Tolerating Politics

John Haberin New York City

Zero Tolerance and Crossing Brooklyn

What if political art is a waste of time? What if it cannot overcome the tension between politics and art?

Painters and sculptors ask that all the time, but they may not have quite the right grievance. No, not what if it wastes talents that could be making "real" art. What if it wastes the imperative that should be political? The twenty artists and collectives in "Zero Tolerance" cannot get enough of street protests—to the point of ransacking YouTube for it, recreating it, or just plain making it up. Yet they end up making art and protest alike look futile. Shared hopes for the future start to look all too much like a thing of the past.

Political art can underscore the urgency of both politics and art, by pointing to their common ground. At its best, as the saying goes, the personal is the political. For MoMA PS1's director, though, that is just not good enough. As curator with Mia Locks and Margaret Aldredge, Klaus Biesenbach wants to cut right to the action. "Zero Tolerance" compiles photos and footage of protests in every one of the world's hot spots, grouped geographically. The show's title, after the policy of strict policing in New York under the "broken windows" theory, poses right off an opposition between order and freedom. Like the even glibber dedication to art as community at the Brooklyn Museum as "Crossing Brooklyn," it could do with a lot more art and a lot less tolerance.

The future of protest

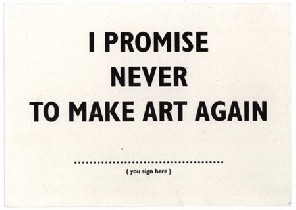

"Zero Tolerance" shares PS1 with a tent for kids to make art and an upbeat message: Art Makes People Powerful. Yet that message itself shares space with dumpsters asking one to turn in one's art. Bob and Roberta Smith offer a choice of statements to sign in the process—a promise never to make art again, a wish only never to see this art again, or a pledge to enable others to "be all they can be" by choosing art school. Are the Smiths, a pseudonym for Patrick Brill, even aware of the contradictions? What about the contradiction in trashing art as a performance piece that has now lasted well over a decade?

One could put the British artist's failure to abandon art down to a lack of discipline, but much of "Zero Tolerance" revels in just that. Protest for Halil Altindere targets Istanbul's urban renewal but amounts to youth letting it all hang out. Asco, a Chicano street collective, takes much the same view of LA. Art here looks most self-indulgent at its most personal, too, because that is when the stars come out. John and Yoko are back at the center of their media circus to "give peace a chance," while Joseph Beuys and Peter Weibel put in quick appearances for some half-forgotten cause looking themselves like rock stars. Pussy Riot hogs close-ups in a cathedral, less to locate a community of ordinary Russians than to take on the aura of the church and of ritual.

Effective protest necessarily extends beyond the personal, but then artists who celebrate it have a way of leveling the issues along with the actors. Rirkrit Tiravanija carries his populism to commissioning Demonstration Drawings from volunteers. Ahmed Basiony's raw footage of the Arab spring looks just as impersonal, especially paired with footage of himself in a high-tech sweat suit of his own devising, perhaps to show that artists can sweat the big stuff. Harun Farocki more lovingly compiles documentary records of Romanian uprisings, while Igor Grubic sticks to gay pride in Croatia, but one needs a wall label to tell them apart from one another—or sheer anarchy. Artur Zmijewski can point to genuine heroes in Palestine, Warsaw, and Belfast, as he did with Hans Haacke in 2010, albeit on monitors hung at random. He would earn the title Democracies more, though, if he did not count football rallies as politics.

Others get around the limits of the documentary by staging their own rallies. Lorraine O'Grady joins the African American Day parade, picture frames in hand, to photograph fellow marchers. It turns individual aspirations and community alike into black performance art. When Oyvind Fahlström marches for hope, he means Bob Hope, but should one be laughing or crying? Mircea Cantor marches in Albania with reflective surfaces as the sole banners. Maybe the best political art should be your mirror, but then can it still be political?

Still others look for ways of individualizing protest in the face of overwhelming authority. Amal Kenawy, who contributed to art of the Arab world at the New Museum, leads human "sheep" through Cairo, while Song Dong breathes in the dust of Tienanmen Square. Deborah Kelly so cherishes the image there of a man facing down tanks that she tries to improve it, with artful design. Zhao Zhao takes empathy to the point of posting guard there on behalf of the regime. Christoph Schlingensief is back at the museum after a matter of weeks to offer political asylum in the form of shipping containers. They look colorful, if not comforting.

Maybe protest looks vain simply because of the moment, as at the 2015 New Museum Triennial, especially amid protests directed at Klaus Biesenbach himself to step down. Hopes for the Arab spring and Tienanmen Square have already faded brutally into memory, while Occupy Wall Street carried an ambiguous message—to abstain from partisan politics or to seize the day. War Is Over If You Want It from John and Yoko sounds painfully naive, although Bettina WitteVeen has since made the same message brutally honest. Sharon Hayes sets her witty "simulated protests" in "the near future," but they dwell on anti-Communist witch hunts and Vietnam. "When," a placard cries out, "is this going to end?" Indeed. A little self-righteousness in art can go a long way, but can it still look ahead?

