After Minimalism

John Haberin New York City

Christian Haub, Richard Nonas, and Jim Osman

Marianne Vitale and Jannis Kounellis

Fifty years ago, Minimalism seemed to have tamed Abstract Expressionism once and for all, but how? Had it brought out the heart of painting all along, in light and form? Had it instead stripped painting of its self-indulgence, anticipating the decade of irony to come? Or had it denied the art object its purity, on a grand scale at that, like installations later still? Was it a dead end or a transition to the postmodern future?

Maybe both, which explains why it has echoes in a more eclectic art scene. It is recognizable both as painting and construction, whether in plastic, wood, or steel rails. For Christian Haub, commercial hardware collects the light.  For Richard Nonas and Jim Osman, simple means take on makeshift structures. For Marianne Vitale and Jannis Kounellis, leftovers acquire weight, space, and a history. Together, they provide a fresh definition of what a past movement may have meant all along.

For Richard Nonas and Jim Osman, simple means take on makeshift structures. For Marianne Vitale and Jannis Kounellis, leftovers acquire weight, space, and a history. Together, they provide a fresh definition of what a past movement may have meant all along.

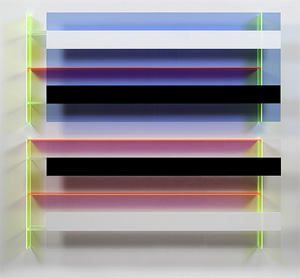

Pure plastic painting

Christian Haub calls his constructions Floats, for they seem to float away from the wall. I like them almost as much for how firmly they hold. Haub constructs them from dyed acrylic, cast or cut into rectangular sheets. A single strip, slipped over bolts in the wall, holds up the art, which can easily weigh twenty-five pounds. The whole gains in mass from its typically vertical dimensions and repeated horizontals, but it looks ever so much lighter—and not just because of one's expectations for plastics. I wanted to lift one off its mount and carry it away.

It looks so light because it collects light, like oils. The work may sound like sculpture, but Haub is still painting. No wonder Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe has compared him to both media, in Charles Biederman and Ilya Bolotowsky. Haub's broadest acrylic sheets play off against narrower strips, which may be opaque or nearly transparent, with the simplicity of red, green, and blue. Both are at once his canvas and his color fields. They also allow a third dimension to the vertical and horizontal fields, like the paper threads by Adam Fowler coming right out of the picture plane—but they are first and foremost colors.

Seeing them as color has its danger, too. One might mistake the hard edges, right angles, and asymmetry for Piet Mondrian in Lucite. After all, Mondrian's movement did call itself Neo-Plasticism. That (or Burgoyne Diller's stringent adaptations of Mondrian to America) would miss the third dimension and the luminous. With Haub, opaque black and white take on a greater creaminess in resin. Strips at right angles from the wall are brightest at their edge, as if lit from within.

Just as important, this painting is not an early modern balancing act, with this strip here offsetting that strip there. It comes well after Pop Art's and Minimalism's elevation of the commercial—and Dan Flavin with his sense of light. Even John Chamberlain moved from crushed auto parts to refraction off Plexiglas, while David Novros uses horizontals like still another rich jigsaw puzzle. It also comes after Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, and Clement Greenberg with his call for the geometry of painting determined by its support. With each color field its own plastic canvas, this is "art as object" in spades. Haub just dispenses with the flatness.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should say that Chris was in my class at Princeton, where I understood absolutely nothing about what he and other painters were doing. (I guess it got me thinking.) His titles effectively dedicate the works to more than one shared interest, often musicians who died too soon—and not, I promise, the music of Broadway Boogie-Woogie. Comparing generations is a little too close to Greenberg's pat march of history, but the show makes a superb pairing with Thornton Willis right on the same floor. Willis's Steps announces the right angles, and he, too, composes in color. Born in 1936, he rebels against formalism in his own way by placing the stepped fields arbitrarily within a canvas.

That rebellion was going around, as with Thomas Nozkowski or Ted Stamm. Haub is at once more rigorous and more comfortable with illusion. (Robert Ryman would have stuck the bolts along the sides, just in case you missed them, and Biederman would have turned the protruding pieces into shelves.) So many right now have found ways to work between painting and other media. Both Scott Lyall and Charles Hinman have drawn depth from a second color along the back of a canvas by the wall, while Becky Beasley has cantilevered black Plexiglas to suggest a physical landscape. Haub by comparison plays the traditionalist, but in full color.

Under construction

Richard Nonas offers two versions of Minimalism, neither one exactly as I remembered it. But close enough, and that matters, too. There is no denying the simplicity of materials, their regular arrangement, their sheer mass, and their remoteness from art with a capital A. Born in 1936, just one year after Carl Andre, Nonas sticks closely to the walls and floor. One can easily imagine lending a hand should they become dislodged. They recall when the word installation meant not an overblown art form, but putting together a show.

That meant putting a show together in real space, the shared space of the viewer. Do not, however, plan to walk on this work, for its own good. Do not plan on kicking it either, or it might hurt. The version on the floor consists of steel of rectangular cross-section. Long bars lay side by side, like Andre's square tiling but thicker and without a sheen, while short ones lay across others of similar dimensions, like the smallest and simplest of arches. When Barnett Newman joked that Minimalism could not get it up, he did not anticipate such a modest but convincing rejoinder.

The version on the walls uses small pieces of wood, again nearly in parallel, but diverging almost of their own accord. The Cherry Tree Split series, from 2011, sounds as if a laborer had just dug in, and Nonas says that, like Remy Jungerman, he came to his art from field anthropology. Works from 2012 use pin oak, like Minimalism as organic growth. The floor pieces then offer an alternative architecture—as if Joel Shapiro and his playfulness had left the wall only a moment before. Nonas calls the show "Ridge," which can refer to landscape or to rafters. He says that anthropology taught him not so much cultural practices as the experience of things in themselves, like Minimalism once more.

