A Dying Art?

John Haberin New York City

The Feverish Library and Charles Ritchie

Are books dying, and if so, what will be lost? What if such common objects vanished from their shelves? Does it matter that books demand not just to be seen and touched, but to be reread?

A show on the theme of "The Feverish Library" sees a book as a chance to get conceptual, while an annual group show at the Center for Book Arts sticks to creature comforts—starting with its title, "With Food in Mind." Charles Ritchie sees it as a chance to get personal. When you see a house for the first time from across the road, shrouded in trees and the night, you become a stranger. Ritchie would like to invite you in. He would even like to share what he calls his "Drawings and Journals." Yet they rely on much more than nostalgia, even when it comes to the handmade.

Books as object lessons

Were books to vanish, something solid will have gone, as plain and iconic as Minimalism. So will the ability to share it, along with something of oneself. So what if the sharers are also imposing their message on others? A book is, after all, a burden or a boast, a chance to be human or a chance to be clever. It is a chance to make art as well and also, just maybe, to avoid the temptation to see even a fine object as a single, unchanging thing. It is also a chance to make information portable, to learn, to revisit old words, to alter old meanings, and in short simply to read.

Of course, if books disappear, libraries will have gone, as places of innocence and awakening—or as social centers, while students pretend to study for the finals. Other sexual awakenings lie between the pages, sometimes disguised as art. Books catalog art and museums, in between serving as optical experiments, and those, too, may not make the transition to digital. Living room shelves will have gone, whether as portraits of their owners, as upscale furniture, as sites to gather dust, as miniature natural histories, or as a household mess. Out, too, will go those already obsolete obsessions in encyclopedias and Who's Who, both as much bywords as Renaissance bindings and actual books. Oh, and did I mention the chance to snicker at cheap novels and the people who read them?

Matthew Higgs puts names on all these, but not the names of authors. "The Feverish Library," is less feverish than encyclopedic and knowing—and the knowing glances come from artists. For his own contribution, patterned after Joseph Kosuth, Higgs asks gallery artists for their favorite books, and apparently they have learned how to manage their image since Kosuth's time. Choices include The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint (where cognition may not include getting the trade name right), along with James Joyce and The Wind in the Willows. Books may be dying, but irony in art is maybe a little too alive, from a curator who just this summer took "Furniture" as a theme. Indeed, I could simply name names and let you draw the obvious connections, but here are a few hints.

Of course, the girl in the library is Cindy Sherman, from Untitled Film Stills, while Candida Höfer's photo identifies a library with all those awful oppressive institutions of Western civilization. Jorge Pardo spots a portrait (of someone who really does appreciate Joyce), Wade Guyton a display case, Josh Smith an obscured encyclopedia, Clegg and Guttman (but not, alas, Mickey Smith) a Who's Who, Carol Bove a natural history, Matthew Brannon and Martin Kippenberger the overblown furniture, and Moyra Davey a mess. While Mark Dion imagines an educational opportunity, in a mobile library, John Baldessari teaches a plant the alphabet, in the same singsong as in all his lessons on the Southern California intellect. For those who still cherish the object, John Latham supplies the cloth binding and the economics lesson, Richard Artschwager the Minimalism, Tauba Auerbach the optics, John Stezaker and Steven Baldi the art, Stezaker and Anne Collier the desire, and Rachel Whiteread the dust. David Hammons knows the Bible as a dark presence in the African American community. Richard Prince ogles and snickers, and that will be that.

Only Guy de Cointet claims to speak in his own voice, with A Page from My Intimate Journal, but elsewhere Jen Mazza can hardly stop herself. She paints pages and book covers as exuberantly as Elaine Lustig Cohen, cherishing the illusion and the flatness. Still, it is first and foremost a display of taste—for a time when, as it happens, flatness and illusion mattered. She goes back to Modernism, but in the meditative intimacy of Clive Proust and Clive Bell rather than the bravura of Joyce in Nighttown. She quotes Lee Lozano, who "can't be interested in form for form's sake." She remembers the postwar anxiety of Jean-Paul Sartre (in French) and Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Something gets left out, in all this fine irony and felt sincerity. I doubt that books are going anywhere, when they are portable, shareable, durable, and low in up-front expenses. And when brick and mortar stores for them go, New Yorkers may miss most the public toilets. Writers, though, will have less chance to find readers, and readers will miss out on discovering many a writerly voice or political idea, beyond the influence of tastemakers, echo chambers, and robot suggestions. Artists, it seems, see in books mostly public and private possessions, not encounters and evolution. Come to think of it, the latter view might make for more challenging and comforting art objects as well.

Comfort food

Art and books for me have a lot in common. Both keep surprising me and teaching me, and both are a kind of comfort food through a long winter. Art should challenge, but it can give pleasure, too. Maybe that is why the Center for Book Arts had a display the summer before, organized by Nicole Caruth, called "With Food in Mind." Nostalgia is all well and good, as is eating in. Its library could stand, however, a little more fever.

Of course, art is about more than comfort, perhaps especially when it comes to food. Leonardo's Last Supper captures a disturbing moment—or, if one trusts the late Leo Steinberg, an eternity. Another feast got Paolo Veronese hauled before the Inquisition, and the pioneering independent still life, by Caravaggio in the 1590s, threatens to land in one's face as a dangerous temptation. Between that and the turn away from realism, no wonder cake for Wayne Thiebaud in Thiebaud drawings is both so lush and so chilly, like a pun on the word icing. In still life, Dik Liu cannot help throwing in fast-food wrappers, the kind of thing that has blossomed into installations as trash heaps by Saraz Sze, Lisa Hoke, or Stephen G. Rhodes. Sometimes it seems as if the only comfort food left comes from Rirkrit Tiravanija, and he has served his curries in the gallery more often than most singles dine on leftovers.

