The Great Beyond

John Haberin New York City

Hype and Hokem: 2023 in Review

With art, it always pays to take a second look—and to keep looking. That means looking beyond the hype, and this site looks again along with you. My 2023 year in review goes beyond the blockbusters, to look for more.

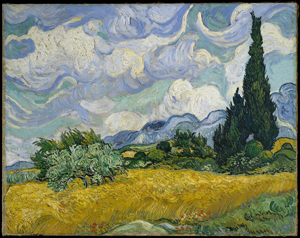

Criticism, I like to think, can be about more than judging. Still, a year's best entails quick picks. That is why I am embarrassed yet again to attempt one. And some of the year's best were blockbusters, with lines to match. I waited over an hour for "van Gogh's Cypresses," and it was worth it. So start with the obvious, before looking deeper—to the birth of modern art, what the quick picks miss, diversity and history, and the institutions that sustain it all.

Is it Modernism yet?

Blockbusters always come with hype and hokum, and why not? Shows like these are costly to put on, while bringing in big money, and "van Gogh's Cypresses" is no exception. Does it really matter that some pictures include a certain tree? Maybe not, but the Met looked freshly at not just Starry Night, but the fatal last years of Vincent van Gogh. It also brought home his close connection to his brother, Theo, a dealer and his greatest supporter. Never mind that it came with an upbeat ending that no amount of great art can warrant.

And then in no time the lines were back for "Manet / Degas." Can even a blockbuster sort out two creative minds and big egos? Maybe not, but it could still begin with Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas on their meeting in the Louvre and end with their envisioning Paris and politics through the lens of old masters and present-day ideas. It should have anyone continuing on to the Met's galleries for European art, open again after the "Skylight Project." It, too, comes with hokum, between loaded themes and forced interruptions for contemporary art. Still, this is the heart of a great museum.

Down in the Lehman wing, the Met jumps ahead to Fauvism and "Vertigo of Color." It, too, has a dubious narrative, of just two artists and one summer—and it, too, is an all-male preserve. Still, if you never understood what brought Henri Matisse and André Derain together and how they differ, here you can. The show also returns to the role of painting out of doors in the creation of modern art. So, for that matter, did "Into the Woods," French landscapes at the Morgan Library. Whose woods these are I only thought I knew.

Same goes for whose Modernism. Can Manet, who stood just outside Impressionism, and Degas, often seen as Post-Impressionist, point ahead to modern art and Pablo Picasso? As it happens, this was an anniversary year for Picasso, and museums all over the world competed to give him a really big show. So did at least one posh gallery, Gagosian, with documentation to match. The celebration included some lemons, like a comedian's put-down of Picasso in Brooklyn, and revealing sidelights, like his early days in France at the Guggenheim. Yet they should already have one looking beyond the blockbusters.

My own favorite sidelights told of how Cubism never made it to a townhouse in Brooklyn—and how a stay in Fontainebleau led to two of Picasso's most famous paintings. Like Matisse's Red Studio last year, they suggest the importance of place—and a decent place to work. They also continue an exploration of when to declare art modern and what it took to get there. So did a show at the Morgan of Blaise Cendrars, a French poet, and his collaborations with modern artists. Oh, and how did America enter the picture, and when did Modernism become abstraction? MoMA looked for answers to both to Georgia O'Keeffe.

Is a return to so popular a painter just more of the same? Up to a point, although it stuck to her drawings. Besides flowers, it also held patterning for its own sake and views from an airplane window onto the earth, with its rivers, roads, and fissures. Like a true American, O'Keeffe took to the highway, only from above. I could not shake it out of my mind when I caught Chris Gallagher this fall at McKenzie on the Lower East Side. He does not need to look past the window itself for abstract art.

Times, places, and media

How then, to go beyond the blockbusters? Of course, the answers are clichés, which means that they are obviously correct and obviously wrong, but start with what they get right. For starters, look beyond the trends. Not all painters today are into mythmaking and their own bodies. Geometric and gestural abstraction still matter. I did not find the words to review Gallagher, Judith Godwin from postwar years at Berry Campbell, David Novros with his still bold Minimalism at Paula Cooper, or Allison Miller with colliding conventions at Susan Inglett—but I did keep returning to what in such variety will last and what will end up in the trash, and I shall let you follow the links to see.

Then, too, look beyond the hype. That can be especially important with new media, which boast of the latest. At times it could seem that technology is taking over from the artist, like AI for Refik Anadol at MoMA. Video also has the advantage of shouting the loudest and flashing the most lights, like Jacolby Satterwhite in the Great Hall of the Met. Yet Satterwhite and "Signals" at MoMA showed only how much their own narrative leaves out. Artificial intelligence, like the natural kind, can look awfully dumb.

Then, too, look beyond the hype. That can be especially important with new media, which boast of the latest. At times it could seem that technology is taking over from the artist, like AI for Refik Anadol at MoMA. Video also has the advantage of shouting the loudest and flashing the most lights, like Jacolby Satterwhite in the Great Hall of the Met. Yet Satterwhite and "Signals" at MoMA showed only how much their own narrative leaves out. Artificial intelligence, like the natural kind, can look awfully dumb.

