Never Such Innocence

John Haberin New York City

Joel Sternfeld's First Pictures and Jill Freedman

A few photographers change how one looks at photography. Fewer still change how one looks at America.

Some, mostly journalists, do it with a moment—a death at Kent State or a kiss in Times Square. Some, like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans in the Depression, have captured an era. Most, though, have to settle for smaller changes. Joel Sternfeld, for one, documents not so much history as uncertainty. He describes an America somewhere between peace and violence, calm and anxiety, a national identity and an unholy mess. He called his breakthrough series "American Prospects," suggesting both multiple points of view and a hesitant future.

Speaking of change, how did he become Joel Sternfeld? An exhibition of "First Pictures" takes him from 1971 to 1980, the year that "American Prospects" had its first gallery showing. It finds him moving from place to place, before tackling a theme as large as America. It also finds a decade unsure whether it had left behind the turmoil of the 1960s or institutionalized it. It finds a decade, too, in photography—between searching for America and staging it. And, as a postscript, it makes an interesting contrast with the more journalistic but seriously loaded perspective on some of those same years, from Jill Freedman.

Watching grass grow

In 2000, Sternfeld still exhibited at Pace in midtown, but he came to Chelsea to photograph the High Line. The neighborhood was in quite a transition, too, although the blue chips had left Soho and staged a Chelsea arts walk three years before. "Walking the High Line" seems uneventful. It is literally like watching grass grow, not to mention weeds and wildflowers. Yet it changed how one saw the High Line—and not only because Sternfeld had access, as the public then did not. By shooting down the tracks, as if waiting for a long departed train, he gives it length and breadth, and he rescues it from the dark, looming mass on the street below.

Of course, he shared that goal with advocates of development. Call it a triumph or a tourist trap, but it is hard to imagine the elevated park today without his efforts. Change, he seems to say, is slow but inevitable. It is inseparable from decay but by no means hopeless. It takes looking at familiar surroundings with a fresh eye. It also takes photography.

One can see all those thoughts emerging in "First Pictures." Not much is going on. Nothing much unites the show other than beer—a six-pack trailing at the waist, post-teens with cans held high, a weary jukebox in New Orleans, or men gathering in their private space in front of the TV. An Adonis, in his own eyes at least, catches some rays. Kids pose eagerly for the camera, holding up their modest triumphs from shopping. Today their grins would turn up an hour later on Facebook.

They could be anywhere. The beaches could belong to Florida or California rather than Nags Head in North Carolina, where Sternfeld passed a summer. The malls, like the kids with their drinks and their smiles, belong simply to suburbia. A gnarly face crosses beneath a street light, with a high-rise blurred in the distance, but one looks in vain for a street sign. One sees already a twin longing, for a sense of place and for something larger. One can see why Sternfeld was about to go in search of America.

They may also seem downright amateurish. In part, the photographer is finding his way. He is still working with a small camera, before switching to a larger format, and still experimenting with Kodachrome. If they seem garish (those nice bright colors), he is working out how a few strong hues can shape a picture. The gallery notes the Bauhaus practice of colors as building blocks. Compositions seem cut off arbitrarily—in contrast to set-ups, arty compositions, or deliberate disruptions. They make a nearby show of Bertien van Manen, with strikingly similar themes, look downright phony.

Or are people now more phony? Probably not, but it can sure seem that way. Mall rats looking up, as if for a UFO, come close to tourists by Duane Hanson, but without the sculptor's sentiment and cynicism. A girl takes her pose from Andrew Wyeth and Christina's World, as she relaxes in front of a parking lot at Sears. Sternfeld could be making fun of her or of fine art, but she hardly cares. Without Christina's quaint dress, pioneer slimness, and dark longings, she could be that much closer to the American dream.

Five Americas

Sternfeld conceived the work as four series—early explorations starting in 1971, the North Carolina beaches in 1975, New York and Chicago in 1976, and New Jersey malls in 1980. One might think of them as four Americas. Already he is thinking in terms of fixed assignments. That places him in a documentary tradition, just as the New York scenes go back to street photography by Helen Levitt. In the years ahead, he would turn to the Roman countryside, violence in America, a public cemetery, the folk architecture of Queens, and of course the High Line. First, however, comes a fifth America.

Maybe he had to tackle America, like Walker Evans or Robert Frank before him. Lee Friedlander has never gotten off the road. "American Prospects" came together at MoMA in 1984 and as a book in 1987, and it suggests how photography got from them to the staged weirdness and scale of Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson. One remembers beached whales, a car caught in a mud slide, or a boy perched on a car's hood, at once lost and defiant. One remembers the fireman at a pumpkin shack, itself lost in a field of green and orange, as a fire rages in the distance. One remembers a swimming pool, "Wet and Wild"—with bathers like lost souls, folded white umbrellas like ghosts, and a scarily winding platform above.

Unlike in "First Pictures," Sternfeld layers foreground, middle ground, and background—not unlike William Eggleston at Los Alamos. He also works with color, even as Eggleston's color at MoMA in 1976 or Joel Meyerowitz still came as something of a shock to art photography.  Above all, he opens the 1980s with irony and darkness, much like the "Pictures generation." He is still seeing ghosts at the cemetery or in the weeds above Chelsea. One can find hints of them in "First Pictures," like the cars lurching out of Seaside Cafeteria, but one has to look hard. Mostly he is still in transit in the 1970s, from humor to irony, from faces to narratives, and from an America identity to politicization.

