Sunday in the Circus

John Haberin New York City

Georges Seurat: Circus Sideshow

Impressionism: Public Parks, Private Gardens

The painter known for a Sunday in the park spent much of his all too brief career out of the sun. "Seurat's Circus Sideshow" centers on a painting by Georges Seurat. It finds him haunting the fairgrounds and music halls of working-class Paris at night—and haunted by the actors and their audience. As a postscript, the Met returns to his time for La Grande Jatte and other public parks and private gardens.

If you come humming Sunday in the Park with George, be prepared to change your tune. If you come expecting a romantic interest named Dot, you will find neither puns nor a romance to explain the painting away. If you seek people assembling together and airing their lives, you will find only people in shadow, talking among themselves. If you seek the newly triumphant middle class letting its hair down at the beach, you will find instead an unsettling mix of classes unable to separate spectacle from the theater of modern life.  If you seek Impressionist colors, you will find the eerie purples and greens of a fairground at night. If you come looking for Seurat, you may find a history only incidentally his at all.

If you seek Impressionist colors, you will find the eerie purples and greens of a fairground at night. If you come looking for Seurat, you may find a history only incidentally his at all.

It belongs after all to a changing Paris. What starts as the story of a painting becomes a story of the circus and its changing place in society at the turn of the century. What stood at first for a tawdry spectacle became a serious business, with a routine all its own. And what served Seurat as a place to hone his art became the site of an emerging avant-garde. In no time, the spectacle looks tawdrier than ever. Now, though, art's sympathy is with the artifice—and with life on the edge.

Just a sideshow

A sideshow sounds like a distraction from the main event, but the French, la parade, sounds more like a public display. For Georges Seurat, it could be both. Parade de Cirque depicts the Corvi circus, which ran each year at the Gingerbread Fair, before Easter. It had its clowns, tightrope walkers, strong men, fat ladies, and a wheel of fortune. Stereotypical black faces added to the entertainment and embarrassment. Just setting things up and knocking them down were quite a spectacle.

Seurat, though, centers his painting on a solitary trombone player, at one end of a line of musicians and rising above them. He relegates the ringmaster, Ferdinand Corvi, to the right—locked in rigid profile between the verticals of box-office windows, a poster, and his own old-fashioned coattails. Rows of artificial lights command the scene from above, the topmost spreading like flames. They have a counterpoint in the points of light and color in Seurat's Pointillism or Divisionism. Spectators, seen from the rear, appear in near silhouette across the bottom. They become a kind of orchestra pit themselves, and the artist must have stood among them, even as the painting engages the actual musicians head on.

The painting appeared in the very first show at MoMA, and the Met acquired it as a bequest in 1960. Smaller exhibitions have focused similarly on a work from the collection, like recent shows of Jan van Eyck and a portrait of Benjamin Franklin. And this, too, starts as a look at a single work in context—of Seurat's few major paintings, the only one in a New York museum. Preliminary drawings stand across from circus posters and contemporary illustrations. The museum declines to borrow La Grande Jatte from Chicago. This is no walk in the park.

Still, the Met has no end of resources, including a circus orchestra's worth of period instruments. (Adolphe Sax himself designed the saxophone.) It also quickly broadens its focus. Seurat paints free entertainment set outside the circus tent, and his painting serves in its own way as a teaser. The exhibition fills the Robert Lehman wing (which projects into Central Park). It extends to more of his work on paper, contemporaries, followers, and more.

Seurat began the work in 1887, still in his twenties, and found a champion in Félix Fénéon, but he had just four more years to live. He was also working among others outside the official Salon, including artists little known today. Fernand Pelez painted saltimbanques, or itinerant circus performers, that same year. Titled Grimaces and Misery, his life-size canvas unsettled reviewers with its women seemingly on sale, a dwarf, a clown with gaping red lips and head thrown back as if in death, and musicians too tired to raise their instruments. No one pounds the huge drum. The circus would have used it to drum up business, and Pelez had anything in mind but that.

