Fair and Balanced

John Haberin New York City

The 2004 Whitney Biennial

One could get lost at this Biennial. Perhaps one should, if only to appreciate the rootless art scene it portrays so well.

Everything you heard is true

A colorful preview, in the Sunday Times, promised a Biennial of discoveries. These young artists were going to catch the art world by surprise.

The writer could show their pictures, every artist with a different ethnic heritage. But not even The New York Times—no, not even the Whitney—could know much more until the opening. I thought of Michelangelo alone on his scaffolding, behind the closed doors of the Sistine Chapel. The exhibition catalog, necessarily prepared in advance, gives one page to each artist, but rarely a word to the art.

After the opening, reviews told a different story. The Whitney, for once, plays it safe. Remember, not all that long ago, when shock art was in vogue? For that matter, remember when shock art shocked?

With three curators, all from the museum itself, the 2004 Biennial brings neither a thesis nor a blow against the empire. After barnstorming the country two years ago, the Whitney, most reviewers agreed, comes home. Responding to criticism, it tries to please all its constituencies, including the best-known galleries. The Biennial may not leave a lasting impression, but what does these days? Maybe it offers a place for the Whitney—and for art—to begin.

Which version has it right? Surprise: it is all true. This Biennial promises to have it all. Even the hanging refuses to take sides. Using words too corporate for me to quote, the entry wall promises not themes but overlapping projects.

Can you please everyone? That premise, with its echo of marketing, sounds about right for art today. I had a great time, and I learned a great deal. The artists truly do come from every possible background and, often poignantly, seem cut off from their roots. If one ever felt adrift in art these days, once inside one feels much the same way. So start by following the plan: get lost.

All over the place

The Biennial snakes in and around the museum's five lowest floors, taking more advantage of those mobile walls than any exhibition I recall. It opens onto alcoves one never expected, for video and installations. It stops short only of entering the bathrooms along with "Greater New York" at P.S. 1.

It dares one to catch so much as a glimpse of sculpture on the roof and scattered the full length of Central Park. It challenges one to find a way in. The lower courtyard holds a metal chamber, like an oversized beer keg. I never found a way to enter, much less a drink.

It leaves one alone, in a small, dark room. One stands on a narrow walkway, suspended between the multiple reflections of mirrors above, electric lights seemingly everywhere, and a pool of water below. And then, in a matter of seconds, the guard opens the door and tells one to move on. There is a line, after all.

If that walkway, by Yayoi Kusama, suggests the shape of the Chelsea piers, the crowds filing into Chelsea galleries, and the glitter of downtown, it should. The 2004 Biennial wishes desperately to represent the art world. If it were any more fair and balanced, Fox would sue.

On the one hand, curators bend over backward to include mainstream dealers. The wall labels could pass for a gallery guide of West 24th and 26th Streets. On the other hand, the show may include more young artists than ever. It certainly integrates multimedia more successfully.

It does not stray much from New York and Los Angeles, but it features a solid number of women, people of color, and even national origins. Artists come from Europe, Asia, and Africa, and several really made their careers in England or Germany. Isaac Julien may count as American art. His videos trace their roots to European painting, Caribbean music and early rock, and the black ghettos of Baltimore. He lives, however, in his birthplace, London. Yusama, no stranger to New York, lives in Tokyo.

Art's generation gap

For once, the older, white males look like the students. It may even excuse their bizarre selection.

I think of David Hockney as still famous more for his odd opinions about the Old Masters than for his art. Here he could pass for a West Coast protégé of Elizabeth Peyton, whose offhand portraits cover the wall preceding his. I remember Stan Brakhage, the pioneering filmmaker, as a dispassionate recorder of nothing. When he shares a video room with Julie Murray, however, the swirling colors and objects of perception look sensual and contemporary. I dare anyone to know within fifteen seconds whether his or her work is playing.

Robert Mangold may not leap to mind first among formalist painters. His curved lines, shallow pictorial space, and practiced departure from symmetry fit just fine, however, near Alex Hay's illusions of wood veneer and Kim Fisher's decorative abstractions. Mel Bockner's word paintings, with bright colors and bitter negatives, look less like lessons in the philosophy of art and more like street talk.

Conversely, the Biennial has a decided nostalgia for the 1960s and early 1970s. Even the catalog reprints literary icons, such as Jorge Luis Borges and Anais Nin. It suggests a generation defined by a revolution its parents could not sustain. And that revolution means not Modernism but politics and pop culture. It means not Minimalism but excess.

Some artists, in true Goth fashion suitable to the dark, private visions in many galleries, replay the past at top volume. Liz Craft's sculpture turns images of death into heavy metal. Dave Muller covers an entrance wall with an elaborate family tree of rock, which then replays backwards—in mirror reflection. Esthetics must have given out with Grand Funk Railroad. A collective called avaf (for assume vivid astro focus) turns a room into a party appropriate to the other kind of Chelsea days. You know, the kind with colors other than black.

