School Days

John Haberin New York City

Olafur Eliasson: Take Your Time

New York City Waterfalls

Olafur Eliasson lives for the moment. Lights shift and colors shift, but ever so slowly, and so do their projections on the wall. A mist may linger in suspense somewhere in the room, defying one to call it constancy or change. One's surroundings filtered through colored plastic, along with the shadows and reflections of gallery-goers, keep the installations in the present tense.

In other words, Eliasson dwells on time and space, but not on history. When he calls his exhibition "Take Your Time," he invites others to do the same. Spread across the Museum of Modern Art and P.S. 1, it could be claiming a New York minute as its own. Later in the summer, a waterfall will cascade from the Brooklyn Bridge, just celebrating its one hundred seventy-fifth birthday. Yet little else links change to the city's past. As he puts it in the title of one large light show, I See Things Only When They Move.

Stepping into P.S. 1, however, one might be returning to school. The former classrooms, like different grade-school classes, allow an escape from the pretense of high technology and metaphysics. In the right hands, they cultivate a sense of child's play, but is that enough? Eliasson is out to update a high-toned Minimalism for an era of museum blockbusters and mass entertainment, without simply landing on either side of the equation.

His New York City Waterfalls rose four day's before the retrospective's closing. A second part of this article completes the story with the artist's latest gallery shows, two years apart. They allow him a kind of temporary escape from the masses.

Interdisciplinary studies

I never attended a gabled, red-brick schoolhouse like P.S. 1, but I like to imagine that I had. When P.S. 1 opened as galleries, one entered through steps meant for children with their book bags. Even after it merged with MoMA in 1999 and acquired a modern courtyard entrance, one had at first to navigate the old hallways and stairwells. One had to wonder, though, about its status as an alternative space. Now that management is forcing out its founder, Alanna Heiss, one has to wonder that much more.

The rude mechanics of "Take Your Time" will have to do as a chance to look back. Eliasson himself turned forty barely a year before the opening. To pull his ideas apart, it helps to return to school.

In the center of a third-floor wing at P.S. 1, for the retrospective's title work, visitors lie on the hardwood floor. They could be stretching out before a workout or just taking a rest. They are also enjoying each other and their oblique reflection in huge, rotating circular mirror, just slightly askew from the ceiling. That would be phys ed and afternoon recess. Down in the basement, one can step through or peek one's head through a wall of mist. That must be the gym shower—in anticipation of the coming swimming pool by Leandro Erlich.

Smaller rooms have a myriad of lamps and other irregular constructions of steel and glass. They put the artist's tinkering on display, as trial runs for bigger pieces to come. That would be shop class. Other rooms collect landscape photographs from his native Denmark and Iceland. The austere series of caves, glaciers, islands, and bare horizon lines purport to reveal the inspiration for Eliasson's contemplations of gallery and museum interiors. That would be social studies.

How about science class? Still other prints translate the full range of visible light into electromagnetic waveforms. For lab, one has still another programmed light box, but the honors class takes up the two-story mezzanine. In Reverse Waterfall, a sequence of small jets pumps water upward in steps, from one level to the next. It does not truly resemble a waterfall, not even when a hose at the top returns water to earth. But, hey, this is a grade-school water fountain, not a fantasy from a Renaissance or Baroque estate—or the Manhattan waterfront.

If you recognize the school day from your own life, you will understand the artist's interdisciplinary playroom. One can practically hear the bell to change class. It stages real time and real space, as filtered through real, simple, and obvious materials. The simplest work of all projects a circle of light across the intersection of a mirror and the floor, so that multiple circles appear in full. So what if one perceives only images and, more often than not, illusions?

Pomp and circumstances

MoMA has the most impressive work in "Take Your Time," if only in the sense of the most extravagant. A cheap electric fan, suspended by a long cable from the atrium ceiling, sweeps out unpredictable and very threatening arcs. It makes one aware of the room's preposterous dimensions and one's own presence. Whatever goes into the combination of a motor and a simple pendulum, its workings are entirely visible but not quite intelligible.

That description could apply to everything he does. Elsewhere at MoMA, the regular flicker of a halogen lamp congeals a cubic meter of light. A strobe light picks out a single droplet, but only because condensation and the laws of gravity ensure that the drops perpetually fall away while others take their place. It emphasizes materials, presence, and yet just enough mystification. It crosses art and science in light, quite as much as Jessica Bronson or Anthony McCall, and it does not mind if the result is more entertaining than enlightening.