Constructions by Jim Osman may be makeshift, too, but never natural occurrences. His smaller works look like failed attempts to recycle wood scraps as picture frames, and indeed an early listing called his latest show "The New Picture Plane." The single large work in "Stack" looks even more jerry-built. Naturally the rough squares do not hold pictures, because they are the picture. The balancing act of attachments, cantilevers, and counterweights even has its own parallel in Mondrian. Some but not all the scraps are painted.

I am not dead sure that the paint job adds all that much beyond a lighter touch. And I doubt that I would like the larger piece as much without the smaller ones as a model. As with Nonas, the elements of a larger structure often take over from the whole. For Osman, with more than thirty years of exhibitions behind him, Minimalism simply had to loosen up. Is the result painting, sculpture, installation, or architecture? One can see the range of possibilities in his titles—Landscape, Gable, Wedge, Boxes, Blocks, and Frames.

Last year saw the recovery of several lost histories of Minimalism and its origins, as with Bill Bollinger. Without question, curators are under way too much pressure to recover neglected artists, just as they are under too much pressure to spot emerging ones. Still, the effort helps engage the present. Younger artists have found their own Neo-Minimalism in everyday materials. Where Allyson Vieira treats an installation as deconstructive architecture, though, Nonas and Osman are still constructing. They are also still under construction.

The Low Line

Call it the Low Line, because it brings Chelsea back to earth. When Marianne Vitale and Jannis Kounellis lay railroad tracks through a gallery, they connect a former shipping and manufacturing district to its past, while leaving implicit other histories. Vitale is sparer and cleaner than ever, while Kounellis prefers layers, fragments, and rough edges. She all but eliminates narratives, while he can hardly get enough of them. She gives the space a unity one never noticed before, while he keeps one stumbling on obstacles and half-hidden corners. Both leave one to find one's own history in stepping over or around the art.

Less than eighteen months ago (and in a model the year before), Vitale's Burned Bridge already crossed the gallery. That does not sound like much time between shows, but then Diamond Crossing picks up where she left off. She has carted away the charred ruins, and she has fully entered the industrial revolution. She again uses found materials, but from a Pennsylvania freight yard rather than used lumber. She again has a geometric construct out of Minimalism, slightly elevated off the floor by two by fours, while complicating it. And she again suggests the metaphor of bridging or connecting, while cutting off a fuller passage into the light.

Rather than burning her bridges, this time she depends on the gallery's dimensions for her limits, with rails running right to the walls. However, she lays them diagonally, and she doubles them, like a giant tic-tac-toe board or a floating hashtag.  Minimalism asked one to walk on or through the work, while also looking around to find its place and one's own. Here there is no getting beyond the art object, except by leaving. It is beautiful in its simplicity, and the unity it imposes on the gallery belongs both to Vitale and to you. As to where one has seen those tracks before and whether the work in fact demands remembering, that is not half as simple.

Minimalism asked one to walk on or through the work, while also looking around to find its place and one's own. Here there is no getting beyond the art object, except by leaving. It is beautiful in its simplicity, and the unity it imposes on the gallery belongs both to Vitale and to you. As to where one has seen those tracks before and whether the work in fact demands remembering, that is not half as simple.

Kounellis has one remembering, but what? His rail line is short and single, behind a partition at the back. By then, it has already acquired quite a history. One has passed ornate glassware, tons of it, which he means as contrasting in its fragility, although it seems to have survived well enough. One has passed coal, too, its rough glistening in contrast to the matte regularity of floors, shelves, or covering iron sheets right out of Richard Serra. As with his last show, Kounellis also hangs out dark, heavy clothing—on the way to a steel wall, holding still more coal, like America for Greg Lindquist, and broken by crushed sewing machines.

What disasters have these remnants in rails and machinery survived—or, like whoever owned that clothing, has nothing human survived at all? Born in Greece, the Italian artist is again crossing Joseph Beuys and Arte Povera, while muting their lectures. His 2007 show had dry plants emerging from rolled iron as if from abandonment and ruin, and its woolens and old bedding hinted at suffering. Here the rails could once have transported the coal or facilitated the Holocaust. At the same time, the sewing machines remind me of my grandmother's from Brighton Beach, although hers had a pedal rather than cranks. I used it for years as a table.

The High Line promised to preserve a heritage, when others wanted to tear it down. Yet it cuts off the past all the same—by its height, by slick amenities, and by the crowds from out of town who would rather parade its length than look at art. It is a pleasure, at least on quiet days, and it will be more so as it extends north. Still, for now I prefer the Low Line. Vitale and Kounellis have something in common beyond a rail: Minimalism, too, has a deep history, but only if one makes it one's own.

Christian Haub ran at Kathryn Markel through April 13, 2013, Adam Fowler at Margaret Thatcher Projects through May 4, Thornton Willis at Elizabeth Harris through April 13, Thomas Nozkowski's latest at Pace through March 23, Ted Stamm at Marianne Boesky through April 27, Richard Nonas at James Fuentes through April 21, Jim Osman at Lesley Heller through April 14, Marianne Vitale at Zach Feuer through June 15, and Jannis Kounellis at Cheim & Read through June 22. A related review from last year tried to identify a Neo-Minimalism rooted in the post-industrial everyday, and another compared Minimalism old and new. That of course differs from what some people have called Post-Minimalism in the quirkier or more organic forms of Eve Hesse and others in the 1960s and 1970s. Another related review picks up Jim Osman in 2019.