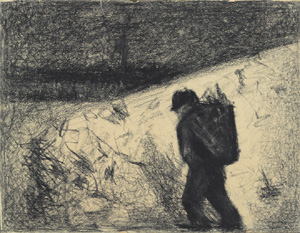

Seurat, too, does not shy away from Paris in all its poverty and spectacle—or from a performer's vulnerability under the viewer's gaze. In the painting, a boy could almost be commanding the ringmaster. And in drawings, striped clowns stand on a platform as if awaiting the gallows. They glow in the demanding precision of a Conté crayon, even as they fade into a blur. An isolated spectator's head comes that much closer to darkness, while a tree embraces a single lamp like a full moon. The artist places the circus between popular entertainment and the shadow of death.

Beyond the music hall

Still, he was never a painter of desolation or a cynic. Honoré Daumier transformed class divisions and political actors into an exaggerated circus as far back as the 1830s. Later Daumier allowed the circus its own shame, twenty years before Pelez. Seurat, in contrast, shows little agony and a great deal of dignity, like clowns who reach out to one another for choreography or comfort. He cannot look down on the performers, no more than to a ragpicker in another drawing, because he is one himself. In the finished painting, the tree remains as a hint of life, but the lunar light has gone.

Other drawings take him to the music halls, a quarter that artists knew as their own. MoMA looked at Seurat drawings in 1008, and they still show a great colorist at his finest in black and white. Musicians and dancers in rising and falling parallels carry the rhythm of performance, much as the slide of the trombonist in the painting seems to rise and fall before one's eyes. Others, too, came to Montmartre in search of nightlife, including Paul Signac, Louis Hayet, and later Pablo Picasso. Seurat shares their interest in color theory, as with the contrasting band of colored dots around a painting's edge—but with a palette that takes it more fully into evening wear and artificial light.

The exhibition fills in other influences as well. It includes a Japanese print, Neoclassicism after J. A. D. Ingres, and a color wheel by Hayet. It also has one of several prints of Jesus before Pilate by Rembrandt, a drypoint from roughly 1655. There, too, a platform presents an actor to the mob and the reality of death, but with the possibility of eternal life. Finally, the show asks what came next in art and nightlife. What begins as Seurat's influence quickly leaves him behind.

The exhibition fills in other influences as well. It includes a Japanese print, Neoclassicism after J. A. D. Ingres, and a color wheel by Hayet. It also has one of several prints of Jesus before Pilate by Rembrandt, a drypoint from roughly 1655. There, too, a platform presents an actor to the mob and the reality of death, but with the possibility of eternal life. Finally, the show asks what came next in art and nightlife. What begins as Seurat's influence quickly leaves him behind.

The curators, the Met's Susan Alyson Stein and Richard Thomson of the University of Edinburgh, go as far as Pablo Picasso, although not the saltimbanques of Picasso's Rose Period. They are after something darker. Louis Anquetin's tracery above a nighttime street looks toward Vincent van Gogh—and Emile Bernard's silhouettes to Picasso in Barcelona. Henri-Gabriel Ibels contributes posters and prints in the style of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Pierre Bonnard presents his clown to the masses, while others add touches of Art Nouveau.

The show closes its circle with Daumier, well before Seurat. It closes, too, somewhere closer to Bob Dylan and "Desolation Row." The circus is in town, and it has got the blind commissioner in a trance. Seurat, though, finds detachment not in caricature, but in color and light. He casts a haze over everything, and then he penetrates the haze. He also finds common ground between transiency and eternity—and between the stage and modern life.

He painted the Eiffel Tower in 1889, the very year it rose above the World's Fair as an emblem of both the spectacle and the city, and his bathers enjoy the suburbs, even as smoke from a factory rises in the distance. He painted models in his studio with his Grand Jatte in place of a picture window onto nature and society. (The show borrows a smaller version of the painting, not the one in the Barnes Foundation.) He gives one model a more relaxed and stable pose than in a preliminary drawing as well. There, as at the circus, he makes the performer a collaborator. And then he gives his brush or crayon a life of its own.

En plein where?