Sure enough, Tiravanija turns up at CBA, but this time with the Soccer Halftime Cookbook. For actual servings, one could attend the opening, when Atom Cianfarani's Consume Love had to compete with the obligatory white wine. Her title sounds like comfort food, but the performance, involving the viewer in discussion, felt more like remedial education. More often here, creature comforts are inseparable from memories. They underlie the Victorian styling of Barbara Henry's prints, Emily Martin's paper pie plate, and Robert The's slice of chocolate cake—sculpted, he swears, from Reader's Digest. Heather Hart asks others to write their own remembered recipes.

Sure enough, Tiravanija turns up at CBA, but this time with the Soccer Halftime Cookbook. For actual servings, one could attend the opening, when Atom Cianfarani's Consume Love had to compete with the obligatory white wine. Her title sounds like comfort food, but the performance, involving the viewer in discussion, felt more like remedial education. More often here, creature comforts are inseparable from memories. They underlie the Victorian styling of Barbara Henry's prints, Emily Martin's paper pie plate, and Robert The's slice of chocolate cake—sculpted, he swears, from Reader's Digest. Heather Hart asks others to write their own remembered recipes.

For others, food connects painfully to the body in art. Eidia's Starving Artist's Cookbook alternates recipes with photos of Hannah Wilke and others in performance. Scott McCarney finds a photo of Leo Castelli smiling while standing over a stove with a teakettle. Who knew that dealers could be so ingratiating? For those still obsessed with what happens to food between consumption and Chris Ofili, Hugh Pocock throws in some poop, while Joy Garnett tweets from her own studio. Others may not be starving artists, but they are still, Isabelle Lumpkin insists, Starving in a Sea of Objects.

Still more often, starvation and consumption alike have political meaning. K. Yoland's Distracted Cook's Handbook includes directions for a "Libyan fry-up," while Jon Rubin and Dawn Weleski describe the Mideast as a Conflict Kitchen, much as for Stephen Shore. Susan Roma's fortune cookies predict social history, and Stefani Bardin and Brooke Singer diagram food at the nexus of global capitalism. Lost your appetite? One can always learn from Aleksandra Mir's How Not to Cookbook. For starters, "Do not experiment on guests."

A show like this could be a lot more experimental. On the other hand, "A Feverish Library" could be less conceptual and, if so, less predictable. The reopening of the Drawing Center, with artists who call their work diaries and notebooks, suggest some possibilities beyond nostalgia, and so does Charles Ritchie. Compared to most diaries, his "drawings and journals" seem less spontaneous. For all their script, they also seem less about his thoughts from day to day. But you never know, and the ability to look again, to reread, or to reinterpret is very much part of art and books.

Inviting you in

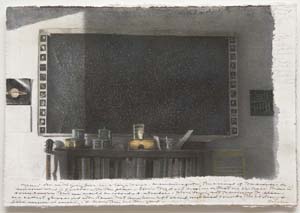

Works on paper often invite one in, especially drawing as meticulous as Ritchie's. You want to see what is on the artist's mind, and you want to see how it is done. Ritchie's work depends on its scale and care. Some of it functions as an artist's book, a particular interest of the gallery's, as well as a sketchbook or even a diary. Writing overlays an entire sheet, like a secret code. Probably only the artist can read his tiny script, but it is hard not to try.

The script is also part of a sheet's texture, along with the softness of graphite, charcoal, conte crayon, or the paper itself. It is Fabriano paper, the thick Italian kind, and the drawing brings out its surface. The paper often peeks through as well, and he says that he prefers to rely on it for whites—to invite one that much closer, through the illusion to the object. I cannot vouch for that, and watercolor clearly adds some of the brightest highlights along with spots of color. As so often when paper stands for white, it is hard to know. As so often, too, whites then have a greater intensity, well beyond one's association with a blank sheet.

Texture also adds detail, as of leaves. Ritchie says that "light is my essential subject," but light contributes less to tonality than to things—and shadows less to depth than to gradations. He names one drawing simply Graphite Night. In time, one does find oneself indoors, where the very objects speak of intimacy, like plants in the window, candles on a dresser, or photos on the mantel. Books on a shelf evoke the drawings themselves. The insistent artificial lighting places that much more emphasis on home, but do not settle in too soon.

Facing clapboard and private property, with no one at all visible inside, one has to feel at least a little excluded. Maybe the artist does, too. He depicts his home in Maryland, but he could be anywhere and nowhere. One cannot make out the photos he so cherishes or the titles on the shelves. His dense script is all but illegible. I wonder if he can read it the next day.

Inclusiveness in America does not come easily, even close to home. Think of Robert Adams a quarter century ago, walking his own neighborhood by night. Think of the perpetual encroachment of communities on nature—or the perpetual efforts of architects to reshape them both. Ritchie, born in 1954, may find that old-fashioned art comes with its own anxieties for the future. What if books are dying after all? The very density of his surfaces are a visual obstacle to entering, although also a welcoming.

Look again, and it gets harder to know obstacle from welcome, outside from in. Many images depend on reflections and refractions from the windows. You may have been inside with the artist all along, looking out. The sky is mostly dark, and the only stars are in a large star chart on the wall. The side of the house never quite parallels the picture plane, softening the depth and sense of a barrier, without removing either of them entirely. There is always a limit on how close one's gaze can come, which leaves nothing to do but approach in person and come in.

"The Feverish Library" ran at Friedrich Petzel through October 20, 2012, Jen Mazza at Stephan Stoyanov through October 14, and Charles Ritchie at BravinLee Programs through November 21. "With Food in Mind" ran at the Center for Book Arts through June 25, 2011.