Modernism on the Cheap

John Haberin New York City

As with so many jaded men, almost his only pleasures were in . . . gluttony. . . . His table offered up a doubly luxury, that of its contents and that of its container.

— Balzac, Le Père Goriot

Martha Rosler: Meta-Monumental Garage Sale

After The Scream: The Modern in 2013

Museum Tower's amenities, per its real-estate agents, include "hotel-quality" doormen, a concierge, a fitness center, a meditation room, and wine storage—but not, alas, a garage. For just two weeks, though, the museum beneath the luxury condo is having a garage sale, thanks to Martha Rosler.

Museum Tower, of course, is a towering condo that owes its prestige to its location, through the very heart of the Museum of Modern Art.  Rosler has staged her garage sale as performance art many times before, starting in 1973, but never with a more chilling contrast to its surroundings. While the tower rose as part of an earlier redesign, in 1983, it became newly emblematic of the Modern in 2004, when Yoshio Taniguchi made over the architecture. The museum had grown, but with the vast meeting spaces of a midtown hotel—and less and less care for art. With Rosler and the loan of a famous image by Edvard Munch, it is again time to ask about the commercialization of a great institution. I want you to scream.

Rosler has staged her garage sale as performance art many times before, starting in 1973, but never with a more chilling contrast to its surroundings. While the tower rose as part of an earlier redesign, in 1983, it became newly emblematic of the Modern in 2004, when Yoshio Taniguchi made over the architecture. The museum had grown, but with the vast meeting spaces of a midtown hotel—and less and less care for art. With Rosler and the loan of a famous image by Edvard Munch, it is again time to ask about the commercialization of a great institution. I want you to scream.

Black Friday at MoMA

Make that Meta-Monumental Garage Sale, for in the nearly twenty years since Martha Rosler first invited the public into a museum for shopping, it has never been bigger. On opening day at the Modern, just in time for the holidays, one could choose from LPs, books, jewelry, a foos ball table, (um) artworks, and a station wagon. (Rosler insisted on a car.) Used clothing hangs flat against the high walls of MoMA's atrium, like a more practical version of those tapestry maps of the world by Alighiero Boetti barely a month before. Had the artier versions already sold out? Judging by the paltry attention to the permanent collection upstairs, as you will see in a minute, one might think that much of it had as well.

Did not see what you wanted? No matter. The artist has cartons more on hand to replace sold items, so much that she has had to turn things away. Still more on opening day was in New Jersey, awaiting cleaning and fumigation (not, I should say, thanks to Museum Tower's laundry services), including the artist's family albums. And rest assured it is a thorough cleaning. A chalkboard inadvertently lost the inscription Yard Sale in the process.

She can tell you more while haggling with you, because she is present every day. It is no accident that the curator, Sabine Breitwieser, runs MoMA's performance art program. Still, one can hardly help seeing an installation—one that embodies the ideal of art as object at that. This art object just happens to be cash only, with no returns and no guarantees. Rosler priced everything herself, on those quaint tags attached by string, and prices seemed eminently fair to me. That alone sets her apart from much of the art world.

The old line about "commodity fetishism" has its ugly side. Karl Marx introduced it in Capital to nail the change from simple production and use to buying and selling—to acquisition and to objects at the very center of the "social relation between men." The idea took on new life in the twentieth century, with critics who looked first and foremost at the culture of capitalism, with terms like the "society of the spectacle." I could protest that their postmodern talk about fetishes and desires skims past people who can barely meet their basic needs. You could reply that it is precisely those who cannot afford a second or third home who most see themselves in the little they do collect and treasure. Either way, though, the idea seems all too appropriate for art now.

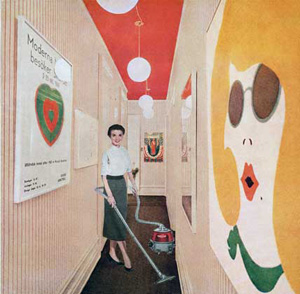

When Rosler held her first garage sale at UC San Diego, she could hardly have imagined what museums and other collectors put a value on today. The atrium may not exactly welcome art, but it sure channels crowds—right past the museum's bookstore. When MoMA's 2004 expansion created it, it also (The Times reported) added "the Brancusi of loading docks" to Museum Tower. Rosler's work can seem tendentious, including this one, compared to many women in Pop Art (and you can see her memorable contribution above) or even the overt irony of the "Pictures generation." Then again, back in 1973 admirers of Herbert Marcuse attacked her (seriously) for turning over a museum to sales. Little did they know.

For all that, the installation has an old-fashioned idealism, very much in line with the often dated technology on sale. It means to foreground the nature of capitalism, but also the values inherent in a yard sale of host and community, just as the "garage" in "garage band" implies a raw sincerity. One could question that populism, too, in a country where even much of the left has never really embraced an activist government rather than anarchy, but the idealism, too, feels just about right for art. Rosler sidesteps questions about where the money goes, because she wants the work to be about not charity, but desire. She delights in a woman who, when the garage sale occupied the basement of the old New Museum, browsed for an hour and promised to come back sometime to look at art. Now, art that tries to limit its meanings has a serious problem, but it makes for a great story.

Want to scream?