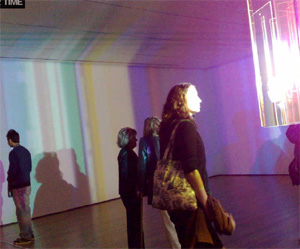

MoMA also has the room for shifting panels of colored light, interrupted by visitor shadows. It has lights that appear to change hue as one looks at them, from white to yellow to black. Other lights identify the entire spectrum with a complete rotation through a room. Toss in a kaleidoscope of mirrored "quasi-bricks," a thick wall of reindeer moss, and an alcove hall of mirrors for just one viewer over the sculpture garden, and one has an extravagant display.

Reference points pile up quickly, even beyond new media and real-time data. The emphasis on hardware as art object relate to Minimalism, and so does the invitation to contemplate one's surroundings. Do not expect, however, ready-made lighting fixtures by Dan Flavin or the transcendence of James Turrell, with his ceiling of light upstairs at P.S. 1. One can enter the work, as with Minimalism, and at times even manipulate it. Do not expect, however, to become truly a part of it, rather than an audience for prepackaged images.

The tinker-toys have much in common with gadgetry by Tim Hawkinson or David Ellis—increasingly a subgenre to itself—but without the clutter or the nostalgia for the handmade. He approaches the ingenuity of Peter Fischli and David Weiss, but not their godlike defiance of logic or their determination to trash the joint. He has the spareness and Nordic roots of Roni Horn or Rita Lundqvist, but not their naturalism, introversion, and translucent textures. The repertory of mirrors and lighted enclosures goes back to Yoyoi Kusama, who also has had museum-goers wait on line to enter a work one by one. as in the 2004 Whitney Biennial. It does not have her psychedelic patterns and the naive wonderment of the 1960s.

MoMA adds one more to the parade of huge museum spectacles by rising celebrities—after Matthew Barney, Piotr Uklanski, Cai Guo-Qiang, and Takashi Murakami, for just a few. Unlike their entertainments, however, Eliasson does not pander as much to a passive spectator or dwell on the artist's mammoth ego. He still explores art in conjunction with the viewer, and he embraces points of reference that dove more deeply into the conjunction in the past. In the end, his interdisciplinary flair makes him worthwhile, even as he skims way too quickly over one discipline after another, in search of the uninspired awesome.

The rising falls

One can tell just a little about most art by seeing it installed. Perhaps only Louise Lawler would even try. Then again, she has not pictured art the size of a waterfall. Olafur Eliasson has, and for more than three months New Yorkers could as well.

Lawler has gone behind closed doors to photograph paintings leaning against the walls and floor. She aims to demystify art and exhibitions, by calling attention to the places and choices behind them. She aims to demystify galleries and museums, too, by showing them at their least mystical. And it would never work half so well if she did not have such an eye for the art's familiarity and beauty—as image and, suddenly, as found object. Yet it would not work either if one were not so used to the dull clutter of packages half unwrapped and rooms half furnished. The French still call an opening a vernissage, a varnishing, but these days art objects look pretty much the same with and without an exhibition's veneer.

Arguably, the mainstream right now comes straight out of Lawler's playbook. Her insights into power and institutions have become business as usual. The 2008 Whitney Biennial could well have been restaging her photographs, and shows like "Undone" and "Unmonumental" could supply their title. Most overblown installations might as well have quit halfway through anyway. Yet the rules change entirely for public art. Whereas the shows I have just mentioned emphasize the public nature of an enclosed space, good outdoor installations always make one aware of one's personal involvement in a familiar but ever-changing cityscape.

Now Eliasson is erecting his four waterfalls on the East River. He always commands an illusion on a large scale, with highly visible machinery for achieving the effect. It has become a reviewer's cliché to call the mechanisms obvious as well, although often only a science student—or critic with a press handout—would think so. Seeing the scaffolding rise, however, quite literally lays them bare, along with their surroundings. One might spot their required testing as well before their formal opening, in conjunction with New York's healthy habit of summer sculpture. One might look first, though, at their underpinnings, before all that water washes the varnish away.

This time the device is obvious. Even without seeing through the work, one could predict that the Danish artist would pump water up and let gravity take things from there—much as electric pumps and rooftop water towers supply New York apartment dwellers. New York City's land masses determine the rest. The tallest scaffolding rises more than a hundred feet, about a quarter mile north of the Williamsburg Bridge, where the sanitation department's pier extends a fair distance from the Manhattan side. Another fits snugly under the eastern pier of the Brooklyn Bridge, the sole lower East River bridge support that rests on land. Others adjust somewhat in height and width for Brooklyn Heights and Governors Island, just south of the ferry to and from the Battery.

