Out of Fashion

John Haberin New York City

Early Diane Arbus and Paul Outerbridge

"My favorite thing is to go where I've never been." Maybe so, but once Diane Arbus had been there, she could not stay away.

She was not alone, either, in stepping out of fashion photography. Who knew that Marcel Duchamp kept a photograph by Paul Outerbridge pinned to the wall of his studio? Ide Collar shows a shirt collar, its open circle resting on a chess board, cropped at an ever so artful angle. First, however, Arbus.

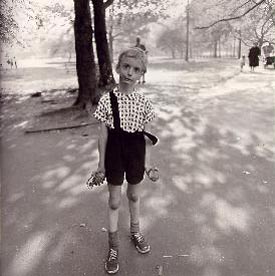

The Met Breuer exhibits her first years as an independent photographer—starting in 1956, the year she turned twenty-three. And it shows her returning again and again to the same disturbing New York. She heads for Mulberry Street and Central Park, but also the perpetual carnival of Coney Island, Times Square, and a "museum" of the grotesque, with a side trip to Disneyland. She goes to the movies and photographs the screen. Among the show's last images, a boy holds out a toy grenade in a near spastic grimace, as if caught between his aggression and inability to act. It is still disturbing, but six years before that Arbus encountered another boy, pointing his toy gun right at the camera and right at you.

She had already had enough, long before Mary Lum and a more upbeat photocollage of New York. She hated her work in the fashion industry with and for her husband—and indeed her first camera came to her at age eighteen as a present from Allan. The city as madhouse must have seemed the ultimate repudiation. It also laid the groundwork for her mature art. So she took to life on the streets and to disturbing performers, for their twin promises of hiding nothing. Only they turned out to be one and the same.

Where she had been

For Arbus a stage set extends to a boxing ring, a pool hall, a furniture display window, or a morgue quite as much as to the theater itself. She also goes backstage, like Edgar Degas, for performance in the making. Something of the same self-creation appears in the many male and female impersonators—or in a living room in Levittown, the very emblem of mass-produced suburbia, where a huge Christmas tree adds to the middle-class respectability of a magazine rack, sofa, and TV. Everywhere she goes, she looks backstage, for the intimacy of couples arguing, whispering, or dancing. Everywhere, too, she leaves it uncertain where backstage ends and the first act begins. A madman in an otherwise empty bar could be performing for no one.

Arbus lingers on that moment between intimacy and performance. When she photographs the movies, she captures the moment before a kiss or after a murder. When she takes to the streets, she allows a secondary figure to engage the camera, less like an extra than a potential replacement for the lead. It might be the passenger in a taxi, while the driver leans out to acknowledge the camera—or a man on the back seat behind a woman on a bus. With a barber shop seen through a confining doorway or a boy rising above a crowd, the real action is in the background. With the headstone at a pet cemetery for Killer, the action is decidedly past.

She lingers, too, on the moment between life and death. A gaunt hospital patient seems to be dying before one's eyes, her whiteness indistinguishable from the sheets. A woman raises her hands out of the water as if in one last desperate call for help. Both a boy and a girl step off a curb, as if into danger. Both a man and a woman hold a sleeping child like a New York Pietà. For Arbus even dying could be just a performance, much as for a razor blade swallower or a headless woman.

You may feel that you have had enough of this cabinet of curiosities even before you get there. The same museum's Arbus retrospective went into depth barely a decade ago, and my review then exhausted pretty much anything I can say. This selection of early work boasts of the Met's vast archive of the photographer, acquired in 2007 as a gift from her daughters. It also boasts of the Met's takeover of the former Whitney Museum, with a crowd pleaser and a frustrating but creative installation. It sets out rows of slim walls like floor-to-ceiling pillars, each wide enough for just one photograph, defying chronology or theme. They rise like human presences, much as for Arbus.

The curator, Jeff L. Rosenheim, also has a case to make. "In the Beginning" shows not just an artist's coming to be, but also what she had to leave behind. She liked the grain of prints from a hand-held camera, perhaps because it brought New York in artificial light closer to her images of the movies—blurred, multiple, or smearing outward with light. Yet she had to turn to the square format of a Rolleiflex for her later style's unrelenting focus. She liked what she found where she had never been, but she had to exchange the spontaneity of street photography or the artifice of institutionalized "freak shows" for collaborations with her subjects, much like Bruce Davidson also in New York, to the point that to speak of normal and freaks makes no sense at all. A back room holds a box of ten photographs that Arbus assembled in 1970, already a kind of greatest hits, so that you can see what she became.

Another room shows her returning to where photography had been in a different way, with predecessors and contemporaries. They include Walker Evans, Helen Levitt, and Louis Faurer with similar subjects—or Lisette Model (with whom she studied), William Klein, and August Sander with the creeps. They include the personal response of the "new documentary photography" of Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander in "America by Car," Robert Frank, and Mark Steinmetz. These make for a compact survey of photography, almost enough to normalize even Arbus. Still, the show's heart lies in the staggered rows of human presences, like ghosts, for a measure of how she differed. Just bear in mind that she could not make the strangeness of her art so vivid until she gave up the ghosts.

Stepping out of art

For some, Paul Outerbridge stands just apart from the mainstream, thanks to his work in color and commercial photography before either was altogether respectable, much like Joel Meyerowitz. He may seem to stand even further from Marcel Duchamp. Did the master of anti-art admire a beauty akin to formalism after all? Did he take it as an expression of his own high style and love of chess? Or did he empathize with Outerbridge as a challenge to art? Did he appreciate that, outside the platitudes of art, beauty comes with its share of unspoken constraints—much like a machine-made collar or the rules of the game?