The Impressionist circle struggled together and squabbled, but it could always agree on one thing: paint en plein air, outdoors in natural light, and paint what you see. Where, though, was that, and what did they see? For the Met, en plein air in France meant two places, and "Public Parks, Private Gardens" sees them both as recent creations. It allows a fresh look at the collection, downstairs in the Lehman wing rather than half hidden behind Auguste Rodin and academic painting—much as Impressionism offered a fresh look at color, light, and art. It also offers a history of parks and gardens from, as the show's subtitle has it, Paris to Provence.

You may find yourself marveling at what, all along, lay right before your eyes. You knew that Seurat, so reticent, nonetheless depicted the public spectacle of La Grande Jatte, for Sunday in the park with Georges. You knew how Claude Monet spent the day up the Seine at Argenteuil with Pierre-Auguste Renoir—and ended his days in the luxuriant privacy of water lilies and Giverny. What, though, changed along the way? The curators, Susan Alyson Stein with Colta Ive and Laura D. Corey, start with grand boulevards and estates under Louis XIV, but then a rebellion against them in the name of natural beauty and public access. Parks took shape as part of the remaking of Paris by Baron Haussmann under Louis Napoleon.

The rebellion demanded attention to native and exotic species. It drew on the English picturesque movement, as a relief from industrial England, much like Thomas Cole in America. It also had the encouragement of Napoleon I and Josephine, who built a pavilion for her interest in botany. (For all the display of gardening tools, this is a decidedly top-down history, of emperors rather than scientists.) Those startling sunflowers by Vincent van Gogh appear against a background of botanical studies and a revival of still life, starting with Eugène Delacroix and Romanticism. Edouard Manet had his peonies and the fruit beside his Woman in a Striped Dress, Renoir his chrysanthemums, Monet his irises, Mary Cassatt her lilacs, and Henri Matisse, too, his lilies.

The changes drew Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau to Fontainebleau, for the turmoil of vegetation with seemingly nowhere to stand. They drew Monet to the wildly curving alleys of Parc Monceau, Renoir to Versailles for his freest oil washes, photographers like Charles Marville to the Bois de Boulogne and Eugène Atget to the Luxembourg gardens, and Camille Pissarro to the Tuileries under changing seasons. As for the private gardens, they arose along with a leisure class that soon included painters. Honoré Daumier had no trouble mocking it. ("I thought it would be more fun than this," a petit bourgeois exclaims while watering the plants.) Yet he, too, found peace in a man outdoors reading.

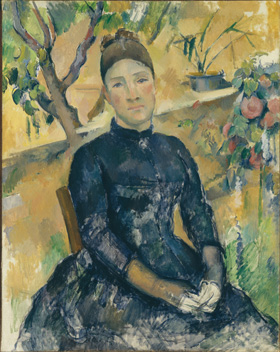

Paul Cézanne, Edouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, Corot, and Monet all had the benefit of family property, Félix Vallotton his wife's family money. Gustave Caillebotte was a gardener, and Monet created Giverny as both privileged enclave and a subject for paint. The sense of an idyll also goes into the genre of portraits in the garden. Monet, Edouard Manet, and Paul Cézanne painted their wives. While the identification of woman and nature sounds suspect, Cassatt and Berthe Morisot adopted it as well. And then Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec played against it, with a streetwalker in Montmartre.

The Met has the advantage of depth, from a portrait of Monet at work beside his family, by Manet, to film of him at his easel in Giverny. It also has the advantage of familiarity. Monet's terrace at Le Havre or an older woman sharing her elegance with a floral arrangement, by Edgar Degas, will be on anyone's list of greatest hits. The museum has the disadvantage of recalling its intrusions into Central Park, worst of all with the Lehman wing. Still, that should have one thinking about the park as another very public and human creation. The twin legacy of real-estate deals and the Romantic garden continues to this day, in plain view.

"Seurat's Circus Sideshow" ran at the Met through May 29, 2017, and "Public Parks, Private Gardens" through July 29, 2018. A related review looks at Seurat's drawings.