The Last Word

John Haberin New York City

Off the Record and Gregg Bordowitz

How do you remember the 1970s? If you are old enough, you may remember the headlines—of Watergate, stagflation, and wars hot and cold. Or you may remember instead only images, of scowling generals and bellicose state leaders.

Sarah Charlesworth pictured it just that way even then. She eradicated everything but a newspaper's masthead and photos for, she believed, the very picture of militarism. At a time of critical theory and distrust of Modernism, everything in art came with a subtext—but not all of it was on the record. A small show at the Guggenheim Museum remembers when art looked behind the scenes, to a not so peaceful coexistence between images and text. For the thirteen artists in "Off the Record," with works from the museum's collection, you can hide or bury the truth, but you cannot kill it so long as there is art. Given the truth, that is not necessarily an optimistic conclusion.

Not all that long ago, text had the job of sustaining art, because (serious people liked to say) painting is dead. Now practically anything goes. Back then, though, everything most definitely did not go. It did not go in 1977 for Charlesworth, even if you have trouble believing in her means or her message. It did not go either for Carlos Motta in 2005, with a long history of imperialism that museum-goers can take home. Art then, the Guggenheim wants to say, had an urgency that painting today often lacks.

Gregg Bordowitz could hardly agree. Even now, he has to confront one of the time's most terrible issues. More than halfway through his MoMA PS1 retrospective, Bordowitz himself enters the picture, still alive and acting up. Just after photos of AIDS activists by Tom McKittericks, there he is, too, in a photo by Lee Snider. He was only maybe twenty-four, but he may need the urgency of a microphone and the solidarity of a protest to sustain his youthful energy. Even then, he was hanging on for dear life.

He is to this day, letting others tell their stories but always having the last word. He was there with the ACT UP movement from the first, and he made his name in video, with others on-screen. They might be young African Americans asking for love or those with AIDS recounting their experience. In a show called "I Wanna Be Well," he sounds desperate enough, but he is only quoting the punk energy of the Ramones. As a video has it, Fast Trip, Long Drop. Now if only he could sustain it.

Not everything goes

To my mind, painting was never dead, but then art is not so easy to kill. In the very depths of the Great Depression, Walker Evans left an unforgettable record of its costs, with his photos of sharecroppers and homesteaders. Not every loss, though, made it into the public record. Evans insisted on it, too, when he took a hole puncher to his unprinted negatives. Lisa Oppenheim has other ideas. She prints from the negatives anyway, for all that they might reveal—and then, for good measure, she prints the holes as a near-abstract equivalent to scarred landscapes and lives.

Art after Covid-19 can seem like a perpetual celebration. That may sound like an odd thing to say, with museums all but empty and so many galleries closed for good, but painting is back with a vengeance. (Then, too, at least in an empty museum you can get closer to the art.) Today's focus on diversity is a celebration as well, with such Latin American artists as Carlos Motta. Even in a show of political art with "An Emphasis on Resistance," rest assured that people resist. Glenn Ligon seems to agree when he copies over and over a line from Jean Genet, "We Are the Ink That Gives the White Page Its Meaning."

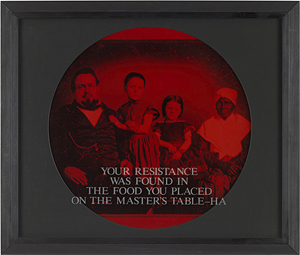

Not everyone at the Guggenheim, though, is celebrating, least of all African Americans like Ligon. Hank Willis Thomas may appear to be, with images of the black middle class—and with titles like Something to Believe in. Hank Willis Thomas, though, clips his glossy photos from magazines, to ask, in his series title, whether anything can remain "Unbranded." Lorna Simpson pairs a black woman with an African mask, taking obvious pride in both, but a mask is also for hiding, and she photographs the woman from the back. Carrie Mae Weems cherishes and savages stereotypes, too, in adding color to old prints and with text etched on glass. When Adrian Piper depicts monkeys in a game of "see no evil," she asks every black to Decide Who You Are.

Ligon adopts Genet's title as well, Prisoner of Love. One can be both loving and a prisoner, and his text all but eradicates itself, dense and smudged in oil on gesso. I could not quite make out images of Freedom Riders on marble dust and vinyl by Tomashi Jackson, but he wants it that way. They look suggestive enough as it is, paired with campaign buttons and ballots, across eight feet of reflective blue. Still, do images like these speak loudly enough for themselves? Are they even on the record?

What, too, does art mean by the record? Sadie Barnette obtains FBI files on her father and the Black Panthers, but otherwise it can mean almost anything, public or private. Artists can reproduce the record or erase it, like Ross Bleckner and Zachari Logan up at Wave Hill this summer with the obituaries—just as the record for them can obscure the truth. Sable E. Smith turns a courtroom hearing into a coloring book, while Leslie Hewitt calls her collage Riffs on Real Time. For her, it picks up from where magazines for Thomas leave off. It looks gorgeous, too, but is it really so urgent?

