An Everyday Minimalism

John Haberin New York City

Everyday Abstract – Abstract Everyday

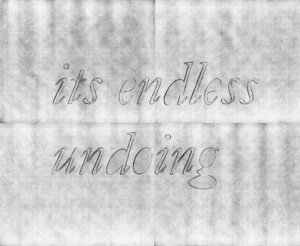

Furniture and Its Endless Undoing

I had been noticing something—almost enough, in this overblown madness of an art world, to call it a trend. It is okay to turn back to geometry and mass production, but not with the idealism of the Bauhaus or the rigor of Minimalism.

It is okay to rely again on collage, but not with an exhilarating disconnect, like the stuffed goat from a young Robert Rauschenberg, and not with the leaden irony of Damien Hirst or the "Pictures generation." It is okay to create what looks for the life of things like abstract painting, but not simply in paint and not simply abstract. In fact, it is okay to celebrate the origins of Minimalism, but as part of "light and landscape." It is okay for artists today to discover a Neo-Minimalism.

Call it an outpouring and a diversity, or, sure, call it a trend. I give shall even give it a name, that name, for the art of a subversive everyday. I have kept coming back to it again and again over the last few years, but summer is always a time to look back. As gallery group shows start pouring in, and they do, their very job is to look back. This year, they include superb shows of abstraction and vision. Three summer group shows, however, single out three ways of messing around with everyday objects—with "Everyday Abstract – Abstract Everyday" for the spare side, "Furniture" for the conceptual side, and "Its Endless Undoing" for its undoing.

Pissing on abstraction

Those who blame installations and the lack of the handmade have it wrong. They are distracted by money, and they are looking at old news. The real news is in a return to something simpler, so long as one can mess it up. It is in versions of abstract painting that are not necessarily so abstract or even painting. They are in reflections on Minimalism as it was—and, yes, a Neo-Minimalism somewhere between sculpture and architecture. Matthew Higgs believes in one, and it makes an impressive group show, just a year after a slew of summer group shows about abstraction, with more to come this summer. He also wants to know if it has been that way all along.

"Everyday Abstract – Abstract Everyday" could come out of any number of my own musings on this very page—from Doris Salcedo in Latin America to what other shows have called "Better Homes" and "Everything, Everyday." So could the inclusion of Bill Walton and Bill Jenkins, Tom Burr and Gedi Sibony, or Andy Coolquitt. But Andy Warhol or Hannah Wilke? Could that explain how Higgs has stripped away some choices? He need not think of Coolquitt's colored pole alongside Cordy Ryman or Sarah Sze and Michael Mahalchick, not when that would open the game to formalism, installation, or gross-out comedy. He need not place Walton or Jenkins alongside Ted Victoria, not when that would open the everyday to Surrealism.

Higgs does not go in for pairings. Coolquitt's pole leans way across the room from a 1988 flange of broomsticks, by Al Taylor. Rather, he lets one find one's own pairings and with them a genealogy. Step from Warhol's 1978 piss paintings to Tony Feher's 2007 oil stain on plywood—and from there to the black traces of David Moreno's Television Noise. Step from Ernst Caramelle's 1991 geometric abstraction of simply paper exposed to the sun to Michel François's twelve feet of light blue paper. Step from Wilke's 1975 chewing gum on rice paper to Wolfgang Breuer's 2009 leaves taped to the wall, then to Paul Cowan's bare wisp of fishing lure on stained canvas or Amy Yao's arrow, its feathers and arrowhead really bits of newsprint.

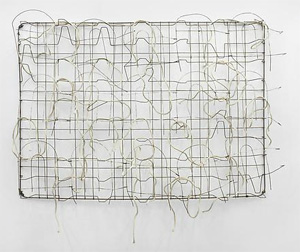

Each genealogy recasts the sleekness of found objects as raw, human, and physical. It makes sense for Higgs, who once championed the Young British Artists in all their piss and elephant dung, before deriding those who blindly follow wealthy collectors, hoarders, and art advisors and before coming to America as director of White Columns. It explains the choice of baled and tied fabric, by Judith Scott and Shinique Smith, or Burr's folded and tacked t-shirt, as His Personal Effects. It explains Ann Cathrin November Høibo's bronze cast of instant noodles or Michael E. Smith's frying pan, holding plastic toy whales melted, perhaps, by the pan itself. It explains N. Dash's print of tangled fibers, like the interior of a vacuum bag, or Alexandra Bircken's loose-knit frame of what looks like bedding. With Jenkins's actual bed springs interlaced with a rope and fence, one may wonder if a fence is masquerading as the comforts of sleep—or a busted bed as the firm boundaries of a fence.

