Consider the Alternative

John Haberin New York City

The 2022 New York Art Fairs I

The New York art fairs will never again be as they were, but who cares? Even after Covid-19, there are more than enough to go around. Sure, the Armory Show and other March fairs have left for September—including, irony of ironies, Spring Break. And here you thought that cutbacks in art after Covid-19 had made fall openings halfway manageable.

Yet Frieze is back the last weekend in May, chastened and with more than its share of galleries online. Who would dare predict the future? TEFAF is back, too, two weeks earlier at the Park Avenue Armory, boasting more and more elaborate antiquities, oysters on the side, and, now and then, some seriously upscale painting. The sense of a single, perpetual global art fair is more inescapable than ever. Even self-curated stragglers feel the pressure from multiple cities. Allow me, though, to start with the fairs that bring real alternatives to New York—including the Future, the Independent, NADA, and Volta.

Collectors and commuters

The Future has its second year in Chelsea, and one might expect only the worst. It has given up the post-industrial classic Starrett-Lehigh building in favor of a new event space, Chelsea Industrial, two blocks away. Last time out, it seemed little more than low-end business as usual. Yet the modern, maze-like space seems to suit it, and the overcrowded layout for now adds to its energy. If the small booths preclude mammoth works, it gives the illusion of something larger. Five design studios come together as "Alien Days," and their rounded forms could almost be nineteenth-century lab vessels or space travelers from (yes) the future.

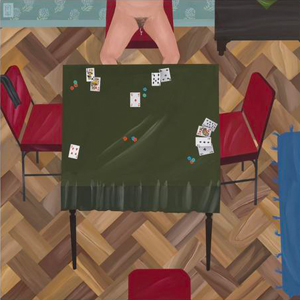

It may just be my prejudices coming together, but I took special pleasure in the very few New York galleries and their abstract art. Bethany Czarnecki (with Massey Klein) could be pouring paint, were the apparent pours not so tightly packed and hard edged. Traci Johnson, a young African American with Morgan Lehman, works with rugs that give intense colors the shaggy textures of her own bright green hair. Both galleries have a second artist who merges deep and shallow space as a field for what might almost be alien life—Nevena Prijic, a Serbian artist, and Nathan Randall Green. Much else is just garish, but Beers, a London dealer, gets realistic. Trompe l'oeil interiors by Gori Mora, a Spanish artist, have the sheen of oil and the cut-off edges of sunlit rooms by Florent Stosskopf from France.

I-54 is back after a year of pandemic and, it must think, closer to where it belongs. It has moved to Harlem Parish church for its art from Africa and the African Diaspora. With just two dozen galleries, its scope is modest but its aims are bold. Its flat fields of ample black and color are no longer groundbreaking or always compelling. They apply to pillars by Thandiwe Muriu (with France's 193) and to portraits by half a dozen more—which is not to dismiss other approaches from photography to quotes from art history. In context, though, they speak to boldness and blackness.

The Independent is back, too—back overlooking Tribeca after a year by the Governors Island ferry. Its four floors encourage an unpressured stroll. As ever, it is a true class act, unspoiled by insufficient talent or too much money. It has such upscale dealers as Marianne Boesky and Alexandre, an old survivor like P.P.O.W., and a long-time backer of outsider art in Andrew Edlin. Its heart, though, lies in the downtown galleries that led the way to today's climate. They make it a more New York-centric fair than in its first years at Dia:Chelsea, but not to the exclusion of others.

Right off at Maxwell Graham, I encountered commuters or simply those lost in a city, and that city could be anywhere. Sarah Rapson sets them in what might otherwise be scraps or steps toward a painting, as well as on video. Painted figures by Trude Viken, from Oslo (with Fortnight Institute), and David Shrobe (with Monique Molish) could be caught in their own Walpurgisnacht. They are enjoying every minute Jessica Jackson Hutchins picks up the current interest in ceramics and assemblage, with hints that her figures, too, have an independent lives, while Joan Nelson (also with Adams and Ollman) derives the eerie light of her landscapes from paint, glitter, and milk. Even so, she cannot approach the seeming sun bursting out at the center of sculpture of thread, by Michelle Segre (with Derek Eller).