Above all, he opens the 1980s with irony and darkness, much like the "Pictures generation." He is still seeing ghosts at the cemetery or in the weeds above Chelsea. One can find hints of them in "First Pictures," like the cars lurching out of Seaside Cafeteria, but one has to look hard. Mostly he is still in transit in the 1970s, from humor to irony, from faces to narratives, and from an America identity to politicization.

In each case, he stops short. The surfers and drinkers stop short of the confrontational lifestyles of Catherine Opie or Nan Goldin. Passers-by stop short of the urban freak show of Diane Arbus or Garry Winogrand. Police driving up to a man in shorts pointedly stop short of confrontation. A famously bland decade still had room for sex, AIDS, and punk rock, but leave those to people like Robert Mapplethorpe. The only strangeness here is the strangeness of the familiar.

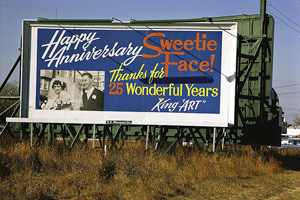

The familiar, for Sternfeld, is not so much unsettling as unsettled. He called the city series "Rush Hour," but commuters look more stranded than hurried. They also look at peace with the routine. A pregnant woman at the beach, trailed by a black dog, could condescend to them both, as if she too were inhuman, but instead feels all the more real. Even a child heaped in with the laundry or an ad for a chimp as house pet is downright endearing. In the very first series, "Happy Anniversary Sweetie Face," a billboard gives "thanks for twenty-five wonderful years," and I dare you to dwell on the sharp metal edges behind it.

Maybe Sternfeld had to start over with "American Prospects," once and for all, because the world had left those years behind. As Philip Larkin ended a poem, "Never such innocence again":

And the shut shops, the bleached

Established names on the sunblinds, . . .

And dark-clothed children at play . . .

The tin advertisements

. . . and the pubs

Wide open all day—

And the countryside not caring. . . .

Larkin was writing about England on the brink of World War I, and I have edited out the Anglicisms, but it leaves a pretty good description of "First Pictures"—give or take one thing. One is seeing not the loss of empire, but growing up.

Tabloid New York City

Try to remember when crime was raging but cops were heroes. Jill Freedman thinks she can. She followed them day after day and night after night, from drunks and psychos to dark streets and roach-infested hallways. She followed them from 1978 to 1981, almost to the year when Sternfeld was discovering "American Prospects," in two of Manhattan's toughest precincts and three of its toughest years. She dedicates her photos to them, unabashedly. In print, the titles expand into odes to a vanished New York, broken into lines like poetry.

They worked Midtown South, a no-man's-land between Penn Station and Time Square—the Garment District, the Port Authority and seamy hotels by day and by night. They worked the East Village, before the East Village art scene, when kids played with toy guns and pointed them at a squad car with impunity. They could not bring safety, but they could bring (to borrow from her titles) a Human Touch to the sleeping woman who may never have felt it again. They could not rescue lives, but they could restrain, if only for a moment, the child Always Running Away, and they could offer a grateful suspect a Free Lunch. They could not do much about crime, but they could battle Boredom at a parade, the sawhorse framing a face that looks more like George Harrison than a victim of poverty. They could not save a Suicide, but they could act as Partners, hurtling a wall together like superheroes.

Maybe it does recall one's favorite comic book, in which only a Jersey Driver can interrupt the Gotham City story. Two policemen part their uniforms to reveal Hell's Angels t-shirts, like secret identities. A man raging on his back on the street has the expression of the Joker. Light reflects off the silhouette of the one overt horror, the suicide, like off a masked villain, and the struggle is unending. The heroes and villains laugh together, even at a bank robbery. The man Stabbed Twice in the Guts, his eyes a drugged or otherworldly glow, will live to fight another day.

I remember, too, or so I like to think, quite apart from urban photography or disaster chic. I had returned to the city, after college and too many trips through the Port Authority. I knew the East Village, if only from too many early mornings fighting off the sounds in my head. I lived south of Midtown South, in an illegal loft above a topless bar, where I never once went in. It seemed a gentler, more affordable time, when I could amuse the homeless by running laps around Madison Square, to pretend cheers. I did not have to choose between high-rise condos and the Museum of Sex (because neither existed), I did not have to hurry through too many galleries to be fair to or to believe in art, and I did not have to call it Chelsea.

I wonder, though, just as I wonder about the gratitude and the laughter. I wonder about other memories than hers, of crime and of racial profiling continuing to this day. It took a later commissioner under Mayor Dinkins and then Mayor Giuliani to reverse the ideal of efficiency that kept police so often off the streets entirely, in their cars, and behind the blue wall of silence. For Diane Arbus, a smile could turn into a freak show and a camera could confront both heroes and villains, not to mention the viewer. Not for Freedman, born in 1939, who helped to create the heroes along with the smiles. Look again, and all parties are posing for the camera, even after a Bar Fight, 2 AM, Avenue C.

"Street Cops" shares the conventions of the tabloids, in composition as well as complicity. Freedman crops a scene to frame the central actors, and the city falls behind them as it may. She punches them up, too, as with a crime scene as Pietà. She allows them their innocence, a cigar in place of a pistol. Those visceral conventions, though, for all my objections, have their place in memory. After all these years of Pop Art, politics, and appropriation, welcome back to tabloid New York City.

Joel Sternfeld's "First Pictures" ran at Luhring Augustine through February 4, 2012, Bertien van Manen at Yancey Richardson through February 11. Jill Freedman ran at Higher Pictures through October 29, 2011.