There was something reassuring about the line to enter MoMA's permanent collection, especially since, membership card in hand, I could bypass it. True, many come mostly to see Vincent van Gogh and Starry Night—and now the loan of just one of four versions of The Scream, a pastel at that. Rather than devote a room to Edvard Munch, with companions and contrasts, the Museum of Modern Art has people wait where they most easily fit, just outside the galleries for all of modern art. Inside, I had to wait anyway, even midweek in peak season, behind a sea of bobbing heads waiting to snap the work's picture with a cell phone, like a boyfriend or girlfriend on vacation. No doubt both the photographers and the art were, after all, maybe not on vacation but on their first visit to New York. I wanted to scream.

Still, they had come to see some of the best modern art anywhere, in the institution that did so much to define modern art and to create a public for it. One could easily forget the permanent collection, and on way too many visits I had. There is always another exhibition not to be missed, like the origins of abstraction, postwar Japanese art, and political architecture now, and Edvard Munch in pastel turns out to have the shocking natural and unnatural light of Post-Impressionism. Since MoMA's expansion, there have been an unprecedented number. Coming up the escalators, often scrambled as in a department store so that one has to walk around from the down escalator to avoid going back up, one gets some mammoth works as it is, without so much as entering the galleries. Within, there is space for more and more displays from more and more departments, with photography or architecture no longer a side show—space for seemingly everything but painting and sculpture.

Still, they had come to see some of the best modern art anywhere, in the institution that did so much to define modern art and to create a public for it. One could easily forget the permanent collection, and on way too many visits I had. There is always another exhibition not to be missed, like the origins of abstraction, postwar Japanese art, and political architecture now, and Edvard Munch in pastel turns out to have the shocking natural and unnatural light of Post-Impressionism. Since MoMA's expansion, there have been an unprecedented number. Coming up the escalators, often scrambled as in a department store so that one has to walk around from the down escalator to avoid going back up, one gets some mammoth works as it is, without so much as entering the galleries. Within, there is space for more and more displays from more and more departments, with photography or architecture no longer a side show—space for seemingly everything but painting and sculpture.

The old building came as a headlong rush of surprises, as Michael Kimmelman has argued, including what one thought was familiar. Now one must settle for a single odd drip painting from Jackson Pollock and a small black painting from Willem de Kooning. Even a show devoted to Abstract Expressionist New York had no space for Janet Sobel, maybe the first drip painter, in a time of unprecedented concern for women artists and outsider art at that. It hardly helps that MoMA has turned several rooms over to Trisha Donnelly as curator, for the first ever intrusion of its fine "Artist's Choice" series into the permanent collection. And while the old building's history ended sooner, the selections do not seem all that diverse or contemporary now. They also do not look more contemporary—or at least more relevant.

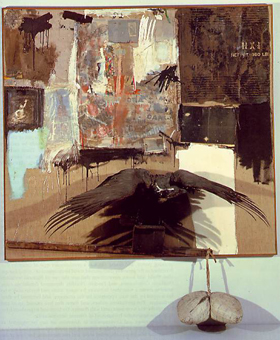

Rather, they look lost, under brighter lights reflecting off brighter ceilings in taller rooms. Barnett Newman in Vir Heroicus Sublimus seems neither heroic nor sublime. The gift of Canyon, by Robert Rauschenberg (from the estate of Ileana Sonnabend) with the unforgettable Rauschenberg stuffed eagle has reunited three major combine paintings, but they are too far apart to appreciate the reunion. Recent art, too, seems reduced from provocation to grandeur, like the scraps of personal history from Sigmar Polke or Joseph Beuys (although he was caught up in mythmaking all along). I had returned soon after Thanksgiving with a friend who had known this history ever so well at second hand, and I kept having to apologize. No, New York is not this safe, old, and out of touch, honest.

In an art scene with bigger and bigger stakes, museum architecture keeps asking for the same reception, as what Michael Kimmelman calls "buildings as baubles." As with the New Museum, critics cheer, and then the cheer wears off as the boxes look emptier of their gifts. I take pride in that I dissented from the first, but it says something that MoMA took a double hit in 2011 from The New York Times (not that anyone is asking why a museum this popular charges such high admission prices). I know the old is not coming back, like those long afternoons alone with Monet's Waterlilies that taught me modern art—and for good reason. Art is caught between the promises of commercialism and democratization, and not even a "garage sale" in the atrium can escape them. The problem is not in a much-needed challenge to the official history, but in not being able to articulate either the challenge or the history.

When did Modernism end, and did Postmodernism kill it or keep it on life support? Can one excuse the curators, faced with the wasted space and the sheer fact of MoMA after Y2K? Maybe, as part of the "postmodern paradox," one cannot disentangle the choices. Taniguchi's architecture treats Postmodernism as the culmination of Modernism, by making museum white cubes into a luxury chain hotel. More can be done, but it will ask more and more from the curators to stake a challenge. Maybe a flash mob as performance art should gather around the Munch and scream.

Martha Rosler's "Meta-Monumental Garage Sale" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through November 30, 2012. Edvard Munch paid a visit through April 29, 2013, "Artist's Choice" with Trisha Donnelly through April 8. Related reviews look again at Edvard Munch and at Rosler and other political art in 2008. As noted, other articles treated the museum renovation in 2004, a year later, and in 2011. A related review looks at Martha Rosler in retrospective.