A Copy of a Copy?

John Haberin New York City

Sturtevant and Yasumasa Morimura

Sturtevant did not make copies. They just look that way.

Does that make them mere simulations of copies? And does that mean that a copy of a copy is an original? Does it matter that the artist is very much a part of her works, and does that make them all the more original? Or is Sturtevant then just copying another artist's presence? A retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art is filled with puzzles. And maybe the biggest is what puzzles have to say about modern art.

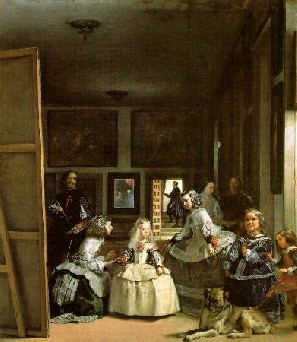

As a postscript, multiple photographs after Diego Velázquez may hold a clue. Is a copy a reenactment of the original, as in a theater? To produce a copy of a work of art is to stand in for its subject matter, one might argue, like the sitter for a portrait. Only no one sits for a portrait in Las Meninas. No one has time. Just ask Yasumasa Morimura.

Double negative

Actually, one must take Sturtevant at her word that she was not making copies, and one is free not to. She earned a reputation in the early 1960s as a copyist—the woman making Warhols. One will have seen it all before, even if one has never heard of her. Just in case one fails to identify the originals, her titles always do. The show's fifty works include flowers after Andy Warhol, numbers and a target after Jasper Johns, a crying women after Roy Lichtenstein, spaghetti after James Rosenquist, and image after image after Marcel Duchamp. They include, as one critic described it, "the worst Frank Stella I have ever seen."

The curator, Peter Eleey with Ingrid Langston, imagines that any of the artists she targets would have felt the same way when it comes to his work. (I say his, because almost all are men.) And in no time the puzzles begin to multiply once more. If they are copies, then why does she retain the marks of her hand? If they are only copies, then does that make what they copy the originals? But then why do they draw so often on artists who flaunt found objects and reproductions?

One must take her word about a lot of things. Born in 1924, she styled herself Sturtevant (her married name) because, she said, she liked its bluntness—but then that hid her (first name Elaine) behind a mask. She valued Pop Art for its immediacy, but then conservative critics like Robert Hughes have seen in Warhol's generation the death of emotion in art. Artists then all had their own ways of surprising a viewer with a bold surface while keeping a certain distance. Johns likes to say that he cherishes his found imagery for its own sake, while Lichtenstein typically painted Ben-Day dots freehand, like his own copies after reproductions. Sturtevant began by slicing tubes of paint and turning them inside out.

The retrospective, "Double Trouble," has no shortage of redoubled images and double negatives. That could equate with positives, but do not be too sure. Her selections seem like a survey of their time, but she denied that as well. Rather, they reflect a shared engagement. Robert Rauschenberg encouraged (and posed naked with) her, and Warhol loaned her a silkscreen, as if welcoming her into his talent show. It would be great, he declared, if more artists took up his silkscreens so that no one would know who made them.

Is reusing a silkscreen the same as copying anyway? Sturtevant also performed a dance after Yvonne Rainer, and one can see all her work as a reenactment—or what Eleey calls a "total phenomenon." She labeled one sheet a "working drawing," as if caught in mid-act, and adopted not just the images of others but also, badly or not, their methods. Nor was she content with plaster underwear after Claes Oldenburg. She had to open her own East Village "store" a few blocks from his as well. Apparently he did not like the competition.

She also placed herself within the image. She is the nude in a motion study after Eadweard Muybridge and the nude descending a staircase after Duchamp. For a further puzzle over presence, there she is dressed after Duchamp. She is the one, too, dripping animal fat after Joseph Beuys. Another performance after Beuys turns her into John Dillinger, and a photo collage after Duchamp places her in a wanted poster. The artist is both here and at large.

The total work of art

Maybe she was right about not copying, for that privileges object over experience. Sturtevant refused to say that she did the best she could, because that would imply that the differences matter—and so, then, would the status of the original. Still, her claim leaves out far too much history. One can think of everything as already a duplicate, but on one condition: there is no unique sense of duplication. Artists all have their own use for the copy, as part of the continuing puzzle of modern art.

For Duchamp, it sometimes meant the end of art and sometimes its structure. For Johns, it nurtures surfaces, so that one can never disentangle concept and expression. For Pop Art, it effaces the difference between high and low art as well. For the "Pictures generation," it became a political act and, for Sherrie Levine, a feminist one. For Cindy Sherman, it evokes a fiction. For the Young British Artists, it threatens to dissolve into cynicism.

For Warhol, its meaning has been subject to debate every step of the way, starting well before Hughes. Arthur C. Danto saw Warhol's reproducibility as a clue to the definition of art. Rosalind E. Krauss then pushed the assault on the "originality of the avant-garde" back to the very birth of Modernism. Fair enough, but Warhol found joy in art as collaboration, just as when he welcomed Sturtevant. Conversely, he found images of death at the heart of American culture. His choices might not even be all that indistinguishable from the original after all.

