Portrait of the Artist

John Haberin New York City

Shunk-Kender and Duane Michals

"The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails." James Joyce's conception of art is central to Modernism. The artist must stay out, and the rest of us, as T. S. Eliot wrote, must not waste time searching out his intention.

What happens, then, when photography takes as its subject the artist? The duo who went by the name Shunk-Kender kept themselves out of their work. They also helped create some of the biggest egos in art, but their staged photos are always a collaboration. Duane Michals, in turn, treats artists and friends as celebrities. But then Joyce's quote does come from Portrait of the Artist based on his childhood, where his hero compares himself to a god. Michals never could.

He did become something of a wordsmith himself. A photo even supplies the words: "there are things here not seen." For decades now, he has been hand lettering his photos, if only with his signature in large, freehand letters. Had he turned to photography for evidence of things unseen? Consider the evidence.

Ego boosters

Even an egotist needs to work with others. Well before big markets and celebrity artists, Yves Klein designated his ultramarine International Klein Blue, but he contributed no more to its manufacture than the idea—and that was before he took a big leap. With his Saut dans le Vide (or "leap into the void"), he played at Superman, arms outstretched in midair while a cyclist continues his daily commute down the street, oblivious to the whole thing. But then a whole team had to catch him before he hit the pavement. Besides, someone had to construct the photomontage to hide them. If anyone worked without a net, it was the photographer.

Make that two photographers, Harry Shunk and János Kender. That day in 1960 marked the start of their collaboration. With "Art on Camera," MoMA gives credit where credit is due. Shunk, from Germany, and Kender, from Hungary, worked as Shunk-Kender, first in Paris and then in New York. To believe the curator, Lucy Gallun, they may well have helped to mold the artistic identity of more than two dozen others. Who knew?

Collaborations and the avant-garde are messy things. One could just as well credit Klein for creating them. Then, too, the one-room exhibition boils down to just two other projects. In 1968, the photographers assisted Yayoi Kusama in performance. She had nudes join her at the stock exchange, in the first true "occupy Wall Street." Then they covered one another with polka dots, much like her installations.

Shunk-Kender were connecting the dots between "happenings" and art. They were also defining her gesture as not just an overgrown child's birthday party. They did so by juxtaposing the two scenes, in the sobriety of black and white. The same devices go into a more extended project from 1971, conceived and organized by Willoughby Sharp, in which twenty-seven artists took over a pier in Lower Manhattan. Here the emphasis lies on performance's ties to Minimalism and conceptual art. Together, the three projects draw on six hundred photos from the Shunk-Kender Foundation that have entered MoMA's collection.

Museums usually credit each image to the more familiar artist, but who came up with what? Mario Merz, for one, allowed the photographers free rein. They do so progressively, in stills arranged like contact sheets, so that his signature dome structure is just coming to be. Yet the arrangement also suggests a collage as an independent work. Other photos belong more to the performer, but there, too, Shunk-Kender have their say. Pier 18 could serve as a staged textbook of that decade's art.

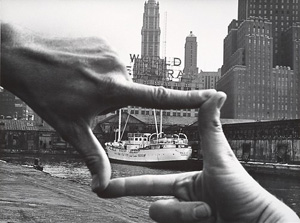

John Baldessari, ever the conceptualist, frames the pier with his fingers, while Richard Serra, Dan Graham, Vito Acconci, and Keith Sonnier give it geometric form with their performances and "negative spaces." William Wegman uses it as a bowling alley, while Jan Dibbets, known for a memorial to a French astronomer, adds it to his "progression of the future." Mel Bochner measures the river, while Gordon Matta-Clark dredges it. In truth, celebrity artists nowadays need whole factories of collaborators to keep up with the market, and critics tie themselves in knots to treat basketballs in a fishtank by Jeff Koons as an original engineering feat. But then Shunk, who died in 2006, and Kender, who died in 2009, are no longer around to document it.

From portraits to stories

For Duane Michals, every picture tells a story, portrait photography included. The Carnegie Museum of Art calls its retrospective "The Storyteller," for all its strength in portraiture. His camera is never at home apart from people, and his subjects are never alone apart from an idea. He spells it out, too, in his endearingly clumsy handwriting—often in block capitals, in the broad margins of his black-and-white prints.  Sometimes he indulges as well in overlays of color, applied by hand, that obliterate or enhance hands and faces. The device recalls Cubism, but just as much the sheer possibilities of the medium.

Sometimes he indulges as well in overlays of color, applied by hand, that obliterate or enhance hands and faces. The device recalls Cubism, but just as much the sheer possibilities of the medium.

Born in 1932, Michals had his last New York retrospective way back in 1970, at MoMA, and the one in Pittsburgh takes him, like LaToya Ruby Frazier, to his roots in steel country. New Yorkers will have to settle for a visit to Chelsea. There a large selection of photos, all from hitherto unprinted negatives, plays up one side of the equation, as "The Portraitist." It cannot help telling stories all the same. Are those stories more simplistic than one willingly remembers? Where a show the year before had him prowling the city, like Danny Lyon, Gordon Parks, or Thomas Roma, here he seems content to sit still.

His marginalia does start to get in the way of his portraits. "Jeremy Irons bares his soles," meaning the soles of his feet, and Liv Ullmann is "deeply feminine." Johnny Cash, hand raised warily over his mouth, "was hotter than a pepper sprout." Paul Taylor, the choreographer, is "dancing cheek to cheek"—or rather lying cheek to cheek with his beagle. "Just when you've been Leibovitzed there is no going back." They lie between one-liners and advertising slogans, but then Annie Leibovitz, the photographer for Rolling Stone covers, knows something about PR herself.