Rachel Eulana Williams with Canada, another downtown survivor, sticks to abstraction while, she says, unbinding it from its stretcher. She also adds strips of linen to her tondos, binding them closer to sculpture. African Americans for Roshin Finley (with Tilton) are young but survivors as well. Finley's loose brushwork in black and white celebrates them as individuals while leaving them in shadow. Nudes by Janice Guy (with Higher Pictures), in photos from the 1970s, let down their guard, too. They are self-portraits, though, camera in hand, and their evident posing suggests how Cindy Sherman developed her own act back then, between the constraints of a budding artist and the movies.

The real thing

If the Independent is an idealized gallery tour, NADA is the real thing, a tour of the workaday galleries that keep things alive. While only a few members of the New Art Dealers Alliance are new, they bring something new to the table year in, year out. With that kind of consistency, quite a few are from New York and LA, but with some interesting exceptions. Eli Ridgway brings James Chronister all the way from Bosman, Wyoming, to evoke dense woods in white on black. Voloshyn had a still longer journey to the booth right next store—from Kyiv in Ukraine, where art for Lesia Khomenko is not the only contested ground. It exhibits silhouettes of combat and young men standing by a wall, at ease but hardly at home.

It has been a bit since NADA held a fair, apart from a room apiece for just some of its members on Governors Island, in the decrepit officer's housing of Colonels Row. Now it can invite more than a hundred to an East River pier, where Art on Paper holds court in September. Now it must focus on what fairs do, which is to move merchandise. It has set out floral arrangements of "Oriental Opulence" and "Tropical Paradise," while a performance space hints at alternatives to business as usual. As I passed, a man appeared to be doing a stand-up act, while chess players, with backing from software companies, were "defining the future" of the game. Almost everyone else, though, sticks to painting.

Lefebve & Fils, a Paris gallery, supplies duly fashionable ceramics by Molly McDonald and Leah Remini, in the shape of a iron and flames. Still, even Bitforms, the new-media gallery, must rein in its preference for interactive art. Auriea Harvey treats the moving image as abstract painting. With so many group arrangements of gallery artists, it is hard to single out anyone, much as I admired brooding portraits in saturated color by Anthony Iacono or abstraction in motion by Tracey Thomason (both with Marinaro), coarsely painted spaces by Bessie Harvey and Thomas Dillon (both with Shrine), images of protest by Sheida Soleimani (with Denny Dimin), and more. I am not sure what geometric abstraction by Alex Heilbron (with Meliksetian MB Briggs) has to do with the female body or how sunlit landscape and still life by Anna Valdez (with OCHI) show the influence of René Magritte, but their paintings enliven booths to themselves. And all praise to those who can afford only half-sized booths around the fair's edges for hanging in there, whether it works or not.

"A solo booth helps you stand out in a crowded field." In the inevitable puff piece in The New York Times, a Berlin dealer explained his why he went for one at Frieze. But could the same formula make an art fair stand out as well? It sure did when Volta made it a requirement at the fair's debut in 2008. Not any more. In its new home in the former Dia:Chelsea, it feels like just another bad day in the galleries—pleasant enough, but a good excuse to hurry through and hurry home.

Not that its requirement became the norm, although Frieze in its former space had a whole section of solo booths, and some dealers do stand out for having one. The seemingly perpetual art fairs simply took the competition in stride and rendered it obsolete. Volta had looked good not just because solo booths show artists to advantage, but also because they gave the show the feel of an actual gallery tour at its best. By 2011, though, Volta was a "sister fair" to the Armory Show, on adjacent midtown piers, and in no time the alternatives had snatched the best art away. Now I could count only two or three of just under fifty galleries as New York must-sees.

The requirement is gone as well. Muriel Guepin stands out by a focus instead on artists who treat paper has painting or drawing in relief, including and Antonin Anzil and Anna Kruelska. Otherwise, often enough as solo acts, one has just what one might expect and fear—a bit of glitter here, a Jean-Michel Basquiat imitation there, ever so hasty realism and watery abstraction everywhere. I have a weakness for the last, so I can single out Rachel Krieger and her hints of landscape with Susan Ely or Jakob Kirchmayr (with Vienna's Galerie Ernst Hilger), but no matter. If one also has to put up with dog pictures, and if the otherwise admirable African American portraits look like commercial posters, so be it. The three-story space is as hospitable as ever, and one can overlook the irony that a true alternative, the Independent, began there as well.

