That was America, too. He liked to set up his collage in drive-ins and parking lots before shooting away.

It allowed a more capacious view of photography or America—one that could set Tab Hunter, the teen idol, alongside William Burroughs, the Beat generation writer. At the same time, it allowed Johnson a mask. He posed sheer strangers behind one. Overexposures and torn layer upon layer of collage created others. When he holds a blue crescent moon up to the sea, landscape becomes a mask as well. Both his obsessions, masks and movie stars, align him with Pop Art, and he adds bunny ears to Jasper Johns, too.

The curator, Joel Smith, quotes The Times in calling him "New York's most famous unknown artist," sharing his fascination with fame. Anyone wary of the Morgan's turn toward contemporary art and rediscovery should be suspicious. It also buys into Johnson's own claim to have begun a career in 1992, but do not believe that either. He had turned to photography in the 1950s, without the Kodak, but with the same titles and motifs. Maybe for him it was all a plea for help, like the word HELP on the underside of a boat. Packed into the small lobby gallery, his work has once again narrowly escaped the trash.

William Klein ran at the International Center of Photography through September 15, 2022, Ray Johnson at The Morgan Library through October 2.