Speaking of Blackness

John Haberin New York City

Ebony, Jet, and Contemporary Art

Material Histories and Eric Wesley

Who knew that African American artists care so much about appearances? "Speaking of People: Ebony, Jet, and Contemporary Art" may have one expecting a wry or subversive look at how magazines shape both people and appearances. It asks instead for the black community to claim both as its own.

Have they subordinated politics and art to commerce? Often yes, but the Studio Museum in Harlem has a solid track record of looking beyond appearances. That can mean, as here, looking past anger to continuity in African American art and black-owned businesses. It can precede a show like this about appearances to one devoted to "Material Histories," in which the museum's artists in residence pile on what remains of hard materials and hard facts. It has also allowed Eric Wesley to display a stubborn resistance. In Chelsea, Wesley utterly refuses to make progress—and a good thing, too.

Culture and community

Skeptical? At the Studio Museum, sixteen top-flight contemporary artists take Ebony and Jet "as a resource and as inspiration." They also offer hardly a trace of criticism, much as the magazines, a popular news monthly and a style weekly, seek an upbeat perspective. In articles and advertising alike, they see a field for their own imaginings. And in Johnson Publishing Company, they see a shining presence in the Chicago skies. With both, they seem to say, this is what a black community looks like.

It may also look like a work in progress, understandably so. Hank Willis Thomas lines an entire room with Jet magazine's "Beauty of the Week," with nothing in common but fashion and change. The black-owned publisher launched the publications in 1945 and 1951, and that is a lot of weeks. Yet for all the treacherous allure of the male gaze and the female body, Thomas brings little more irony than Mickalene Thomas with her own glamour project. Lorna Simpson hints more strongly at cheap thrills in calling her collages Riunite & Ice (that's nice!), but she, too, embeds a proud personal and racial narrative in clothing and hair. As a voice intones for Theaster Gates, "My complexion is political."

In the real world, popular magazines are consumed with stereotypes and surfaces—and impose them. Does that make Ebony and Jet an extension of white America? When Glenn Ligon pairs hair cream and sculpture by Constantin Brancusi, he targets an association of black manhood with "the primitive." As Jeremy Okai Davis puts it with another ad for hair cream, Makes the Man. Still, they have left behind the anger and glee at received images of Pop Art and the "Pictures generation," in search of something more direct and affirming. As curator, Lauren Haynes does after all call the show not "Speaking of Images," but "Speaking of People."

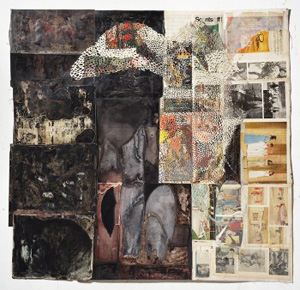

So where are the people? Far more often, this art speaks of commodity and community. Noel Anderson describes his combine as a "sociogram," while Lyle Ashton Harris holds out a t-shirt. Godfried Donkor overlays a magazine page with an entire history of blackness, from slave ships to boxing. And Ayanah Moor like Carol Szymanski treats even dating advice as sociocultural analysis, with much the same amused detachment that skeptics may bring to horoscopes. Her paintings quote hot tips and broad generalizations concerning the women of different cities.

Does all this good cheer mean too many surfaces? Absolutely, but still the artists are acting and looking. Purvis Young and Ellen Gallagher take magazine pages as canvases for their own gestures, Gallagher with her images of repeated eyes. The corporation can itself look both spooky and alluring, in an office carpet for David Hartt or the building's late modern exterior for Martine Syms. When Leslie Hewitt strews flowers and white powder across a metal sheet, the museum becomes a corporate space as well. Could there be a more dangerous and confining notion of community?

Upstairs Titus Kaphar represents one. Kaphar, who sought role models in a show at the Studio Museum of "Midnight's Daydream," now tries to locate his father—or at least his prison records and his name. "The Jerome Project," curated by Naima J. Keith, turned up dozens of men with that name who have been arrested, and paintings render their mug shots in academic realism against gold leaf. The artist then dips the shield-shaped panels in tar that may suppress anything from their chins to their eyes. He means to evoke the aura of medieval icons and the brute force of the "prison-industrial complex," and he could just as well have added the plainness of ancient Roman portraiture. He may end up with only the banality of a magazine spread, and yet he, too, is looking at received imagery and speaking of blackness.

Emerging as material

Of the three artists in "Material Histories," one has words as her materials, while another soaks, stains, and coats his materials to the point of burying their history. The third piles her materials on plainly enough, as if rescuing them from their past. But then art is like that, they might argue, where ideas and things can take on new lives and new histories. And African American art is like that, with the added burden of recovering lives and a history. Piling on materials is also the nature of way too much trashy art and way too many oversized installations. Still, the year's artists in residence at the Studio Museum know when to shock and when to hold back.

All three work reasonably familiar territory. Bethany Collins effaces, rewrites, and reproduces found text. Jenny Holzer might have produced her Colorblind Dictionary, with all references to color obscured in a real dictionary, and Glenn Ligon her scarred and blown up definition of "ravel" or "skin." Charles Gaines has erased single letters, and Allen Ruppersberg has blocked out whole passages, as in her copies of Southern Review. Kevin Beasley comes at a time of rediscovery of craft in the form of fabric, as with Barbara Chase-Riboud, and Beasley's stains and folds recall black artists from Al Loving to Shinique Smith. And Abigail DeVille enters a line of junk dealers like Isa Genzken too long to count.

