Attitude Adjustment

John Haberin New York City

The 1993 Whitney Biennial

Some of my favorite critics argue that art must struggle fiercely against the past. For them, tradition is a politically charged burden, and the only plausible reply is a politically aware one. Art too, then, requires a radical discontinuity, in every sense of the word radical. Its confrontation with the past promises freedom and a dizzying loss.

A sprawling exhibition of contemporary art, the 1993 Whitney Biennial, agrees. Yet more remarkably, it helps to convey the emotional experience of that loss.

Realism and despair at the Whitney

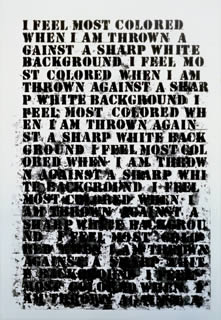

What many visitors found at the Whitney was the anger of New York City in 1993. The reviewers whose job it is to defend art saw only strident dogma masquerading as critique. What struck me instead was a pervasive sense of despair. It might be the cry of a woman's body reduced to a slab of fat and a lump of chocolate. It might be real-life beatings and affronts to a black person's dignity literally put on a pedestal or made into a totem.

Marx and more than a few anthropologists have commented on a progressive erosion of a private realm apart from the political. Some important critics of modernity, beginning well before Michel Foucault, have described this change as an annihilation of the individual. Ironically, artists now seemed compelled to enact that demolition as it would appear to an individual consciousness, by shouting ever-more loudly, like someone drowning and crying out for help.

Amid those screams, individual voices sounded overly earnest—even voices as clear and challenging as that of Cindy Sherman. Sherman's photographs blur the lines between artist as a fantasizer and woman as the fantasized. They tie art as reenactment to sex as a ritual, a chilling show put on for the benefit of others. Here they seemed, unfairly and perhaps unnecessarily, like an unhappy child thrusting its dirt in the face of its victimizer.

It was not precisely art brought down to the supposed level of politics. It was politics reduced—and I mean driven, not exactly trivialized—to theater, and a rather well-publicized repertoire company at that. Videos trapped visitors far too long in overcrowded rooms. At least one installation had me wait outside for half an hour, quizzically inspecting others around me, only to see a fragmented projection in a darkened room of much the same people. Past and future Biennials have behaved like amateur circuses—which is part of why I go. This one recalled Disneyland, with its long lines to view staged, larger than life reproductions of everyday banalities.

Often that meant an artist's misjudging the audience. Take Glenn Ligon in his Notes on the Margin of the Black Book, a long corner of photos by Robert Mapplethorpe broken by typed quotations. Did Mapplethorpe's modernist sensibility foresee shocked reactions to his elegant eroticism? Ligon meant to let me decide. He raises issues, new and old, about art institutions and gays, from attacks on arts funding to the exclusion of blacks from behind the camera.

At the Whitney viewers pretty much had to take sides, often without knowing it. Probably most people (presuming that few of Jesse Helms's fans attend) hardly noticed Ligon. They saw Mapplethorpe reducing blacks and gays to objects of desire. Probably most of the rest admired this Ligon fellow for his lovely photographs. Once a reductive strategy is raised (even in opposition to the status quo), there is no telling where it will lead. How did Warhol's silk screens lead to Warhol's Factory?

Distrust as theater

Some of the awkwardness of the 1993 Biennial could be explained by the curators' plans. They intended to open the museum exclusively to outsiders, or at least only to first-time beneficiaries of Whitney hype. Often an installation that works in alternative spaces like P.S. 1, with short bursts of attention from a nonpaying public, conveys obsessive control over a museum crowd.

Some of the best and worst of the exhibition, however, also reflects particular distrust of art as an institution, especially art in America (as the same curator, Elisabeth Sussman, is to discover again in the less directly politicized 2012 Whitney Biennial). Suspicion explains the explanatory labels so often used here: they keep an artist's meaning from being changed, as it were, without written permission. These artists felt a need to create their own theaters, now that existing ones serve mainly to channel private funding and certify personal acquisitions.

No wonder the many curtained rooms, outsized displays, violent images, and deliberately "unesthetic" subject matter reminded me of another instance of art as grand theater: I thought of Frederic Edwin Church, with his nineteenth-century exhibitions of large-scale paintings. He put a landscape on display in darkened room amid actual plants. In this theater the artist gets to pull the curtain strings.

The difficulty of modern art was supposed to demand careful, slow responses. This art was difficult in the sense of a standardized exam, one the public should be obliged to pass.

Artists at the Whitney were all forced into an uncomfortable position with respect to the self, art institutions, and art history. The rituals they enacted simultaneously deplore and sanctify an inner life. They decried the museum while brandishing it like a weapon. They called for a less formal, more socially committed art while generally avoiding references to any past older than the headlines of the Los Angeles Times.

The more they understood the past, the less they could make use of it. Rosalind E. Krauss, the well-known critic, has tried to deflate the "originality of the avant-garde." In their own stand against it, these artists demand a sharper break from established practices than any generation since before Modernism.

Harold Rosenberg, the great defender of Abstract Expressionism, compared Pop Art to the academicians of the Baroque. He might have spoken more aptly about the abstract painters left out of this Biennial. I think of their critical respect for tradition, fullness of ambition, and vast command of their media as well as their flaws. If so, the Whitney's new realists might well evoke the ideological battles of the late nineteenth century, when the whole myth of art as an individual's rebellion is supposed to have formed.

Irony and attitude

The Biennial reflects dilemmas beyond just the arts. Outside white male America, the past surely must look simply frightening. Within it, all the old myths are increasingly unavailing. Yet dreams of a safer private realm did not suddenly vanish from "real life," of course, any more than from the Whitney's comfortable surroundings at 75th Street and Madison Avenue.

To the contrary, everyone agrees, America wallows in them on a scale unknown since at least the 1950s. Like men with leather jackets back then, I do my best to assert a comfortable level of rebellion. Say, I loosen my tie and roll up the sleeves of a button-down shirt at work. Perhaps the equivalent for a woman amounts to getting on the stair climber with short hair and fashion accessories.

The strangeness of it all came to me again weeks later, as I sat two blocks down from the Whitney. There, in a terribly wealthy church under the hot glow of arc lights (the better to permit photographs), I attended my younger brother's graduation from private school. The lone, sketchy reference to AIDS aside, it was striking for its lack of political statements. One heard dull talk of beginnings and endings, memories and self-discoveries—all very sincerely expressed. And all of it was spoken with the knowing gestures and snide tones of someone who would not be caught dead believing a word of it.

When my brother's fellow students indulged in piety, their delivery did not imply irony and reflection. Rather, it was a fail-safe way to preserve a student's dignity, the coherent narrative of an individual future, and the prestige of the social leaders giving the speeches. Outside of private school, students behave more dangerously, at least in the short term. Their strategies, however, are directed toward much the same ends.

Sanctimony and rebellion are behind the Whitney's overdramatized rituals. That is why they often seemed at once so nasty, so necessary, so appropriate, and so inadequate. For 1993, it was at last a Biennial with attitude.

This Biennial ran in the spring of 1993, at the Whitney Museum of American Art. You might wish to look ahead to the 1997 Biennial, 2000 Biennial, 2002 Biennial, 2004 Biennial, 2006 Biennial, 2008 Biennial, 2010 Biennial, 2012 Biennial, 2014 Biennial, 2017 Whitney Biennial, 2019 Biennial, 2022 Biennial, and 2024 Biennial.