A State of Emergency

John Haberin New York City

Nari Ward, Sterling Ruby, Brian Conley, and David Maisel

On the fading days of winter, art in 2010 seemed in a state of emergency. Nari Ward even brought an ambulance into a Chelsea gallery. He was reflecting on the toll of racism and the police department's wall of silence on ghetto youth. He could have been speaking of art itself in the recession.

Death and incarceration have hung over show after show, in each case haunted by the temptation of violence and easy pleasures. Sterling Ruby combines a cattle car for prisoners with a rock band's tour bus. Brian Conley restages death in Iraq as a war game in Brooklyn. And David Maisel photographs the decay of decay itself—with cans holding the ashes of institutionalized mental patients. Here, too, the oppressive institution could be art, but it tells moving and seductive lies.

White car crash

If art is looking more and more like an extended car wreck, at least Nari Ward has the sense to call an ambulance. He also brings empathy for its inner-city victims and, he implies, their invisibility. An ambulance takes over the room, with nothing behind its windows but smoke. Here even a white vehicle contains blackness. (Elsewhere, in a Whitney Biennial and in "Grief and Grievance," Nari Ward has called a hearse.)

Nari Ward often sees things in black and white. He piles up telescopes and their tripods, like discarded walkers for the elderly or injured. He slices church pews down the middle to look like wheelchairs with no place to sit. He turns an upside-down chandelier into votive candles with cotton flames, perhaps for the rags hanging down from above. He sews more cotton or cloth onto Medicine Balls, like basketballs or bowling balls transformed into a pile of sculls. All come stained in ink or painted black.

In all this a crash has taken place, part of a crash course in urban sociology. Ward makes even race a mystery, in x-rays of a human skull littered with small black marks, from shoe laces but like curly hair. He also makes it both up front and invisible, at least to white eyes. He can descend to hectoring, with a giant black debit card, but there, too, he points to absence and exclusion. He has braided its card holder out of, I am guessing, cowrie shells—but illegibly. And then there is Sick Smoke, the centerpiece and the emergency.

The motif goes back at least to John Chamberlain, who sometimes denied the association, and Andy Warhol, with his Green Car Crash. In an era of big money, trashy gestures, bad boys, and dead celebrities like Andy Warhol himself, it has become all too frequent, even apart from Cai Guo-Qiang on a museum scale—or John Bock in the New Museum cafeteria for "Skin Fruit." In a single day in Chelsea, one could see that ominous black bus from Sterling Ruby, a maze of trailers from Mike Nelson, and (don't even ask) a DeLorean at the art fairs. The Bruce High Quality Foundation has still another white ambulance, in the misbegotten form of a Cadillac hearse, at the 2010 Whitney Biennial. When I last saw a spectacle of fire and water from Bill Viola, I had to notice how well it fit with the car wash still out there on Tenth Avenue. Now they can help art clean up its act.

Ward plays by the trendy, masculine rules. He has had conceptual art at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and I hardly noticed it. His burnt oil drums at the 2006 Biennial pushed political art toward a tanning salon by Banks Violette. On a first visit, I found his solo show spooky, provocative, scattered, and a mess. A second or third time, though, I paid less attention to the ambulance and more to its surroundings. While the ambulance already points to shared themes, I could feel the visual unity and urgency even more once I mentally set it aside.

With it, he plays the bad boy, but he has a documentary side, too, about boys pressured to behave badly or well. A video, Fathers and Sons, interviews black police officers who must deal with even younger African Americans. I headed out for deeper memories and darker explosions two blocks away—large paintings by Gary Simmons. I thought, too, of jazzier and funnier mixed media in black by Rashid Johnson. Ward is more of a showman and moralist, as one would expect for video shot at Al Sharpton's Action Network House. He is also confronting head-on the impulses toward showmanship and responsibility.

The boys on the bus

A black bus faces off against a cage on the same scale, like a cattle car. The press release calls "2TRAPS" a critique of reason. None too reasonably, it cites Max Weber's great sociology of religion as a model. Yet emotion for Sterling Ruby looks anything but liberating. As he wrote on a previous work (in full capitals), "The past has cheated me . . . / the present torments me . . . / the future terrifies me!"