Third, look beyond the times, places, and cultures you know. The Met exhibits both early Buddhist art and Byzantium. In the process, it challenges not just Europe, but the very choices that western art has made. With Byzantium, it relocates the time between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance to Africa and the Middle East, as an evolving dialogue between cultures. Realism or the inhuman, the dark ages or light? Who cares?

Last, look beyond today's favored media. Not everyone is competing with the past in oil or claiming the future for computer art. What about, say, photography? The fall art fairs added Photofairs New York for just that. The Met followed Berenice Abbott to a city of skyscrapers that you may never have known. Galleries challenged New York to integrate the strangeness of Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander as well.

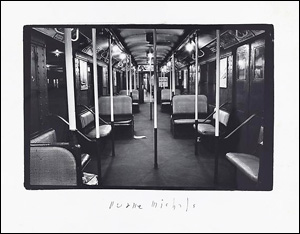

Duane Michals, too, flourished in an empty city, but a city of artists. His portraits of Andy Warhol and René Magritte at D. C. Moore had me wondering if he had substituted actors, but no. Warhol looks young and unfamiliar because he was—and still creating his image. With excursions into photography by Jay DeFeo at Paula Cooper, a time and place proved as elusive as abstraction. The International Center of Photography was at its best, too, with the one-on-one between a photographer and a sitter. It sang of "Love Songs" and the artist portraits in "Face to Face."

ICP ended the year with "Immersion." It takes an artist's residency abroad as neither home nor away. Is this the immigrant experience? Yes, but only in part, and that shows the limits of my own clichés. After all the art of immigration and displacement is fashionable, too. My very call to look beyond the trends is a call for diversity, which is trendy as well, so turn next to that.

A museum's mission

Diversity itself has a diversity easy to overlook. Does it call for other cultures, as a good in themselves, or will it remember the rifts in a life? Pepón Osorio recreates the communities he knows in packed, vivid installations, but with real doubts about who bears responsibility—and for what. Also at the New Museum, Tuan Andrew Nguyen cannot exclude the United States from his account of Vietnam. Unexploded shells still litter the landscape. They also serve as the material for sculpture modeled after Alexander Calder and ring out as bells.

Diversity calls for attention to women, past and present. Does that mean mythmaking after all and felt bodies? David Zwirner presented the latest mythic narratives and wild casts of characters from Dana Schutz, among the year's very best. At the Guggenheim, one could head up the ramp from Gego to Sarah Sze, where sculpture in suspension becomes chaos—or head down to the Whitney for another abstract sculptor in wire, Ruth Asawa, and a different kind of inheritance. Or check out the Jewish Museum for Marta Minujín, like Gego a South America who left her mark elsewhere. Here the collision of cultures leads to everything from soft sculpture to a night in Central Park.

Black artists showed a still greater diversity. Sure, there was portraiture as personality and politics, in the work of Henry Taylor at the Whitney and Barkley L. Hendricks at the Frick. A two-gallery show of Bob Thompson, one of my top picks, made that a claim to the entirety of western art. Yet Sam Gilliam in his last years revisits both his past work and black abstraction, at Pace. And the Met situated a black artist fully in art history. Juan de Pareja, the slave who sat for and traveled with his master, Diego Velázquez, becomes a leading painter in his own right in Madrid.

Does that entail looking beyond the hype after all, to a wholly new history? For truth to the past, look to museums that remain true to themselves. While blockbusters can put money above mission, the Frick does not. It has its shares of bows to contemporary art, but its finest loan goes back to the Renaissance discovery of painting in oil. Three Philosophers by Giorgione hangs across from the Frick's own Saint Francis by Giovanni Bellini, as it may have in a Venetian villa five hundred years ago. They become dual enigmas and dual studies in Italian light.

The Frick must still rethink its mission, as it wraps up its time at the Frick Madison and prepares to return to its mansion, renovated and expanded. Other institutions must do so with every show. The Morgan has no qualms about contemporary art, although I have my doubts. Still, two shows focus on its founder, J. P. Morgan, as a collector of Bibles and an heir to medieval money. That may not say everything you need to know about money in art today. Yet they sure come close.

The Jewish Museum must feel the need even more, with a new director and a contested conscience. Can it be both a museum of Jewish heritage and of cutting-edge art? This year it displayed the Sassoons, a family of collectors divided over both. Minujín, for that matter, is the daughter of Russian Jews in Buenos Aries and a self-styled citizen of the world. She also has enough irony to cast doubt on them all. Like diversity and trends, identity is a challenging and changing thing.

Of course, this site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at length. Dates and locations appear with fuller reviews, with links in this wrap-up. I did not review several more because of past reviews, although I have regrouped them where they appear for a fuller, more independent picture of the artist. You can now also see year-end reviews for 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022.