Like her, Michals has done his share of commercial photography. He was good at it, too. It enters in brooding images of Dustin Hoffman and Martin Scorcese. It takes on artists as well, including Balthus, Charles Burchfield, Andy Warhol, René Magritte with his bowler hat, an aging Marcel Duchamp, or a young Jasper Johns. Those who write off Magritte for his Surrealist one-liners will see only the obvious, just as some write off Jasper Johns for copying himself. But are they right?

Celebrity portraiture colors even the artful overprinting. A redoubled Philip Roth on the occasion of his best-seller, Portnoy's Complaint, looks like a star. Multiples of Barbra Streisand play up her gestures and her jewelry. Sentiment enters for Michals even in his most personal stories. "Jack," hands raised above his head, "died of AIDS. He cried himself to sleep alone."

They are haunting all the same, like a photograph of his mother after his father died. Honesty matters, as with John Cheever in a cast. Gay themes are muted but real. Michals worked for fashion magazines, but he displays little concern for fashion. He even mocks fashion by posing like Cindy Sherman in a wig. His borders may recall Richard Avedon, but he has none of Avedon's striving for iconicity. In his busiest years, he did not even maintain a portrait studio.

Which stories are conventional, and which are honest? Surely all are both. Eugène Ionesco bares his chest, as an act of exposure, like Pablo Picasso showing off at the beach. With Death Comes to the Old Lady, the title is a cheap pun on an old Willa Cather novel—but the lady sits dispassionately, face forward, and her death is real. Like Robert Mapplethorpe, Michals links portraiture and testimony, although he is rarely startling or confrontational. "This photograph," he writes, "is my proof." He punning, but he means it.

Evidence of things unseen

Michals had turned thirty when he added text to the photograph of a diner from 1964, some thirteen years before. Words had been long in coming, since who after all would ruin a perfectly good image that way? No wonder, then, that they poured out in a welcome stream. Not all of them described the invisible at that. He wrote of the taste in his mouth, but also the roach crawling across a stool. Implicitly, he was writing about an early morning encounter that few would trouble to taste or to see.

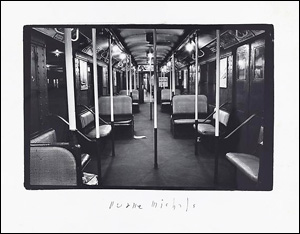

Sure, Michals had supported himself on commercial assignment—for Esquire, Mademoiselle, Vogue, and more. Yet it hardly troubled him at that, not when it freed him to turn his camera on an unseen world. He rose early in 1964 to discover an empty New York of newsstands, Penn Station escalators, subway cars, laundromats, and cobblestone streets, one more spacious and welcoming than the next. A slideshow plays outside his retrospective, alternating with a recent turn to film. When it comes down to it, he always thinks in series. Rising early makes sense as well for someone who instinctively gravitates to the light.

He did so when he photographed The Illuminated Man in 1968, head and shoulders dissolving in a glow. He did so, too, with three shots of Andy Warhol becoming progressively a blur. In a fourth shot, Warhol disguises himself with merely his hands. As a gay Catholic from steel country like Warhol, Michals would have known the virtue of disguise. And disguise came easily to his subjects—like a door for Joan Didion, an easel for René Magritte, and antlers for his life companion, Fred Gorey, as he "wandered ito the woods looking for love." As the lettering for a man caught between a bathroom and deep space puts it, Things Are Queer.

Michals recalls a photographer with an even greater gift for words, Lewis Carroll. The Morgan gives him the run of its collection, to weave others throughout, Carroll included. He turns out to have a talent for curating. It is only a short step from Alice's tea party to another child's party—or from William Blake, the Pre-Raphaelites, Egon Schiele, and Surrealism to New Yorker cartoons and Mickey Mouse. The Morgan also groups the photos thematically, to stress his storytelling. A man tunneling into a hall of mirrors "is telling a story about a man who is telling a story."

The ten sections sound awfully pretentious—"theater, reflection, love and desire, playtime, image and word, nature, immortality, time, death, and illusion." Yet the stories stay close to earth. Gorey enters as a stag, but he starts with his head on a pillow next to a single bee. Michals spends one sequence, Illusions of the Photographer, tinkering with his lens on the sidewalk, and it lends its title to the show. He also uses the heavy-sounding "love and desire" for memories of home, including mill, hills, and burlesque house. He still imagines his father promising to write with "the place where he had hidden his love."

He imagines a conversation with God, but both parties look equally human and sound equally unwilling to cede ground. Which says, exasperated, "You don't even know that you don't know"? He describes the soul departing from the body as a product "recall," but he does not have to believe in magic to experience it. He photographs Warren Beatty, the year of Bonnie and Clyde, with a hotel curtain rising as a stage curtain never could. In memories of industrial Pennsylvania, "I thought all rivers were yellow and all nights were orange," and why not? He could only "feel sorry for those children" whose "nights were only black."

"Shunk-Kender: Art on Camera" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through October 4, 2015, the latest polka-dot house by Yayoi Kusama at David Zwirner through June 13, and Duane Michals at the Carnegie Museum of Art through June 2 and at D. C. Moore through March 21. Michals returned at The Morgan Library through February 2, 2020. A related review looks at Duane Michals and others in an empty New York.