Reviews of Bronzino drawings at the Met often single out the Florentine master's relevance today. And the parallels between his time and Postmodernism are startling, as Jerry Saltz and Peter Schjeldahl note in speaking of a Neo-Mannerism. "Instead of the late Renaissance or the antithesis of the Renaissance," I wrote back in 2003, "one might well call Mannerism the Post-Renaissance." They had it all—riffs on art's last grand narrative, a transition to art's future that never seems to come, religious wars, and an uncertain state of empire. For artists like Pontormo and Parmigianino, art held anxiety and sexuality, nostalgia and fierce rebellion, glossy surfaces and crumbling forms, instability and identity, politics and private obsessions. If rationality and technology today equate to Modernism, they once meant High Renaissance symmetry and linear perspective.

Ruby is in the running for today's leading mannerist. His dark ceramic loops on white pedestals, at Metro Pictures in 2008, sure looked mannered enough. Franz West might have left them as droppings on the studio floor. If their gnarled surfaces reflect literally a hand job, his next New York show supplied some on video. In "The Masturbators," late last fall at Foxy Production, naked porn actors did their duty on bare sets. For Ruby even transport, physical or ecstatic, means confinement.

Ruby is in the running for today's leading mannerist. His dark ceramic loops on white pedestals, at Metro Pictures in 2008, sure looked mannered enough. Franz West might have left them as droppings on the studio floor. If their gnarled surfaces reflect literally a hand job, his next New York show supplied some on video. In "The Masturbators," late last fall at Foxy Production, naked porn actors did their duty on bare sets. For Ruby even transport, physical or ecstatic, means confinement.

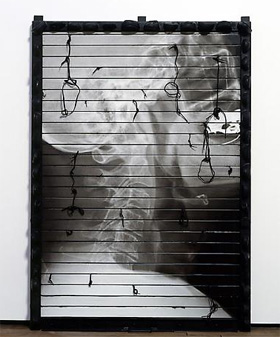

The "stalagmites" reappeared at LA MOCA as a further image of entrapment. "SUPERMAX 2008," which I did not see, claimed to map the Pacific Design Center onto a maximum security prison. And now this. Pig Pen consists of security gates, like ghetto storefronts at night, but a good four layers deep. More gates confine the black vinyl seating on Bus, which in fact transported convicts before serving a rock band as a tour bus—named, of course, Extreme. I take this history from lettering across the bus and on faith, although the garish orange lettering is hardly legible and faith is in short supply.

Roberta Smith ranks Ruby high on her list of "bad boys." He clearly shares an obsession with bright lights, big gestures, surveillance, sex, and death. With black spray paint, florescent tubes, and the bus's display of loudspeaker cones and their chrome housing, he even matches the color scheme of Banks Violette, as in his memorial to Dash Snow. Black is the new black. Like Alan Vega and the bad boys, too, he can be thoroughly glib and piercingly clever at the same time. In its title alone, Pig Pen puns on filth, police, and prison, and it wallows in whatever it can.

However, Ruby lacks the cheerful pandering of Jeff Koons or the confident moralizing of Damien Hirst. He does not have the detached smirk of Paul McCarthy, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, or Mike Kelley and Michael Smith. He is too deep in abjection. A short stoop almost admits one into Pig Pen, where the zigzag of gated panels could indeed invoke Modernism, like Broadway Boogie-Woogie for Piet Mondrian but way, way off-Broadway. I found Ruby's past work, including "The Masturbators," just plain boring and the new work obvious. But it challenged me and invited me in, just as it must have repelled and tempted the artist before me.

Rules of engagement

By "How Not to Depict a War," a Times reporter did not mean a tabletop in Brooklyn. But what would he have thought of Brian Conley? War, he might have said, is not a game. And Conley would agree.

With the Oscars coming up, Michael Kamber finally got around to watching The Hurt Locker. Filmed near the Iraqi border, with Iraqi refugees as extras, it made combat raw, immediate, and anything but welcoming. For all its acclaim, though, Kamber saw only fantasy heroics, and he is not the first. Where actors take chances alone, he insisted, real soldiers depend on the company of others. Where film characters beat death by their skill in a firefight, real casualties tend to come from IEDs, remotely detonated. There are rules of engagement, but life and death are a throw of the dice.

You know, it sounds eerily like gaming after all. Conley first staged his miniature desert war in March 2007, appropriately enough in Vegas. Following his directions, others covered a surface with sand, roads, and toy soldiers based on a village near Baghdad, all carefully constructed from such spare parts as Dixie cups and straws. At Boiler@Pierogi, where it fills the room, the sheer emptiness looks convincing. It takes a moment for the implausibly small cluster of buildings to register. They have Spanish-style roofing, and the tower has more in common with a toy lighthouse than a call to prayer.