Perhaps, but this was not the challenge of Dada. Rather it was the challenge of a photographer who, at least on the surface, got along just fine with fashion. The photograph, often (and understandably) misnamed Idle Collar, appeared in 1922 in Vanity Fair. Its readers would have known that Ide & Co. catered, as an early advertisement put it, to fashion's "latest edict." Now a show brings together his work for himself and others. With forty photos from over twenty years, it also dares one to determine which is which. Do not expect easy answers.

Commerce has often had an uneasy relationship with art and its struggle for independence, recognition, and respect. Think of big money in art now. Unlike Madame d'Ora before them, Arbus and Frank put fashion photography behind them as quickly as they could, while Cindy Sherman has subverted it, by "Fashioning Fiction." Richard Avedon made it his art, in portraiture, even if he could never quite wipe its veneer off a subject's face. At least Irving Penn tended to keep the two halves of his life apart. Not Outerbridge, who embraced them as casually as not quite intimate acquaintances.

He could serve as a pocket history of photography and photography's last century all by himself. At first glance, he takes some time to shed a devotion to fine art, before ending with parodies of commercial illustration that would do the "Pictures generation" proud. The very first shot, from 1918, looks left over from the previous century. Julia Margaret Cameron could have photographed his girl with long braids picking flowers out of the mist. Before long, he presents a kitchen table as A Study in Ellipses and a crankshaft as an emblem of modernity. This is formalism, but fully in the present.

He could serve as a pocket history of photography and photography's last century all by himself. At first glance, he takes some time to shed a devotion to fine art, before ending with parodies of commercial illustration that would do the "Pictures generation" proud. The very first shot, from 1918, looks left over from the previous century. Julia Margaret Cameron could have photographed his girl with long braids picking flowers out of the mist. Before long, he presents a kitchen table as A Study in Ellipses and a crankshaft as an emblem of modernity. This is formalism, but fully in the present.

In the very last photo, from 1941, a zealous father serves donuts to his son, who devours them just as eagerly. They share formal dress and exaggerated expressions that all but shout phony! They also share the perfect kitchen. A note above their heads breaks the illusion: "Gone to Bed / Prowlers Welcome / Mother." So much for fine art and advertising alike.

Naturally things are more complicated. Born in 1896, Outerbridge took up photography in the army before moving on to assignments from Vanity Fair and Vogue. Yet already the moves run both ways. In Paris, he got to know Duchamp, Man Ray, and Berenice Abbott while seeking more work from Vogue—which then led him to Edward Steichen. Steichen might have relished his view of the Brooklyn Bridge, in which one man faces the water while another faces away. The city, they say, has more stories to tell, and so does he.

Stepping into excess

He does in still life, which becomes his focus, as with that shirt collar. Over the course of a decade, it takes on a greater Surrealism without once losing its elegance. Eggs resting in a bowl give way to a single egg perched precariously on the point of a pyramid, itself cut by a triangle of glass. An upright piano becomes a study in shadows, surfaces, and silence. Outerbridge could have been the next Paul Strand but with a greater aversion to people. Objects are sexy enough on their own.

Still, nudes start to appear, if not quite in person. One from 1923 lacks a head and anything below the knees, while one from 1936 shimmers behind a curtain as Descending Night. Masks appear as well, and so does the masquerade. One mask rests on calling cards, as Fantasy. Another disguises a kinkier nude, posed against patterned wallpaper. One could mistake the mustache in a self-portrait for painted on, like Groucho's.

So, too, does color. Outerbridge adopted it from almost the moment it became widely available, before Ernst Haas and decades before William Eggleston, Eggleston's "Los Alamos," or Gordon Parks. He even boasted of it with a book, Photographing in Color in 1940. Art photography mostly disdained color. Yet it freed him to acknowledge something that already connected his art and advertising. Now people become explicit, and so do their desires.

Part of color's lack of respectability arose from the medium itself back then, lending it an unnatural saturation. For him, that suited perfectly an art of repression and excess. Desires emerge directly in packed shelves of canned goods and in a redhead with Hollywood looks and a cigarette. Her hair and lips stand out against the peacock patterns of her green silk and the garish yellow behind her. A Christmas ornament lies against a deep red wall as if bursting apart. The dark spikes beneath take a moment to register as ordinary pine needles.

Where did his true allegiance lie? It may not make much sense to ask, which adds to his modernity. He continued his dedication to art in, once again, an ad. A Cinzano bottle shares a still life with a timer, a half-folded yardstick, and a shining red ball. Outerbridge called it Kandinsky, as if it were abstract art, and he may not have been kidding. Then again, perhaps he was.

Could his apparent ease have masked a tension in his work all along? Maybe those still lifes became more and more surreal because he could not hide the tensions from himself. A whirl of colored glass from 1938 bears the title Political Thinking, as if he wished that even advertising could count as political art—or that political art could humble itself to advertising. In the end, his career comes full circle and to a premature end. First Robin of Spring returns to flowers that the girl might have picked in 1918, but now as a sensual array cutting off a roof and sky. He moved to California and pretty much gave up photography fifteen years before his death in 1958.

Early Diane Arbus ran The Met Breuer through November 27, 2016, Paul Outerbridge at Bruce Silverstein through September 17. Portions of this review first appeared in New York Photo Review. A related review looks at Diane Arbus in retrospective.