Myth Maker

John Haberin New York City

Amedeo Modigliani: Beyond the Myth

When the Jewish Museum titles a retrospective "Beyond the Myth," it sets an impossibly high standard. It takes a truly great exhibition—or a great artist—to take one beyond convenient fables. And yet both, too, have stories of their own to tell.

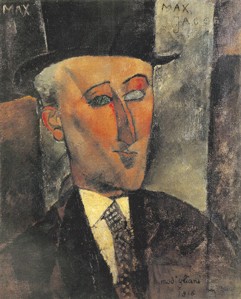

With Amedeo Modigliani, the museum sets itself an implausibly low standard as well. It claims the artist as, first and foremost, a Sephardic Jew. If that sounds like special pleading, it is. As one more outsider in a café society of outsiders, Modigliani shows hardly a trace of Sephardic customs, beliefs, or, dare I say it, myths. His few Biblical subjects allude, vaguely, to the New Testament. Perhaps my favorite of his portraits depicts, Max Jacob, a Jew from Brittany who had converted to Catholicism.

Can a show that reclaims an avant-garde artist for Sephardic culture seriously pretend to go "beyond the myth"? In practice, the Jewish Museum offers a reasonably enjoyable show of a wildly popular painter. Together with a show the year before of Elie Nadelman, it also asks tough questions indeed. What should one make of an outsider in the avant-garde?

But which myth?

"Beyond the Myth" sounds terrific, but which myth? Just for starters, one has the complacent myths of a prevailing culture. Modernism thrust in one's face the real-life underbelly of Paris—what Emile Zola had called Le Ventre de Paris. No wonder Picasso's whores may be said to have inaugurated modern at. And, sure enough, Amedeo Modigliani started his work in his new city, around 1910, with sketches after circus performers and other "low-life" entertainers. In his last years, from 1917 until his death in 1920, he painted nude women, with abundant eroticism and surprisingly little idealization.

On the other hand, again as with that Picasso, Modernism delighted in myths. Africa and the East supplied their share, of course. They offered artists a vision of nature, of a truth beyond the accumulated lies of Europe. They also offered new conventions, helping art to reconstruct the very idea of representation. They helped separate it from the illusion of the natural—in traditional realism or in life. And, sure enough, Modigliani first saw himself as a sculptor, with limestone heads in 1911 that adapt non-Western models.

Then, too, the avant-garde was among its own finest myths. The artist bared a soul, not to mention more earthly desires. That meant the immediate desires in Picasso's lovers and whores, as well as the universal ones of myths everywhere. From the moment that Les Demoiselles d'Avignon drew back the curtain, Modernism promised the real thing. Only what Pablo Picasso found in that brothel was a reflection of his own desire in a row of masks.

And, sure enough, the Jewish Museum wants to go beyond the myth of the avant-garde or a "Primitivism Revisited." That myth will not die easily, however—not when the artist reveled in it. Modigliani lived fast and died young, at age 35. He worked largely in poverty, giving up sculpture as war made its materials rarer and more costly. He settled into the bars and studios of Montparnasse, with a lover who killed herself. He had a funeral attended by all the right people.

All these aims must seem thoroughly incompatible. How does one get beyond the myth when the painter sought the myths—and lived one? How does one proceed when unveiling was the greatest myth of all? In fact, Modernism demanded that one keep incompatible ideas in one's head at the same time and still function. It singled out role-play, like a circus act or the act of a whore sacrificing her own desire to professional appearances. In perhaps his darkest and most truthful self-revelation, Picasso paints Three Musicians, with their art unheard and their only face their masks.

Ironically, the museum may well have a point about Modigliani, as the outsider among outsiders. However, the revelation can lie neither in the artist's traditional beliefs or in the purity of his art. He wanted no part of either one. Rather, it may lie in his ambivalence toward tradition or the avant-garde. Modigliani sells tickets today because he knew when to stop taking chances.

Blue noses

One could easily call this retrospective "Beyond the Lines." They wind around the block, even on a holiday weekend. I had known a little about Modigliani, as a respectable artist skipped entirely by at least one major survey text. I had never imagined Modigliani's popularity, but once inside I understood. He plays the bohemian in his art as well as in life, but he also plays it safe. He offers a Modernism for those not entirely comfortable with modern art.

By 1910, Picasso had long left the circus for the whorehouse. He had portrayed landscape as a factory set amidst a jungle, lovers as the barest trace of sensuality. He had attained the start of Analytic Cubism. Modigliani, who received academic training in Italy, keeps out of trouble. His circus performer spreads her legs, but her costume does not expose her sex. Drawings like this display his quick, incisive line at the expense of spatial and psychological complexity.