Yet each also brings personal materials and personal histories. Collins wields a mean but delicate knife in cutting through paper, because skin can stand for either a covering or a painful stripping away. Like Geraldine Ondrizek in "Twisted Data," she also leaves implicit its role as a marker of race while rendering it in white. Beasley scavenges simple materials associated with creature comforts, like a pillow or a dressing gown. Then he adds a grisly reminder of the body, not unlike David Altmejd, by caking them in polyurethane and colored dust, while leaving their human scale intact. A pillowcase floats against a wall like an angel.

DeVille claims the deepest history, with titles like Gone Forever and Ever Present. She describes her assemblages as "detritus" of the Great Migration, or long African American journey north, and as "embedded histories" of entire communities. At the same time, they look quite at home on 125th Street. A black column rises, with a woman's leg showing off and peeking out. More mannequins and shopping carts, plus box springs, tumble off a gallery wall. If one has any doubt that they suggest drudgery or homelessness in the present, she also creates a Harlem Flag of fabric and sharp colors layered over slashed sheetrock. A coil of barbed wire resembles a crown of thorns.

Not everyone can say something new—assuming that, after Modernism, anyone can. The Studio Museum may well have something of a house style by now, with objects as records of historical consciousness and urban unrest. One can see it in the titles of residencies for other years such as "Evidence of Accumulation," "Quid Pro Quo," "Usable Pasts," "Scratch," "Tenses," and "(Never) as I Was." I could do with a bit less accumulation, but the program still has its purpose. It actually reduces the pressure to pounce on the new. And then it lets new artists see what develops.

Big shows of emerging artists keep coming. Two of the artists here appeared in "Fore" at the Studio Museum in 2013, one in "The Ungovernables" at the New Museum, and one also in "Starfall," a show about southern history. Yet a residency allows them a space apart from the latest thing. Beasley's dressing gown has the outline of a leaf as well as a person, as both fallen and alive. When Collins turns to painting, letters cluster and scatter like dandelion puffs in the wind. All three can decide for themselves how much to outgrow material histories.

Making progress

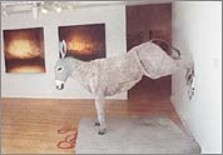

Eric Wesley is one stubborn artist. At the Studio Museum in 2001, he supplied the very image of rebellion: for "Freestyle," the first in the museum's five-year roundups of emerging artists, he contributed a mock donkey, its rear legs kicking up against the gallery wall. This being the art world, the wall did not easily give. Still, Kicking Ass was a breakthrough. The creature had thrown its tether to the ground, and its hooves could have been targeting you.

Now an artist who thrives on oversized contraptions, as in the 2004 Whitney Biennial, is turning to good old painting, in two dimensions. Much of it even looks like grass and earth. And an artist who seems to live entirely within the space of pop culture is now describing his personal life. Is Wesley learning to relax? Do not count on it, not even in his leisure time. He calls the work his "Daily Progress Status Reports."

Now an artist who thrives on oversized contraptions, as in the 2004 Whitney Biennial, is turning to good old painting, in two dimensions. Much of it even looks like grass and earth. And an artist who seems to live entirely within the space of pop culture is now describing his personal life. Is Wesley learning to relax? Do not count on it, not even in his leisure time. He calls the work his "Daily Progress Status Reports."

For starters, he mocks the very idea of progress. These days, efficient markets attain their aims through layoffs and low wages. Once, though, "Taylorism" boasted of tracking a worker's every movement and every minute of the workday. Wesley bases his series on a blank form that makes time sheets look downright lax in their oversight. Then he adds his own hourly commentary and painterly embellishment. It may take a moment to realize that he is describing not a 1950s office but home. He savages demands for workplace efficiency while applying them savagely to himself.

In a 2007 interview, Wesley called himself lazy and stupid but very productive, and the variations on a theme add up fast. Some take the theme literally, like a handwritten "wake up early." One sheet, viewed from behind with a corner turned, carries literalism to the point of trompe l'oeil. Another displays an empty suit, but of armor, looking more confining than protective. Others develop stains or an entire mottled landscape, and one can imagine a suburbanite struggling to keep up appearances. Wesley marks the occasion, perhaps bitterly, as Labor Day.

If he delights in nose thumbing, he did after all study with Paul McCarthy. Still, he is not above self-deprecation or sharing the joke with you. The variations look back with a wary nostalgia. The use of silkscreens recalls Andy Warhol and suburbia an old middle-class ideal. The series may question the possibility of African American success, whether in creature comforts or in art, while succeeding as both. It is still kicking ass.

In the back room a white artist, Scott King, is more determined in his irony. He projects the certainty of political art at its most earnest, with photographs of dreary streets that could describe a war zone. King, though, is targeting seriousness in public art. A graphic novel imagines two other notably earnest British artists, Antony Gormley and Anish Kapoor, commissioned to help "regenerate" Afghanistan (and King did call an earlier display "De-Regeneration"). The photos show people in due awe of totems and King's own fantasy public monuments—gigantic party balloons hovering over streets in London and, more ominously, Spandau. They still feel heavy-handed, but try not to take them seriously.

"Speaking of People: 'Ebony,' 'Jet,' and Contemporary art" and Titus Kaphar ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through March 8, 2015, "Material Histories" through October 26, 2014. Eric Wesley and Scott King ran at Bortolami through October 4, 2014.