Best Wishes

John Haberin New York City

Beyond the Big Boys: 2010 Art in Review

As another year comes to an end, everyone makes a show of disdaining "best of" lists, and everyone indulges in them. I guess that goes with the idea of the best: just one of those things.

I should be the last to list my top 10 for 2010. After all, I aim for a kind of criticism that is about more than thumbs up and thumbs down. If halfway through a review you are not sure whether I like the work, fine with me. As long as you know what I think, and the thought contributes something to the art. Then again, that makes it all the harder to resist (as in 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2012) weighing in.

But does that have to be mean just listing ten shows? Like last year, call it instead an excuse for the year in review. This site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at greater length. In my own way then, hold your breath and count to 10.

10. Best dead white males

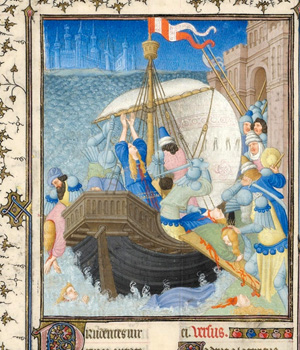

I write about contemporary art, but my heart is in art history, especially the reactionary Western version. It in fact informs my annoying approach to criticism, trying to bring ideas together with specific artists, exhibitions, and interpretations—that uncomfortable middle ground between New York magazine and October, like an ordinary classroom. And this year had some of the biggest, best, and deadest, with Abstract Expressionism at MoMA, Henri Matisse in wartime, or late Monet in Chelsea. The first, continuing last year's trend of creative uses of a museum's own art in a recession, even includes an African American and many of the women that MoMA hesitated to collect. However, I vote for the Limbourg Brothers, who died halfway through an illuminated manuscript that helped invent the Northern Renaissance. The Met displayed their major completed work, which already wrote the book.

9. Best sons and lovers

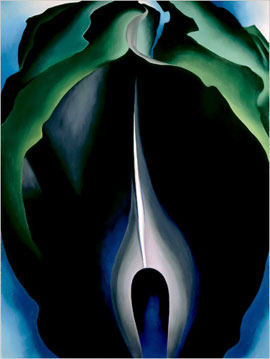

Of course, not every artist is dead or even white and male, and (pace Harold Bloom) not every creative act is an oedipal struggle. Alix Pearlstein made every emerging artist's anxiety into a haunting video, and Kate Gilmore showed what really happens when one puts women on a pedestal. Surely the best father-son event spanned two shows, two months, two cities, and two artists who like each other's work quite well, thank you—with Robert Ryman at the Phillips Collection and Cordy Ryman at DCKT. Four galleries in Chelsea and nine on the Lower East Side set aside their own rivalries for two gargantuan summer shows, one on Southern California and the other on a fictional crime scene. As for lovers, while the Met's time line of Modernism ran as "Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand," Stieglitz's greatest discovery was female.  In a year rich in varieties of contemporary abstraction, Georgia O'Keeffe at the Whitney topped them all.

In a year rich in varieties of contemporary abstraction, Georgia O'Keeffe at the Whitney topped them all.

8. Best photography

I never thought I would care enough or know enough to write about photography, but it keeps adding up to some of the best exhibitions in town. It offers new models for abstraction, as with Jason Tomme, Scott Lyall, and Sara VanDerBeek. At the Whitney this year, VanDerBeek reflects on photography's very claim to remember the past. Other standouts include insights into the divisions within South Africa by David Goldblatt and Zwelethu Mthethwa, Claire Pentecost seemingly trapped in her studio. I cannot swear he is better, but Lee Friedlander is at least the most ornery. He also had two shows, with gnarly landscapes at Mary Boone and "America by Car" at the Whitney.

7. Best show I neglected to review

I could blame myself, but I have a day job and do not get paid for this. Besides, omissions come with my idea of a good critic—who, like Mr. Ed, will never speak unless he has something to say. I neglected worthwhile exhibitions by painters too numerous to mention. I passed on Roxy Paine and early Dan Flavin in color, because I had written about each of them more than once before. However, each was a standout, and Flavin's wall of light transformed Paula Cooper gallery, by adding and subtracting colors as one walked from one side to the other. Best of all, Lee Krasner from the 1950s brings back the days when Robert Miller displayed Krasner's autumnal color in the Fuller Building, and I can still smell the hair salon down the hall.

6. Best regretted

Rivane Neuenschwander is a contender for biggest disappointment, as the colorful and delicate surprises of her 2006 installation gave way to a leaden retrospective. However, not everyone can withstand to a midcareer retrospective, and everything at the New Museum is leaden. The estate of Robert Rauschenberg at Gagosian can hardly live up to the work in his great retrospective, but then what work of his still unsold could? Nope, the prize goes hands down to Marina Abramovic, for turning her erotic rituals and riveting self-exposure into museum pieces. Still, like the charming self-indulgence of Tino Sehgal at the Guggenheim, she raises good questions about what happens when performance art enters the museum—to be performed by others.