Where there is appropriation, there must also be commerce. Already in 2005, Sergej Jensen glued currency to canvas, now a renewed challenge to the value of art or the euro. Walead Beshty mimics a FedEx box in polished copper, with proper labels. Jason Loebs leaves out a roll of Kodak paper in its shipping box, familiar enough by now to artists who can print anything to any scale and resolution, if only they can afford it. A similar challenge lies in the inclusion of art's master of invisibility, David Hammons, or in the show's oldest work of all. In the early 1970s, a little-known black artist named Philadelphia Wireman bundled rubber bands with a McDonald's pin.

One may wonder at the gestural abstraction of Josh Smith, for all its claims to something more like a readymade. One may wonder at omissions, like other assaults on gesture beyond light and piss, in Philip Taaffe and John Bauer. One could move from the TV test patterns to Scott Reeder's paint over pasta or from crumpled and straightened paper to illusion and ironing in Tauba Auerbach and Sam Moyer. One could easily leap to David Reed, for virtuoso brushwork with the look of photography, or to Jacob Kassay and other abstract exploiters of photography's "strange magic." Such questions always come with a large summer show and a large, slippery theme. They also suggest just how much play is left with the abstract and the everyday.

Furnishing a definition

Almost beyond play, the art of simple things has become a wilder and wilder show. And with new takes on Minimalism, everyday objects, like soap for Karla Black, have merged with upscale design—and the raw materials that go into it. It makes sense, then, that one summer group show goes back to basics. "Furniture" sticks closely to its name, even without the chairs of Joseph Zito. Gareth Long even supplies the office desk, with handy indents for two to share. Not everything, however, functions quite as planned.

Even going back to basics may get complicated. In 1965, Joseph Kosuth displayed the life-size photograph of a standing lamp, its dictionary definition in another photograph, and (oh, yes) a lamp. One and Three Lamps offers representation, text, and object. And each stands as construction, sensation, and reality. As for function, especially after fifty years, or context, like an easy chair, forget about it. If that seems as dry as dust, it is Kosuth, and it was a German in the heyday of structuralism.

It also marks a real point of origin for conceptual art (among many), but there, too, times have changed. Not one other artist in the show leaves things untouched. Long's plywood and steel does serve as a desk, and a handsome one at that—but without drawers. I have a feeling the dealers will be glad to let it go. Long's title for the desk alludes to Gustave Flaubert's Bouvard and Pécuchet, two clerks who turned their job of copying into the pursuit of universal knowledge. For "Furniture," too, the universal remains out of reach.

Paul Gabrielli begins with the store-bought. He sticks an air freshener onto a smoke detector, the end of its copper wires stripped and pointing up. The two disks, as simulacra and asymmetry, have lost the ability to freshen or to alarm, but not to threaten. Megan Marrin covers actual shutters from the fabled Chelsea Hotel, making the work officially arty and artless. She combines the kind with slats and the blank kind, like a cabinet door—but both sealed shut once and for all. The covering, leather, has certain connotations of its own, and objects here are both sensual and disturbing.

Three works refuse a resting place. William Stone's maple chair has somehow brought its two legs together, as if out of modesty, and it seats itself on a block. His larger chair squeezes uncomfortably between its arms and legs, poised like picture frames. Diana Shpungin's chair lies as if knocked over, the tip of each black leg wrapped in white surgical tape to blunt injury and impact. After so spare a display, it may seem obsessive to clean up, but Shpungin nestles kitchen sponges into a shelf of drywall and sea shells, alternatively supportive and porous. Gabrielli adds a mop created from cotton thread.

