Questioning Money

John Haberin New York City

Art and Influence: A Student's Questions

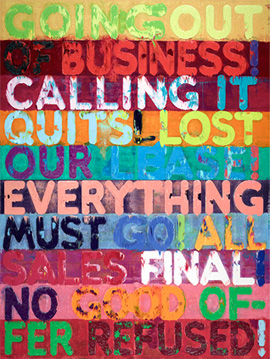

As I write, on Black Friday, has every day in art become an overhyped sale? Or, as a student, Lee Sally, wrote me, do you believe that the increasingly money driven art world—which led to the rise of investors, administrators, and art dealers—deteriorates the true substance of art? Short answer: yes, absolutely.

Long answer: yes, but it sure is complicated, and you have to find your own answer. If you are an aspiring artist, dealer, or critic, you can even help create the answers in a messy, disturbing, but still pretty exciting art scene. My opening question came to me in November 2015 from someone still excited, and I wanted to encourage her and others to do just that.

Black Friday

First, though, she had a second question: does this ever make you question the validity of art critiques? It can, and even decent arts writers get caught up in the game. If you think that you have seen a constant flow of puff pieces in respectable magazines and newspapers, you have. I am a big supporter of "theory" as a way of asking questions and opening people's eyes, mine included. I have encouraged people to complain not about artspeak, especially long after so many formidable critics and theorists from Jacques Derrida to Arthur C. Danto have passed away, but rather martspeak.

And yet the answer to the second question should be a firm no. I could even say that the upside of complaining about money is that it gives me something to write about, just as for Sarah Meyohas it give the data for her art. It could actually make talking about it and writing about it more important. I have returned often to the horrendous financial pressures from art fairs, art advisors, fall openings, real estate, private collectors, museum expansions, museum destruction, auction prices, and more. I have singled out artists trying to navigate these pressures and dealers asking whether galleries still matter. I have engaged often with critics like Jerry Saltz, Peter Schjeldahl, Edward Winkleman, and Ben Davis out to do the same.

In other words, the real long answer is "don't get me started." Can one even speak of a "true substance" to art, so long after great modern and postmodern artists worked to dismantle just that? Besides, rather than offering my own pat answers, I wanted to pose my own questions, as a teacher. With luck, the student and others to come will be putting me out of business. Ready? Here is what else I wrote:

- Many worry, as I have elsewhere, that astronomical auction prices, celebrity artists, the emphasis on blockbuster museum shows, and the like are ruining art. Is that valid, or is that mistaking the 1 percent for everyone else?

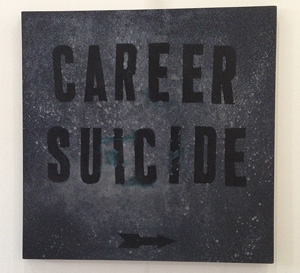

- Many sincere artists who are not succeeding feel that all this attention stacks the deck against them, at the cost of cynicism about art. How many are just making excuses for tepid, derivative art?

- There is a whole other side of money—not just big bucks for the few, but the amazing growth in numbers of artists, exhibitions, and dealers, plus a much greater audience for them all. People crowd museums and gallery openings, as would have been unthinkable not so very long ago. Is that good for art and a genuine democratization, or does it commercialize everything, too?

- If it makes art too much like the movies, does that mean that there can never be great movies? Does it mean that there is something special about art? Just what? Would many excellent artists from Dada and Pop Art to the "Pictures generation" and today disagree?

- Can even big money dealers contribute something, with exhibitions that no one else can afford to stage?

- Is there an altogether more important downside, in the costs to ordinary art dealers even before being reduced to "virtual exhibitions" and cautious reopenings after Covid-19—in rents, attendance at art fairs, competition for buyers, difficulty getting the publicity they deserve, you name it? Or when is competition a good thing?

- Does all this mean that there is a new and stifling norm, or rather is the problem that now anything goes, so there never can be a truly innovative new direction?

I wonder, every day.