Double-Crossing Brooklyn

The Brooklyn Museum wants to do right by Brooklyn. It wants to reach out to its community, from artists and students to a budding public for art. And it wants to reach out to their concerns, for their neighborhoods, their identities, their politics, and the planet. One can see those twin aims in everything from the deadly 2010 renovation to extended hours and curatorial changes—and from the permanent display of Judy Chicago to socially aware exhibitions of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lorna Simpson, the Great Migration, the Civil Rights movement, Wangechi Mutu, women in Pop Art, "Global Feminisms," gay artists, "queering nature, SWOON, Mickalene Thomas, El Anatsui, and Ai Weiwei. But could those aims come into conflict? Apparently so, and "Crossing Brooklyn" comes down squarely on the side of the second, at the expense of either serious politics or art.

Truth be told, the museum's changes and programs have looked far more often tawdry and tired than enlightening. And here the thirty-five Brooklyn artists and collectives settle for a lame rehash of that touchy-feely mix of performance and installations known as relational esthetics. The curators, Eugenie Tsai and Rujeko Hockley, adopt the subtitle "Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, and Beyond," but it could not look less like Bushwick's galleries and open studios had they turned instead to Jeffrey Deitch and Larry Gagosian. Now, that could be a good thing. What if it unsettled one's expectations about the endless search for bankable emerging artists, collectibles, and the next big thing? In practice, though, the work could not be more predictable.

Truth be told, the museum's changes and programs have looked far more often tawdry and tired than enlightening. And here the thirty-five Brooklyn artists and collectives settle for a lame rehash of that touchy-feely mix of performance and installations known as relational esthetics. The curators, Eugenie Tsai and Rujeko Hockley, adopt the subtitle "Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, and Beyond," but it could not look less like Bushwick's galleries and open studios had they turned instead to Jeffrey Deitch and Larry Gagosian. Now, that could be a good thing. What if it unsettled one's expectations about the endless search for bankable emerging artists, collectibles, and the next big thing? In practice, though, the work could not be more predictable.

It does not just repeat past trends. (Frankly, if a proper follower of Rirkrit Tiravanija had turned up to dole out free curry, I might have welcomed it, since I was hungry.) It also repeats the same tricks and tropes to the point that one blends into another. Forgive me if this once I omit names, to mitigate the blame and to reflect the sameness. Regular readers of this site will recognize William Lamson and his concern for process, Janine Antoni and her feminism, Cynthia Daignault and her knowing wink at painting and its viewers, and Steffani Jemison and Mary Mattingly and their fears for climate change and the earth. They have all seen better days apart from the crowd.

Virtue, alas, is abundantly rewarded. Artists photograph borough residents looking as proud as selfies, and they transfer the borough's portraits onto plastic bags and smileys. They track down classical dance in the museum and taxi dancers in Queens. They "interpret" the speeches of Huey Newton in black and start their own lecture center. They solicit your thoughts about nothing in particular and your contributions pinned to a statue from ancient Rome. They bring you, in letters, their love.

At some point, the sameness alone may make you gag, if not also the sentiment. They remember their grandmother's recipes and, like Hollis Sigler, their grandmother's samplers. They build sheds in the gallery for a woman aging gracefully and for carrier pigeons to Cuba. They do indeed serve up food, from the ices of Latino street vendors to the products of a community garden. They reconstruct their street corners with still another model, with photographs of chain-link fencing, and in walk after walk after walk. They roam Brooklyn at night and the New Jersey Meadowlands and Brazil by day, row the city's waterways and drift standing up on the Delaware, accompany the borough's clouds with Motown hits and sketch them each day for a friend in prison, haul its garbage down the sidewalk and collect its scraps for posterity.

Many Brooklyn artists feel excluded from the art world, and some resent this show for its near exclusion of painting and sculpture. Ken Johnson in The Times sure did, but then he judges every show by whether it has enough expressive brushwork. They are wrong, and not just because one should never judge a show because one has another in mind. For all they know, this could become just the first in a series of shows about Brooklyn—along with a welcome reminder that so much rides on the fate of midlevel galleries, between high-end galleries and DIY. Its lesson is not that painting is lacking or political art is bad. It is that virtue alone cannot do right by Brooklyn or by art.

"Zero Tolerance" ran at MoMA PS1 through April 13, 2015, and Bob and Roberta Smith through March 8, "Crossing Brooklyn: Bushwick, Bed-Stuy, and Beyond" at The Brooklyn Museum through January 4.