Death greets one on the way in, and it, too, seems plausible. Photographs appear to show men torn apart at the very moment of an explosion. In reality, the garish color and distorted faces arise from another kind of blowing up. They push low-resolution images of thumbnail-sized toys past the breaking point. For Brooklyn, Conley held an afternoon of gaming, supposedly based on events in Afghanistan. A sack hanging overhead, from which someone did indeed throw dice and direct the proceedings one Saturday, looks creepy enough by itself.

Miniature War in Iraq . . . and Now Afghanistan plays on the appeal of war and gaming. Come to think of it, The Hurt Locker tries to convey the addictive thrills of violence. Lack of realism has a point after all. So do Conley's links to conceptual art and appropriation, which make visiting a guilty if minor pleasure. They also made me think of how hard it is for art to deal with events. At one point even to mention post-9/11 patriotism got Amy Wilson in trouble, then for a while images of disaster were everywhere, and now political art has mostly moved on to the Recession.

Of course, the public mostly has, too, Oscar awards or not. Artists are just like other people and reflect a broader culture, which is in part why the culture truly needs them. Besides, the other desert war in town already approaches a complacent patriotism. Steve Mumford's sappy realism includes earnest GIs, a naked woman, and young Iraqis filled with religious fervor. In case one missed their deep feelings, or in case the art seemed too old-fashioned, Mumford adds text on thick frames out of Neil Jenney, separated by more text on pretend medals and memorials to the dead. One might never know that all this did not begin as a religious war—unless one counts Neoconservatism as a religion.

A can full of dust

Photography is a record of the past and a document of change in the present. Like most truisms, it sounds logical enough, if a little pretentious. After all, one follows from the other. We linger over a photograph album to find out who we were.

Two exhibitions take change as their subject, but not with vintage prints. Rather, they photograph change or subject photographs to change—in effect staging the change themselves. They thus illustrate another truism, that photographs can lie. How, then, can they document anything? Not without sentimentalizing it perhaps, and they do just that. However, the layering of changes, intentional and otherwise, is interesting all by itself.

David Maisel starts with an institution that has itself changed. Oregon State Hospital began as the Oregon State Insane Asylum in 1883, and you need not have read Michel Foucault to associate a madhouse with confinement, control, and chaos. "Library of Dust" displays copper containers, with the ashes of patients interred in the 1970s. (Jack Nicholson in not among them.) They evoke not so much fears of death, unclaimed by love ones, as a fascination with decay. Ironically, sealed containers designed to slow the transition from ashes to ashes must themselves oxidize—as, for that matter, do photos.

They do so colorfully, from electric blues to an almost antique finish. Sometimes the peeling hospital label remains, like something out of a museum of natural history. The grain of the large C prints heightens the process. It also makes them eerily close to silkscreens—in particular, to Andy Warhol, as seen elsewhere in a Warhol retrospective. Is it poignant or manipulative to compare their anonymity to that of soup cans? Maybe both, and it leaves a startling impression.

In "The New Old," the color fades, and the manipulation is more overt. Here, too, the subjects, seen or unseen, are anonymous. And they, too, inhabit a kind of decay, in inner cities. Yorgo Alexopoulos photographed portions of LA in the 1980s, when it resembled the downtown Beirut of Simone Fattal. Stephen Gill started with already dreary fragments of east London, buried them, dug them up, and exhibits the wear and tear. Burton Machen replastered found posters, then returned to shoot the further indignities they have suffered.

They bring photography closer to conceptual art. For Alexopoulos, their loose distribution across the wall even identifies the gallery with an urban underpass. They all dramatize poverty in the banality of neighborhoods that have suffered from gentrification. Then again, Downtown Beirut gave its name to a rock band. Still, of the three only Machen connects visual appeal to layers of time. When a poster of a woman acquires first black-and-white grain and then red graffiti, I could imagine lipstick or a lover turned out on the street hungry for her glamour—like Ward, Ruby, and other artists after all.

Nari Ward ran at Lehmann Maupin, through April 24, 2010, Gary Simmons at Metro Pictures through March 20, Sterling Ruby at Pace in its second Chelsea space through March 20, Brian Conley at The Boiler at Pierogi through March 21, Steve Mumford at Postmasters through March 27, David Maisel at Von Lintel through February 27, and "The New Old" at Invisible-Exports through February 21. Michael Kamber of The New York Times was posting on the newspaper's blog. Related reviews look at Brian Conley in 2018 and Nari Ward in retrospective.