A less Germanic mind could take the theme in all sorts of directions. Just up the street, Sean Kennedy lays housewares on glass shelves too high to mount, except perhaps by Chadwick Rantanen's floor-to-ceiling poles. And "Furniture," too, relies on real materials, real things, and (with a nod to Jacques Lacan) real desires, but mostly to frustrate them. These artists refuse a functional past or future. Christopher Chiappa's chef's knives, knockoffs of Sabatier knockoffs all but up to fifty-six inches long, lie blade up. In pursuit of conceptual art, look but do not touch.

Minimalism as relic

To enter "Its Endless Undoing," one must pass a gate. Not that Dominic Nurre's hinged steel presents much of an obstacle. It looks as much like an upscale towel rack as anything, and in fact it holds a towel, already somewhat soiled. It might come from the same store as Martin Oppel's floor tiling of tan and white sand—at once earthworks, Carl Andre, painting, and contemporary home furnishings. Sometimes he insists that one walk on it, and much of the time he insists that one does not. I left before the opening, without so much as a beer, half afraid to share in its destruction.

And so things run, between barrier and point of entry, mass-produced and personal, tactile and staining. Like many others right now, the show revisits Minimalism, but through everyday objects on a modest scale. Like others, too, it insists on their ragged edges and associations with physical decay. Compared to these other summer group shows, though, it has a greater mass and a greater chill. While part of a reaction against overblown installations, it approaches an installation itself. On first glance, it could all belong to one artist.

And so things run, between barrier and point of entry, mass-produced and personal, tactile and staining. Like many others right now, the show revisits Minimalism, but through everyday objects on a modest scale. Like others, too, it insists on their ragged edges and associations with physical decay. Compared to these other summer group shows, though, it has a greater mass and a greater chill. While part of a reaction against overblown installations, it approaches an installation itself. On first glance, it could all belong to one artist.

The obstacles do not start with the gate. Before that comes the show's title work, three screen prints by Cody Trepte that give the illusion of an illusion. He seems to have used pencil for shading, with the text modeled as if etched into a clean sheet between two sheets of folded paper. Inside, Lauren Seiden's actual graphite builds its layered geometry to the point that paper looks like rough sheets of metal. One work could be part of the process for making or unmaking the other. The endless undoing could be the artist's or one's own.

The obstacles do not end there either. By the back wall, Nurre sticks together contrasting metal rods into an easily breached horizontal barrier, and Sreshta Rit Premnath leaves a wall-sized exit sign. At least it starts that way, although it turns out to spell EX / X. It plays on two forms of absence, the no longer present and the sign, but its browns arise from abrading photography—and thus the artist's physical presence. Sebastian Black continues the play on symbols and geometric abstraction with letterset paintings and a small floor sculpture. And Nurre's horizontals lead to Larry Bamburg's chilling verticals, made of bones that stack so well because different mammals have different sizes.

Maybe Minimalism is itself a relic, now that art keeps digging up its late modern past. Right on the way in, Richard Evans anticipates its creepy side. His two works combine wax, guitar strings, plaster, metal plates, and a coconut shell into something cryptic, fragmented, self-contained, and threatening to spread. Premnath plays on Minimalism and human remains in another way, too, with the single largest work. She wraps blue tarp around what one might mistake for an industrial exhaust. It is the base of a fallen statue, one arm raised in self-aggrandizing salute.

Not everything works, like Jonathan Peck Abject Biography of found objects sprayed black, from a basketball to one more tribute to Polaroid's obsolescence. Not everything quite fits either, including Colin Snapp's blurry photo from Morocco dumping a cigarette, although he does combine the detachment of a tourist's or artist's gaze with another sign of bodily pleasure and decay. Naturally Minimalism got there first, too—and not only to leave its remains. It held one off with its geometry, and it invited one in to complete the theater or to enact its undoing. Not just with Dan Flavin as collector, delighting in the Hudson River School, it is also looking better all the time. Art's distance from the past gives them both immediacy.

"Everyday Abstract – Abstract Everyday" ran at James Cohan through July 27, 2012, "Furniture" at Invisible-Exports through July 28, Sean Kennedy and Chadwick Rantanen at Untitled through July 31, and "Its Endless Undoing" at Thierry Goldberg through July 15. I start this article with links to related reviews about abstract and related art, because there are so many, but I also return to summer group shows in several years including their baggy themes in 2013, a step outdoors in 2016, and concise themes in 2017..