5. Best ignored

Or call this category "biggest annoyance"—and I mean big, although this years versions were smaller than in years past. Increasingly, New Yorkers are learning to hate and fear precisely the group shows that are supposed to define contemporary art. That means the 2010 Whitney Biennial and Greater New York, with its promise of emerging artists. By now they differ from art fairs only in that dealers may soon ignore them, and this year's versions played it safer than ever.  I found the latter the most annoying, however, since it showed all too well P.S. 1's fall from alternative space to a stepchild of MoMA. I sympathize with those who found "Skin Fruit," a museum's sell-out to Jeff Koons and a wealthy donor's collection, a greater annoyance, but one could safely make fun of it.

I found the latter the most annoying, however, since it showed all too well P.S. 1's fall from alternative space to a stepchild of MoMA. I sympathize with those who found "Skin Fruit," a museum's sell-out to Jeff Koons and a wealthy donor's collection, a greater annoyance, but one could safely make fun of it.

4. Best trend

The biggest news is that it is now acceptable to express annoyance. Critics who once gushed over the New Museum's architecture are dubious, and The Times dared to ask whether the Brooklyn Museum had sacrificed art to outreach. Roberta Smith slammed overblown installations at the price of the handmade, Holland Cotter called out last year's crowd pleasure of late Picasso, and everyone pounced on a particularly shallow, flashy display at Gagosian. Exit Art set out a history of alternative spaces, and artists started to question whether they need dealers at all. I hope that next year's trend will be a backlash to the backlash. Instead of taking down the priciest galleries as if they are still the norm, people will start to notice the diversity and drift of art now—and maybe, just maybe, start to forge true alternatives.

3. Best classroom

Some shows may not convince me as art, but they teach me something—far more, say, than critics on reality TV. I still do not know whether to call John Baldessari a prankster or a blowhard, but now I know why he had to break his own promise not to make boring art. Charles Burchfield made attractive enough landscapes, between conservative and modernist, but now I know about his strange decades of recycling his own work. "Chaos and Classicism" will not revive any reputations or rewrite history, but the fascist underside of Modernism between the wars is memorably creepy. However, William Powhida and Jennifer Dalton went them one better, turning the course of an exhibition into a literal classroom, complete with a chalkboard and seminars. Their "#class" insisted that one understand, criticize, and look for hope in the art world.

2. Best housecleaning

Museums everywhere are showing off brighter and airier spaces. It comes with the pressure to expand. It comes, too, with the pressure to serve as a public space for a wider community. With MoMA in 2004 the results were not pretty, but the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts did not do badly with its new wing this year, and I look forward to seeing the new American wing of Boston's MFA in January. The Frick Collection and the Morgan Library did better without even growing, just by careful lighting and restoration of their founders' private galleries from nearly a century ago. Better still, like the Met only months before, the Frick cleaned and displayed its Velázquez portrait along with Spanish drawing, giving a king the illusion of command and white the illusion of silver.

Museums everywhere are showing off brighter and airier spaces. It comes with the pressure to expand. It comes, too, with the pressure to serve as a public space for a wider community. With MoMA in 2004 the results were not pretty, but the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts did not do badly with its new wing this year, and I look forward to seeing the new American wing of Boston's MFA in January. The Frick Collection and the Morgan Library did better without even growing, just by careful lighting and restoration of their founders' private galleries from nearly a century ago. Better still, like the Met only months before, the Frick cleaned and displayed its Velázquez portrait along with Spanish drawing, giving a king the illusion of command and white the illusion of silver.

1. Best mess

Of course, the private sector cleans up on real-estate, too. Housing may have crashed outside of New York, but Williamsburg and Bushwick creep eastward, Lombard-Fried and Zach Feuer traded up in Chelsea, Pierogi finally filed the paperwork to reopen its Boiler, and both Salon 94 and Sperone Westwater grabbed sleek spaces on the Bowery. Remember when gallery-going centered on 57th Street, with what John Russell called "trial by elevator"? Probably not, but Norman Foster insists one use the elevator just to move from room to room at Sperone Westwater. Too many installations look like construction sites anyway, but for once that became a virtue—and perhaps the finest show of the year. With her mammoth but gossamer assemblages of shelves, ladders, milk cartons, Windex, portable fans, stepladders, dead rats, and drafting tools, Sarah Sze takes on the big boys without losing her sense of fragility and wonder.

Lee Krasner continued at Robert Miller through January 29, 2011. Of course, this site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at length. You can now also see year-end reviews for 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023.