Picasso's sculpture breaks up vision into conflicting planes and appropriates objects from outside art. Constantin Brancusi turns the art object and its sculptural base upside-down. Not Modigliani. His totemic heads have all but identical, stylishly elongated features and a dignified reserve. Others sculptors deconstruct the boundaries between art and life and between cultures. Modigliani throws them all into art's food processor, without even the pulse.

The portraits show a growing confidence, but also a growing eagerness to please. Their vacant eyes and quiet expressions look lovely, but without much individual personality, intellect, anger, or humor. One remembers a dealer's elegant attire, a French poet's dreaminess, or a Polish poet's dashing hair and beard. They play their parts to perfection. Picasso had given Jacob, the adventurous art dealer, a high, bare forehead topped by a brutal shock of color. Modigliani gives him a top hat and tie.

The final nudes come nearer to a breakthrough. They show greater geometrization of the human form, but also some of the lumpiness of ordinary flesh. Yet even here the artist draws back. The poses show a knowledge of Henri Matisse and his Red Studio, but the execution looks further, to Paul Gauguin's woodcuts. Modigliani presents sagging stomachs and private parts as a matter of brute fact, but breasts never less than perfectly rounded. These women retain a very traditional, dual function, as real, sensual creatures and as tools in the hands of a male artist.

Modigliani's backgrounds approach abstraction, not because they dismantle realism or intrude on the subject, but because they stick to daubs of sober blue and maroon. In effect, he never quite outgrows Picasso's blue and pink periods. One remembers that, for most people, those cautious experiments still define modern art. To Picasso, too, the Italian adds a fashion sense closer to John Singer Sargent, in Sargent's watercolors or artist portraits, or to James McNeil Whistler. One wants to remember the avant-garde this way, as people who knew how to dress—or undress—for the occasion. Modigliani wanted to remember himself and his friends that way, too.

The Puritan that danced

But enough about sex and style. What, the Jewish Museum still wants to know, about his art? And what about his roots? The museum wants one to think of the transience of a population that left the Iberian peninsula for Italy and now Paris. However, that amounts to only one more step than for Picasso himself. And not once in the show could I see a specifically Jewish influence.

The museum associates the universalist aspirations of assimilated Jews with Modigliani's turn to Cycladic sculpture and the intellectual avant-garde. However, that defines his heritage in terms of his lack of interest in his heritage. The museum even sees repressed longings in the coolness of his portraiture. That sort of reasoning should keep museum-goers in therapy for years to come.

The museum has made a similar case before, in retrospectives of such progressive artists as Camille Pissarro, Chaim Soutine and Soutine still life, George Segal, and Chantal Akerman. Besides, the case stands at the very core of the museum's mission. Indeed, the institution exemplifies its own argument. It has a dedication to Jewish artists and Jewish collectors like the Sassoons as Jews long before Jonathan Horowitz, as well as to the intellectual traditions and the sense of difference that helped create Modernism.

No matter how pressing that case, the paradox of the outsider in the avant-garde will not go away. Jews have contributed more than their share to modern notions of art, science, and, I like to think, social justice, even when those ideals have had an ambivalent relationship to tradition. The paradox holds, too, even when the avant-garde has had its share of anti-Semitism. The list could start with Picasso's greatest fan and a Jew herself, Gertrude Stein.

Perhaps Modigliani's real relevance lies in that very paradox. Maybe the museum had a case despite itself—not in the artist's daring to exceed myths, but in his hesitation on the brink. As an assimilated Jew myself, I have written about my refusal to define myself in terms of a religion's practices, along with an inescapable awareness of how others may define me. I have written, too, about my unwillingness to believe, as well as the outsider perspective that leaves one questioning at times the beliefs of mainstream America. I wish to be the last to generalize about Judaism and Jews, while understanding how much I love inquiry and generalizations.

I thought of Elie Nadelman's retrospective at the Whitney, just one year ago. Nadelman's early sculpture combines Classicism with the uniformly demure, downcast eyes of Victorian femininity. He embraces American folk art, in sculpted wood, with all the severe clothing and high cheekbones of New England Puritans. Yet, in his most memorable images, the Puritans dance. Modigliani has the same Classical instinct in sculpture, the same blank eyes in his portraits, a dedication to modern art, conservatism when it comes to modes of representation, and a hesitant but heartfelt sensuality. It made him something memorable after all—the ultimate society portraitist for a society on the edge.

"Modigliani: Beyond the Myth" ran through September 19, 2004, at the Jewish Museum. "Elie Nadelman: Sculptor of Modern Life" ran through July 20, 2003, at the Whitney Museum of American Art. A related review looks at "Modigliani Unmasked."