In politics, too, art looks back. Sam Durant starts with grainy reproductions of antiwar demonstrations. Then he mounts the slogans as light boxes in the museum lobby. Gestures like these soften political rebellion, in more ways than one. Mary Kelly, known for a far harder line, recreates in lint an image from the 1968 Paris streets. In context, the anti-Bush scrawls from Raymond Pettibon seem downright strident.

Rootlessness and respect

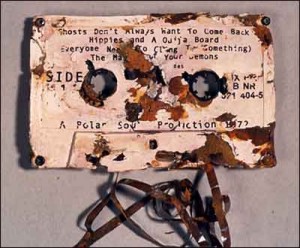

Respect for a past just out of reach appears in subtler ways as well. It appears in Dario Robieto's fine, weathered objects. It appears in Harrell Fletcher's video of a nursing home, with residents barely able to suppress a smile while spouting a mix of institutional clichés and James Joyce. It appears in the ability of Laura Owens to spin painting into unsettling myths.

It appears too in the frequent images from nature, often clearly despoiled, like a longing for a purer, safer Earth. As with Fisher or appealing work by Cameron Martin and Julie Mehretu, such imagery enters whenever painting veers too close to abstraction. Sharon Lockhart shoots couples hopelessly raking hay, Amy Cutler sketches a campground all but waiting for a summer movie stalker, and Katy Brannan's photos look equally ill at ease, while videos from Jack Goldstein and Peter Hutton alike depicts patterns of soft light rippling across water. Even Robert Longo, once a postmodernist of "The Pictures Generation" with an eye for yuppies at play, is painting waves. Longo calls his concurrent show in Chelsea "The Sickness of Reason." Earth Mother worried that he never calls.

If all this sounds glib, often it is. It may unite two generations, but it makes the moments of pomo outrage in the middle look toothless. Molded gray blobs by Richard Prince could pass for automobile hoods melting in the heat. If he means another example of macho culture, he has me fooled. When younger artists such as Laylah Ali and Olav Westphalen represent cultural conflict in a language colored by alternative comics, they risk turning politics and identity into a cartoon.

At the Whitney, as increasingly for Julie Mehretu, consciousness of the past translates into conflict in the present. That helps explain, too, what the Biennial chooses to leave out.

It cannot get too personal or too theoretical, so forget strictly conceptual art. It cannot get too impersonal, so forget video that cannot play out in linear time. It cannot get too dogmatic, so forget abstraction for its own sake. It cannot get too real, so forget representation of actual urban or suburban America. It makes at best a token bow to photography, although Catherine Opie, Lockhart, and Grannan make good choices. Roni Horn's image, a young man repeated as tiresomely as any ad, sure looks like a pop star, but actual brand names are verboten.

Like the choice of artists, these works admit a range of voices, and they allow people of varied backgrounds to speak as individuals rather than as symbols. Is that enough to redeem the creature comforts of the exhibition as a whole? At the Studio Museum in Harlem, Eric Wesley led off a show that treated blackness "Freestyle," a predecessor to later shows called "Frequency," "Flow," and "Fore." He fits naturally here, with a huge contraption that has little to do with race or, for that matter, much else.

Softening the edges

Where the Biennial takes flight, it is because distance from home translates into a felt sense of loss. It is because the softening of boundaries can make the personal political.

A softer edge draws one closer to Cecily Brown with her battered surfaces and equally battered subjects. Do Brown's women, as if in perfect response to the battered male outlines of Jean-Michel Basquiat, look almost beautiful now? It humanizes them that much more. Does their naked flesh looks less literal? It places the burden on the viewer to feel their nudity as a construct of desire. Pairing Brown with Chloe Piene's scraggly women and bared crotches, the Whitney introduced me to a good artist and brought out at once the dark and playful sides of both.

Sue de Beer, too, has a softer edge, as in her video recollections of early America, from the plush, stuffed animals that turn the floor into a communal sofa to the quiet voices on video. Even the title, Hans und Grete, sounds comforting like a fairy tale. The environment draws one in, and it makes one deal frankly with her tales of transgression. And Eve Sussman's multiple perspectives insert illicit romance even into Old Master painting.

A softening of boundaries lets Emily Jacir treat conflict in terms of subjects rather than simply victims. She asks Palestinians what they would most want to recover if they could pay one visit to their homeland. Their stories come down not to questions of rights and possessions, but to memories of family and of love. She documents the responses in photos and in text, in more than one language. She also includes people with American and Israeli passports. They cross boundaries because of what they have lost, but not only in their imagination.

Behind a curtain, in the adjacent room, Marina Abramovic represents estrangement more darkly but without explicit violence. A mass of people form a five-pointed star around the head and four limbs of a body stretched out on the ground. Then they leave him exposed and assemble again, in an unending ritual of community and death. A skeleton leads a black choir. Women in traditional scarves stare and drone eerily, and I could not guess the language. They and Abramovic could well be articulating the dark conflict that Jacir dreams at an end.

One can see in these works a more highly charged exchange between generations. One can see that conflicts and compromises are not going anywhere fast. One can see the price art pays for failure or success.