Art might be well overdue to ask about its limits today. Still, urgency can easily mean an excess of certainty. The show seems awfully nostalgic for Sarah Charlesworth and the "Pictures generation," but without that generation's irony. Sara Cwynar makes an awful fuss about scrapbooks of bananas and the Acropolis. Then, too, the record can look far more slippery than the artists have in mind. Walker Evans was an advocate, not a censor, and no photographer publishes every negative. The actual record is still in progress and always contested ground.

Still dying

Gregg Bordowitz opens with a racecar, recreating Drive from 2002. Bordowitz wants to see AIDS "from the point of view of a race-car driver"—and that is his gift, to adopt other points of view. In text over the entrance, "The AIDS Crisis Is Still Beginning," but it has changed considerably since that protest in the late 1980s. Like the car, he shows his wear and tear, and he is still dying, but with luck he can be dying for a long time to come. He can thanks to an incredibly costly drug program, and the car's rusted surface has its share of logos from the drug companies who make that possible and profit from it. In case you missed the point, it also has a logo for just plain Big Pharma.

Not that he cannot trust you to figure that one out for yourself. He respects other points of view too much. Still, it is too much on his mind for him to shut up. And that is Bordowitz in a nutshell, the listener and the control freak. What of selections from his library in Chicago, to credit those who got here first? (Born in Brooklyn, he grew up in Queens, worked in New York's East Village, and left to teach at the Art Institute of Chicago.) It is enviably serious, thorough, and organized—alphabetically by author within genres like philosophy and poetry.

Not that he cannot trust you to figure that one out for yourself. He respects other points of view too much. Still, it is too much on his mind for him to shut up. And that is Bordowitz in a nutshell, the listener and the control freak. What of selections from his library in Chicago, to credit those who got here first? (Born in Brooklyn, he grew up in Queens, worked in New York's East Village, and left to teach at the Art Institute of Chicago.) It is enviably serious, thorough, and organized—alphabetically by author within genres like philosophy and poetry.

He can make it hard to know where his words leave off and others begin. In the most seemingly personal account, the speaker is an actor and the words from Vladimir Mayakovsky and early Soviet art. A wall drawing brings in David Hume, the philosopher, but to situate Hume's Treatise on Human Nature in a family tree of gay experience. The show includes other artists as well, including Jack Whitten (but not Jack Whitten in sculpture), who inspired Bordowitz's abstract Tetragrammaton, named for the Hebrew substitute for the name of God. A photographer, Lee Schy, contributes his Extended Family Vacation from 1984 as well. It becomes an "intended" and then "overextended" family vacation, not unlike the retrospective.

Words can still betray him. Bordowitz likes the text over the show's entrance so much that it recurs over the entrance to the museum, but can a crisis be "still beginning"? Surely it ought to say that the crisis is just beginning, although that cannot be right, or is not over, although that cannot bear the same weight. The artist also wrote over two hundred one-line poems in 2014, as his Debris Fields. Most sound mistranslated from some other language after connecting words were dropped. He wrote hundreds more, too, and visitors can take home his latest Pandemic Haiku, where they run to due and proper platitudes about climate change and other present disasters.

He has his limits as a man with a message—or maybe a thousand messages. He will never evoke the pain of the AIDS crisis and the raw sexuality of its chroniclers, like Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, Martin Wong, Alvin Baltrop, and Robert Mapplethorpe. The curators, Stephanie Snyder of the Cooley Art Gallery at Reed College with MoMA PS1's Peter Eleey, do not make things easy either. Some videos share a room, like a theater with a double or triple bill. Since they can run up to an hour, it takes doing to get a sense for them all. Still, one can feel the artist clinging to or coming to life, again and again.

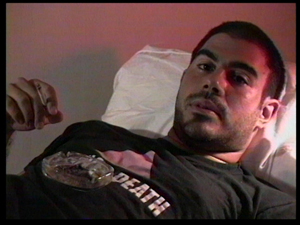

He appears early on, furtive and languid—in a photo by Schy, in a photo booth in Paris, and in graphite sketches with the lazy shorthand of late Picasso. He hits his stride at the microphones. And then, on video in 1993, he takes center stage, besieged by symptoms he cannot understand but only fear, while explosions level cities. Later, he intones what he can, while a song by Morgan Bassichis begs for others to cry out with a shofar, the Jewish ceremonial horn. In sculpture just in time for the show, he hopes for a successor to Vienna's Plague Column, with an angel flying in to save or to kill. I am not betting on salvation, but he would still want the last word.

"Off the Record" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 27, 2021, Gregg Bordowitz at MoMA PS1 through October 11.