Thinking big

As in past years, a Noho gallery, Zürcher, restyles itself for fair week as Salon Zürcher, with exclusively women. Now that it has abandoned placing them with New York dealers, the pretense of a fair is harder to maintain. Still, the sheer variety of approaches to abstraction is impressive, and so is the gendered premise. Fridge as a fair, with its refusal of booths in favor of walls of painters, is a still harder illusion to maintain. It has returned to a storefront gallery on the Lower East Side and, nearby, just plain storefronts (not excluding a juice bar) for its floor to ceiling hangings. Enthusiasm is just what fairs so desperately need, but it cannot make up for a lack of purpose or, dare I say it, taste.

For all the virtues of alternative fairs, Frieze wants you asking for more. This, it wants you saying, is what art should be, all inclusive and larger than life. If the two are incompatible, hey, art can do anything. For the second year running, it has moved from Randall's Island to more modest quarters at the Shed, in Hudson Yards. This is, after all, the city's most overpriced real estate. It is, though, far more inclusive than you might expect, and thinking big pays off.

It is still an art fair with the usual pretension and redundancy, but again it asks for more. It has the usual wealthy suspects, but also its "Frame" section for emerging artists, meaning halfway affordable space for emerging dealers as well. True, this is the tackiest work on any of the fair's three floors. (Dead Cowboys anyone, from Marsha Pels with Lubov?)  But nearby booths add such downtown stalwarts as Miguel Abreu, Canada, and Rachel Uffner—with the crisp but intimate interiors of Anne Buckwalter and carved wood flush with paint by Bianca Beck. A.I.R., the all-women collective, plants trees for action on climate change.

But nearby booths add such downtown stalwarts as Miguel Abreu, Canada, and Rachel Uffner—with the crisp but intimate interiors of Anne Buckwalter and carved wood flush with paint by Bianca Beck. A.I.R., the all-women collective, plants trees for action on climate change.

Does the next floor use much the same entry space to promote designer clothes? Never mind, for the fair is big business. True, it cuts back once more to just sixty-odd galleries, with more online. It could easily have packed in more, but the fair's director calls it a matter of respect and an "ethos." If that has you smirking, it allows for monster booths and time to get to know them all. Fourth-floor windows provide views of galleries below as well. The Shed's regular exhibitions could learn something.

Alexander Gray, not often associated with African Americans, devotes its space to Melvin Edwards and Lorraine O'Grady, along with Harmony Hammond. Sarah Sze (with Victoria Miro) breaks a massive black disk on the floor into pieces, as if continental drift had appeared overnight—and that still leaves room for Stan Douglas, Yayoi Kusama, and Alice Neel. Fast-paced, machine-like abstraction by Alex Hubbard (with Vienna's Eva Presenhuber) makes a spacious niche for clay (well, bronze) pigeons by Ugo Rondinone. Even a nonprofit, White Columns, goes upscale, with such artists as Georg Baselitz, Jeff Wall, Al Held, and Isamu Noguchi. Single-artist booths benefit from the space still more. Albert Oehlen uses a vending machine, with a free (and disgusting) mix of tea and coffee, to lure visitors, but others put a more serious face on serious art.

Carol Bove (with David Zwirner) uses an orange wall and an artful arrangement to convert her crushed orange metal into an installation. Yet it retains the tactile modesty of crushed paper. Liam Gillick (with Casey Kaplan) stacks rods of color after Donald Judd, with cumulative power. Eamon Ore-Giron places simple elements in symmetry on large fields of color, for murals as icons. Joan Snyder (with Frankin Parrisch) may seem small and delicate by comparison, but she is keeping alive a great age of abstraction. As always on fair week, money talks, but this once it speaks for others.

These fairs ran the second and fourth weekends in May 2022. I leave the AIPAD Photography Show to a separate article. Related reviews report on past years, the now departed March art fairs, claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19, and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" And do not forget the 2022 Armory Show and others in the fall art fairs, spring 2023 art fairs, and fall 2023 art fairs coming up.