Having it all

More often, the exhibition goes down a little too easily, even compared to contemporary art at MoMA. I left wondering if art has come free of consequences for the past, present, or future. Perhaps it has, making this Biennial even truer to the present than the curators dreamed. One has many reasons to look forward to a Biennial. This time, as with so much of the art world, one can have it all.

People go to a Biennial to complain—about who gets in, who gets left out, and who gets to decide. They go to find the next center of the art world. They go simply to learn about and to enjoy the art. And they go for a nice afternoon in a nice part of town. In short, they go for the curators behind it all, the hot galleries on display, the artists, and Central Park just up the block.

Past Biennials tended to privilege one or the other, very much as part of their time, in what one critic has called art's battle for Babylon. The 1993 Biennial had a strong point of view, befitting the vitality of critical theory. Soon, however, with irony and Soho alike officially dead, people were worrying again about galleries and the art market. In 2000, with the art market intensifying, things naturally shifted to hot artists. Finally, facing globalization and financial meltdown, the 2002 Biennial tried to forget the whole thing—and I can add with hindsight that the 2006 Biennial and 2010 Biennial will leave America even more decisively, while the 2014 Biennial will look to the past. Drawing on the blandness of art schools nationwide, plus the first outdoor installations, it offered the first biennial for spring in Central Park.

This year, the curators are again looking for signs of tradition and renewal. And they find signs of hope here in New York, as the center of a nexus of people, places, and change. It makes sense, amid Chelsea's continued boom and the global procession of Armory Shows and art fairs. It makes sense, too, as artists and dealers escape to Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Long Island City. Most of all, it makes sense when, for now, art appears to have given up on setting an agenda.

This Biennial really does have it all. It has clear curating, in the careful arrangement of galleries and media, as well as in the loose thematic arrangement—from painterly objects on the fourth floor, through more political themes on the third, down to sheer collapse in the lobby. It has the big dealers, and it has plenty of artists I wish I knew better. It even takes over more of Central Park than last time.

Is pleasure enough? Can it live up to the true grit of those artists who escape to working in Brooklyn? Who will sustain a revolution today? I should give the show credit enough for forcing me to ask.

A postscript: the great outdoors

A few weeks after completing the review just now on the packed, winding interior, I sought out its more loosely scattered parts in New York City's finest landmark. (The 2008 Whitney Biennial will spill over, too, but to the Park Avenue Armory.) If the Biennial aims to please, its extension into Central Park carried that message to outlandish proportions. One could call it the Children's Biennial. In fact, one piece, mounted for a weekend only, sat barely a hundred yards from the actual Children's Zoo, at the Arsenal that normally houses park administration.

Dave Muller's Three-Day Weekend had some more or less random wall paintings, as well as vitrines filled with nothing in particular. Their label, "The Wrong Gallery," was on to something. The centerpiece, however, was definitely for children of all ages, a thick air mattress. During my visit, a little girl was jumping happily, but the treat for me was in penetrating the lovely old building.

The park must have timed it all for New York's unofficial early start to summer, the opening of the Sheep Meadow. The avef collective, which within the museum looks nostalgically to the 1960s, gave the pavement beneath the nearby roller-bladers the look of Peter Max on speed. Definitely easy to swallow or, just as well, ignore.

Another opening planned for the same weekend, a takeover by Yayoi Kusama of the pond at East 72nd Street, was officially deferred until May. By the Biennial's close, however, I never learned if it had even taken place. However, the rest of the great outdoors continued its run. Liz Craft may have forgotten that most of the park's southeast plaza already looks like trash, but others stuck strictly to kid stuff.

Olav Westphalen introduced the zoo with a rather unthreatening tiger, while David Altmejd took an overlooked hill and his usual creepy scale, by the East Drive just north of the 103rd Street transverse, for self-proclaimed werewolf heads. (Who am I to question them—and who would answer?) The label described a tension between the desirable and the repulsive. I am guessing that the tacky, encrusted, gemlike crystals supply the first, the decaying animals the second, but when it comes to Altmejd your guess—or your pet werewolf's—is as good as mine.

Paul McCarthy's ode to Michael Jackson looked more like Mister Potatohead, and the museum did well to describe his pink inflatable doll some three miles north as "goofy and awful." Yet another McCarthy balloon rested, inconspicuous and inaccessible, on the museum's own roof. The nicest part of all? Unlike in London, where his sculpture sat in front of the Tate, here I could never get close enough to puncture them (entirely by accident, you understand) with a sharp pin. I guess that leaves only words as a grown-up child's weapons.

The 2004 Whitney Biennial ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through May 30, 2004. Some of the outdoor work is visible only in April. Robert Longo's show at Metro Pictures, actually paintings of mushroom clouds, ran though March 27. Other reviews look ahead to the 2006 Biennial, 2008 Biennial, 2010 Biennial, 2012 Biennial, 2014 Biennial, 2017 Biennial, 2019 Biennial, 2022 Biennial, and 2024 Biennial—or back to the 1993 Biennial, 1997 Biennial, 2000 Biennial, and 2002 Biennial.