6.20.25 — One Third the Earth

New York’s largest museum just got bigger, a lot bigger. The Michael C. Rockefeller wing has returned after a long and splendid renovation. Newly designed and opened to the public June 1, it brings to New York the very origins of civilization and the very idea of art—and I offer review and a tour for the test of this week.

It displays more than seventeen hundred objects from three continents and six thousand years—and that only a fraction of its founding contribution from Nelson A. Rockefeller, the former governor of New York and vice president of the United States. (It initially refused his gift.) With art of Africa, Oceania, and the ancient Americas, it now represents over a third more of planet earth. Maybe you never knew it existed, even before it closed in 2001. Even if you were old enough, fewer approach the wing for modern and contemporary art from Greco-Roman antiquities on the first floor, rather than Impressionism in France a floor above. Now, though, the invitation is hard to refuse.

It displays more than seventeen hundred objects from three continents and six thousand years—and that only a fraction of its founding contribution from Nelson A. Rockefeller, the former governor of New York and vice president of the United States. (It initially refused his gift.) With art of Africa, Oceania, and the ancient Americas, it now represents over a third more of planet earth. Maybe you never knew it existed, even before it closed in 2001. Even if you were old enough, fewer approach the wing for modern and contemporary art from Greco-Roman antiquities on the first floor, rather than Impressionism in France a floor above. Now, though, the invitation is hard to refuse.

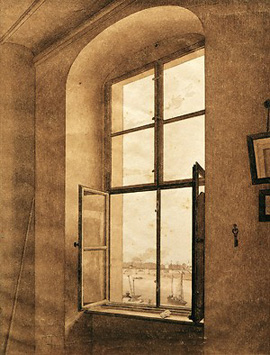

Is Africa the dark continent? Here all three continents are swimming in light. After the ordinary grid of modest rooms with perhaps an atrium for other wings, like a sales destination or a maze, this wing has tall ceilings that ease the flow from one room and one continent to the next. Broad entrances from room to room, some with arched tops, ease the transitions. The entire south wall is tilted glass, creating vistas and pulling in the light. Glass partitions with short white stripes help to define divisions while visually eradicating them.

Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture, working with Beyer Blinder Belle and the Met’s design department, enable all sorts of transitions. You may run up against the glass, but you can always start afresh. To mix things up further, the arts of Oceania resume to the south after a break for the Americas. And that raises another tough question: what are these continents doing together? Is this simply the Third World, stuck in a Cold War past? Is it more than a wealthy donor’s tribute to his son Michael, likely lost at sea or killed on an expedition to New Guinea?

Then, too, is the matter of time. A wall of contemporary African photos by Samuel Fosse faces the modern wing directly. Fosse packs his portraits with no end of dignity, whether in dress uniform or bearing the numbers of a criminal. The curators integrate other recent work throughout—including El Anatsui, known for his “metal tapestries” of colorful liquor bottlecaps and sheer scrap. They dip back to the nineteenth century now and then as well. If you had any doubt of the ancient world’s influence on the present, you can check them at the door.

The architects set a small gallery aside for temporary exhibitions as well. “Between Latitude and Longitude” brings Iba N Diaye of Senegal together with the European painting that influenced him, through next May 31. He admired equally the fraught expressionism of Francis Bacon or Francisco de Goya and the classicism and introspection of Rembrandt. In his own paintings, fields of color pour into one another—applying Abstract Expressionism to African sandstorms and African politics. But would he have agreed with the Met’s selection? He died in 2008.

Back in 1996 the Guggenheim Museum presented “The Art of Africa” as the dark underside of Europe, a place of primitive discord. The Met puts that and indeed its own past practices to shame. A video shows an ancient wall painting—in southern Africa and not in the caves of Spain. Actual objects pick up the story on the Nile, just as a show at the Met of African American artists placed them in context of Egypt and Sudan. If you are left with questions, be grateful for them. I know something about non-Western art and the world that spawned it, but nothing like this.

All I can do is to share the bare facts and my own very personal impressions. You are left to the curators and on your own. The Met, though, has some hints to get you started. If, like me, you are nothing short of overwhelmed, the cultures here took that as a necessary function of art. And they felt an imperative to provide continuity over the centuries—to bring ancestors and dependents fully into the present. The very first human, they say, was an accomplished carver, and I believe them, and I continue next time with the hall’s unifying features and the art of Oceania.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.