Maybe Sturtevant opens the way to a philosophy of art, or maybe she short-circuits one. That could be why her retrospective can sound much more interesting than it is. It might not even be her retrospective. She died shortly before she could see it, leaving the curator to make the final arrangements. If art is the totality of its making, the retrospective is his total work of art. To add to the puzzles, she herself grew restless with tossing off Warhols.

Could a change in her art explain her denials? She must have felt that she had hit a dead end, for she quit making art for more than a decade. (Try not to object that there she was still copying Duchamp.) When she returned, she looked for newer models that fit her story, like Robert Gober, Félix Gonzáles-Torres, and Keith Haring—but not only that. She exhibited half a dozen versions of Duchamp's Fresh Widow, or French windows with their glass painted black, so that none of them could be the original or the copy. She silkscreened Marilyn Monroe in black, after a Warhol that never existed.

Videos depart further still from her formula. A multichannel installation runs through her past choices and more, while a single channel channels Pacman. A dog runs continuously along the entrance wall. She could be reaching that much harder for immediacy, but no longer finding it. She could have reached the culmination of a fifty-year project—or finding that it was a lie all along. Then again, she had never believed in innocence.

Standing to make a painting

Oh, surely the king and queen in Las Meninas are sitting for their portrait, with Diego Velázquez boldly looking out from behind his easel to paint Juan de Pareja—or maybe not. Seen from the waist up in a mirror, they could be standing erect for their portrait or just looking in like you and me while the artist prepares his enormous canvas for the work at hand. He might be preparing for their daughter, Margaret Theresa, already at the actual painting's center. Perhaps the princess, or infanta, is still to take her place, once half a dozen court attendants and a more handsome dog let go. A man on the stairs behind is caught forever in a brighter sunlight on his way in or out. Velázquez himself is in motion, his brush raised with a flourish more than equal to his mustache, for his only confirmed self-portrait.

The illusion of an instant demands the patient artifice of an illusion. Velázquez navigates with ease the royal circle and the Alcázar, the Muslim fortress that became a royal palace just as Madrid became the capital of an empire. He uses a mirror as a painting within a painting quite as much as Jan van Eyck two hundred years before. That richly dressed couple stood for their own double portrait of a marriage. Michel Foucault went so far as to take Las Meninas as an emblem not just of art and illusion, but of the power of western eyes. As he wrote in The Order of Things, "We are looking at a picture in which the painter is looking out at us."

The illusion of an instant demands the patient artifice of an illusion. Velázquez navigates with ease the royal circle and the Alcázar, the Muslim fortress that became a royal palace just as Madrid became the capital of an empire. He uses a mirror as a painting within a painting quite as much as Jan van Eyck two hundred years before. That richly dressed couple stood for their own double portrait of a marriage. Michel Foucault went so far as to take Las Meninas as an emblem not just of art and illusion, but of the power of western eyes. As he wrote in The Order of Things, "We are looking at a picture in which the painter is looking out at us."

Morimura, too, will have others looking, but he loves most of all looking at himself. The Japanese photographer first posed as Philip IV of Spain in 1990. Now he steps in for the entire cast. The characters look dressed for a costume party, the greater their finery and the uglier their faces their better. One photo reveals the unseen canvas, with a maid of honor or perhaps even the infanta as a little more than a troll. I cannot swear that Morimura plays all the roles, but he flaunts the digital overlay.

He keeps adding and removing portraits—and not just within the painting. He also toys with its place in the museum. In one photo the painting gives way to dark architecture much like its own, while in another it remains empty. Now and then people stroll through the Prado to look at it. They include all the actors at once, give or take the dog, and the photographer dressed only as himself. At least I think so, for one sees him from behind.

Does he have all that much to say about artifice or art? If the chance of female roles again recalls Cindy Sherman, a back room has smaller self-portraits in black and white like her Untitled Film Stills. As a show of hers put it, he is "Fashioning Fiction." Morimura also poses, Spanish figure by figure, apart from the painting. Still, he is relishes more than penetrates fictions, much as he relishes his macho. The entire series sounds like a boast, not to mention pretentious, as Las Meninas Renacen de Noche (or "Las Meninas Reborn in the Night").

He does not challenge the museum, because he clearly thinks he belongs there. This is not what Ilya and Emily Kabakov called "The Empty Museum"—or even Las Meninas. In a video reenactment by Eve Sussman, the screen froze into place, and a busy moment had become an eternity. Morimura himself wants, as one subtitle has it, to be Finding a Tiny Waiver in Silence. In practice, he has no patience for silence, but one may as well enjoy the buzz. Like Velázquez in yet another interpretation, he is looking at you.

Sturtevant ran at The Museum of Modern Art through February 22, 2015, Yasumasa Morimura at Luhring Augustine through January 24.