One person's answer

Did I say I wonder about big money in art? So, it turns out, does the reader I mentioned—and then some. Is the art world just Black Friday year round? When I replied to her questions with questions, I meant only to help others think through the problem for themselves. I never dreamed of piling yet another assignment on an overworked student, but she dug right in, often with thoughts very different from mine. With no further editorializing, then, and modest editing, let me turn over the page over to Lee, with no further effort to make her speak for me.

- The 1 percent and everyone else

"In the real world, the 1 percent largely drives the economy, and that includes the art world. Although it could be a gesture of marginalization, ignoring the many artists and galleries out there that much more, taking the 1 percent for everyone else might be not a mistake at all—at least not all the time. Make that at least not 50 percent of the time, because 50 percent of the world's wealth currently belongs to the 1 percent.

"Things are constructed around what sells, because it is only human to desire a better standard of living. And works are more likely to sell if they have a certain shock value rather than an idea manifested after long sessions spent understanding the context. Or maybe shock is just the route that fine art is taking because there are already enough nice things to look at, and it wants to be novel. Either way, what sells is often what is advertised well to an audience with increasingly shorter attention spans.

"Things are constructed around what sells, because it is only human to desire a better standard of living. And works are more likely to sell if they have a certain shock value rather than an idea manifested after long sessions spent understanding the context. Or maybe shock is just the route that fine art is taking because there are already enough nice things to look at, and it wants to be novel. Either way, what sells is often what is advertised well to an audience with increasingly shorter attention spans.

"Yes, time is another factor driving deterioration in art. More emphasis is placed on overnight sensations, because that kind of celebrity comes quickly and easily. Amid the information overdose, people prefer already validated things and opinions. It is just hard to keep track of the many opinions vocalized, liked, and tweeted, so art is becoming crazier along with the world.

"Now, this could be just my opinion, too, on top of so many others. I prefer art in touch with a tangible value system because it gives me the feeling that I am not lost. That makes me believe that art was better overall before Postmodernism, deconstruction, and 'the anti-aesthetic' than today."

- Stacking the deck

"My straight answer would be that artists who think the deck is stacked against them are making excuses, but understandably. Of course, excuses have negative connotations—self-serving, wimpy, and reluctant to confront reality. I just mean that here they are the consequences of fervid expectations.

"We all like to believe that what we are doing is right and worthy. Even criminals might say they are victims of a corrupt society or just trying to make ends meet. Emerging or struggling artists want to blame something, anything, other than themselves—and why not? After all, their ego and self-worth are already hurt from being unsuccessful. Besides, what is success? A valuable and fulfilling life should not revolve around money."

- New money and new audiences

"Yes, art should be more accessible to more people, and art with greater press coverage interests a greater audience. But big arts institutions are not necessarily more inclusionary. I criticize sky-rocketing price tags because they exclude much of the public. The money generated from art should be invested not in earning even more money, but in artists, students, education, and social welfare."

- Movies, art, and elitism

"In capitalism, democratization is inseparable from commercialization, so it is hard to argue for one and against the other. Even coming out of Hollywood, great movies open eyes, and studios that sincerely think a movie will be bad will cut production. And yet commercialization is still a danger, even for movies, and art and movies are still different endeavors. More than with movies, art is subject to divergent perspectives and to elitism. Even if the general public hates Made in Heaven by Jeff Koons or A Thousand Years by Damien Hirst, they still sell for millions. Pop Art after Andy Warhol reveled in this special quality of the art world because it kept money flowing."

- Big dealers as a big deal

"Big money dealers contribute something, too, but they are in it for themselves as well. They would not do something if there was not a profit in it. I cannot go along with the many people who acclaim then as heroes, because heroism is not reserved for people with money."

- The rest of us

"Competition has its benefits, but not only benefits. The pressure to be Number One can in fact restrict creative freedom. Too often, people copy things that were already successful, fearing failure and rejection. The positive side of competition could be extracted equally if not more so from inspirational people and events, because they motivate others to work hard, to work creatively, and to explore ideas."

- A new norm?

"People create imperfect institutions, because people are imperfect mortals. This is not an ideal world, but we all strive for a better tomorrow. We can achieve it, however, only if teachers, parents, and leaders realize that our lives are ephemeral—and wasted without love."

And do not forget the 2016 art fairs coming up.