The transparency extends to a scaffold's open metal frame, to the mundane sight of one, and to the chances to view it. Many New Yorkers are sick of walking under sidewalk sheds, but they will have a special fondness for all four sites. Jogging along the East River provided a perfect way to check them out, just as it dared me to keep up with Robert Smithson's Floating Island two years ago. The construction also says a great deal about the work's place in outdoor sculpture's public-private partnership. As The Gates rose over the course of many weeks, one could better anticipate the transformation of Central Park, the minimal materials, and the collaboration between artist and volunteers that is very much a part of Christo's undertakings. Eliasson paints more in single, large, anonymous strokes, and the installation already has me thinking about what that means.

Sublime New York

I wanted, then, to review a work I had not seen—and I had all but seen it. I wanted to take one behind New York City Waterfalls and to lay bare its construction, but Eliasson does that quite well, thank you. When I described his mammoth East River project just now, before its formal opening, I wanted to connect it to the everyday sites and rhythms of pedestrians, but he handles that quite well, too. Initially, Eliasson refused to illuminate his artificial waterfalls at night. He considered it unnatural. As if nature ever had a say when it comes to New York.

The torrents cascading into the harbor for three months tempt anyone to superlatives. Who can resist repeating the facts and figures? Think of scaffolding totaling over four hundred feet in height and up to eighty feet wide, over two million gallons of water each hour, the length of plumbing risers, the environmental impacts averted, the number of fish thus saved, the people who would never have gone to Governors Island on a dare, or the $15 million in support of all this. For all that, the work's major feat is its modesty. When the flow began, I expected a transformation akin to the bright orange fabric of The Gates unfurling above their metal supports. Instead, the architecture demands equal time, and one hardly knows whether to call it a waterfall.

The torrents cascading into the harbor for three months tempt anyone to superlatives. Who can resist repeating the facts and figures? Think of scaffolding totaling over four hundred feet in height and up to eighty feet wide, over two million gallons of water each hour, the length of plumbing risers, the environmental impacts averted, the number of fish thus saved, the people who would never have gone to Governors Island on a dare, or the $15 million in support of all this. For all that, the work's major feat is its modesty. When the flow began, I expected a transformation akin to the bright orange fabric of The Gates unfurling above their metal supports. Instead, the architecture demands equal time, and one hardly knows whether to call it a waterfall.

The four installations certainly start like waterfalls—although, as Roberta Smith observes, they function more as gigantic public fountains, an artistic tradition in its own right. As they come on each day, pipes take a few minutes to start spewing water across the entire width. They direct it forward, much as a river propels itself over a cliff. After a comfortable arc, the stream drops increasingly toward the vertical. The exact shape depends on weather conditions and varies from site to site as well. The falls nestled under the Brooklyn Bridge, say, have more shelter from the wind.

Water never dissolves into an image of the sublime. The broad arc away from the vertical leaves each metal tower all the more evident. In close-ups, the water looks more like a dense wall and more a part of its surroundings, but only an intrepid boater with a zoom lens could come anywhere near such a view. The sanitation department's off-limits Manhattan wharf, the depressing lines for the Governors Island ferry, and the stone of the bridge bar too close an approach and too obvious a view. One comes closest in the Port Authority yard under the Brooklyn Heights promenade, close enough at times to feel the mist, but still only within maybe sixty yards—and only to see the water projecting off the scaffolding from behind.

The convergence of object and spectacle has mattered to art at least since geometry merged with "action painting." Eliasson likes to make a point, too, of how he pulls off his entertainments. Usually, though, he still prefers to dwell on amazement for its own sake, maybe a little too much. Here the distant views and surrounding skyscrapers diminish the work, in a good sense, and one cannot help comparing the white wall off Governors Island to the cooling tower for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, on almost the same scale nearby. One cannot help looking past the curtains of water to the frame. The magician has agreed to pull aside the curtains.

New York always offers an uncanny transposition of the Romantic sublime, which Kant defined as esthetic comprehension surpassing rational appreciation. The New York School in painting brought Kant down to human terms in its own way. On the Brooklyn side, I kept focusing on the zigzag of service stairs at the framework's center—like a fire escape of sixteen short stories. New Yorkers still escape the summer heat on structures like that, just as so many vintage photographs show kids running through jets of water from fire hydrants. One can see why they have to keep this shower behind a fence and security guard. As I turned away, I noticed a fire hydrant near the fence, its newfangled security cap firmly in place.

Olafur Eliasson's "Take Your Time" ran at The Museum of Modern Art and P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center through June 30, 2008. His "New York City Waterfalls" opened June 26 and flowed through October 14, commissioned by the Public Art Fund. A second part of this article continues the story to an exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar, concurrent with the retrospective's early weeks, and to an appearance there two years before. Louise Lawler's photographs appeared at Metro Pictures through June 7.